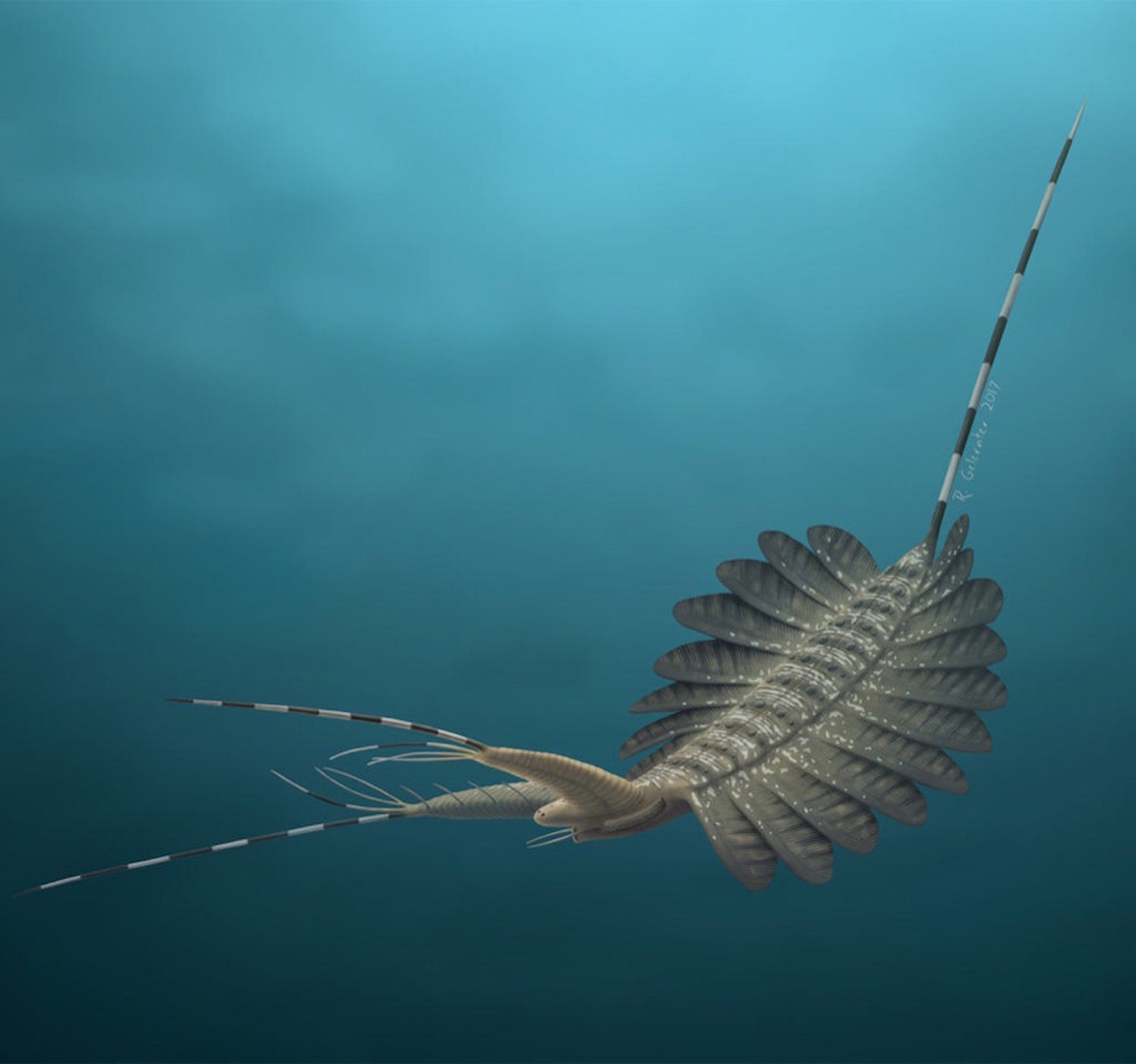

The creature in question, Kerygmachela kierkegaardi - a bizarre, oval-shaped water beast that had two long appendages on its head, 11 swimming flaps on each side and a skinny tail - isn't new to science, but its brain is, said study co-lead researcher Jakob Vinther, a United Kingdom-based paleontologist.

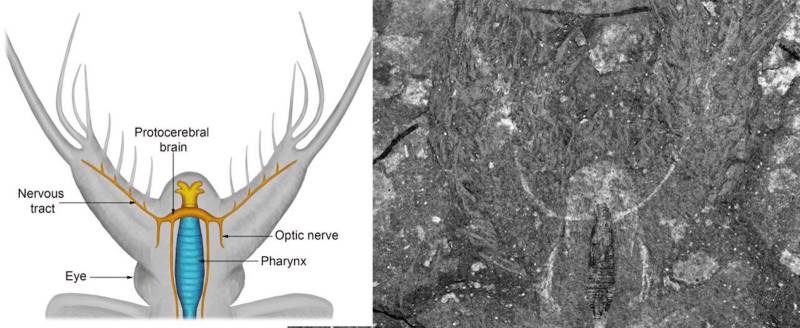

The animal would have been up to 10 inches (25 centimeters) long, based on the findings. And unlike the human brain, which is divided into three segments, the fossilized brain of this predator was simple, with just a single segment. This means that the brain was less complex than the three-segmented brains seen in the creature's distant, arthropod relatives, such as spiders, lobsters and butterflies, Vinther said.

This one-segmented brain finding is significant, and not just because it's one of the oldest fossilized brains on record. Until now, many researchers thought that the common ancestor of all vertebrates and arthropods had a three-segmented brain, Vinther said. But K. kierkegaardi's simple brainshows that this is not the case.

Despite its simplicity, K. kierkegaardi's brain helped the predator survive during the Cambrian explosion, an event that began more than 540 million years ago when a burst of life emerged on Earth. The now-extinct creature used its 11 pairs of flaps to swim through the water, hunting for prey. An anatomical analysis showed that K. kierkegaardi's brain innervated the creature's large eyes and the frontal appendages it used to grasp its tasty victims, the researchers said.

"[Its eyes] form an intermediate step between more-simple eyes in [modern] distant relatives, such as velvet worms and water bears [also called tardigrades], and the very, very complex eyes of arthropods," which sometimes sit on the end of eyestalks, Vinther said.

The study was published online March 9 in the journal Nature Communications.

Laura Geggel is a senior writer for Live Science covering general science, including the environment and amazing animals. She has written for The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site covering autism research. Laura grew up in Seattle and studied English literature and psychology at Washington University in St. Louis before completing her graduate degree in science writing at NYU. When not writing, you'll find Laura playing Ultimate Frisbee. Follow Laura on Google+.

Reader Comments