"I just heard the funniest joke in the world!"

"Well, go ahead, tell me!" says the other judge.

"I can't. I just gave someone ten years for it."

With the fall of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the world lost one of humanity's greatest cultural productions: the communist joke. Crossing cultures and borders, the jokes were unique, ubiquitous, and jam-packed with information. They were funny too. The mix of totalitarian power, propaganda, censorship, and ineptitude created the perfect climate for an underground joke-telling tradition.

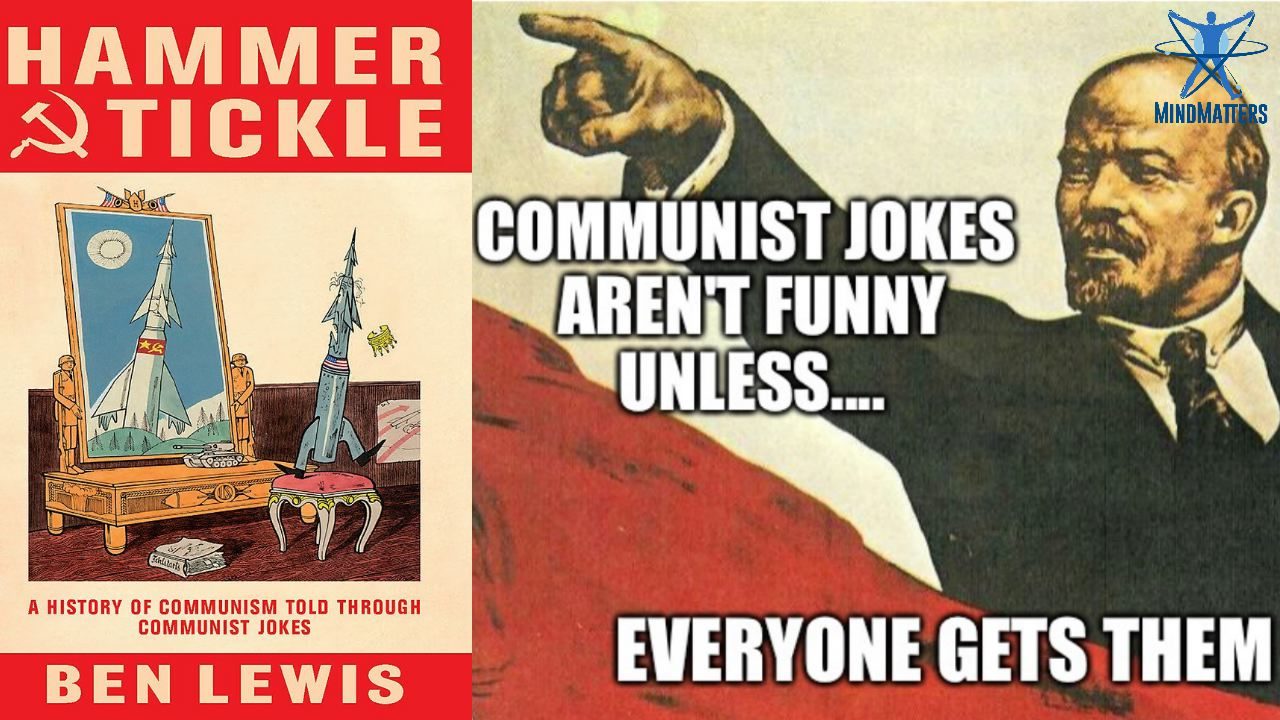

In his book, Hammer and Tickle, Ben Lewis tracks down all the best jokes from the era, providing not only a handy compendium, but a cultural history of communism in the process. As communism changed, so did the jokes, revealing the different experiences and attitudes of the people during the times of Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev, and then into the stagnation of the Brezhnev years and finally the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Note, MindMatters will be back in January. Merry Christmas, everyone!

Running Time: 01:22:14

Download: MP3 — 107 MB

Other media mentioned in the show:

- Political Ponerology

- In the First Circle

- MindMatters: The Truth About Doublespeak and the Antifa Handbook

Harrison: So, one Soviet citizen says to the other, "I want to sign up for the wedding list for a car. How long is it?" Response: "Precisely 10 years from today." "Morning or evening?" "Why what difference does it make?" "Well the plumber's due in the morning."

Elan: Ha ha. {laughter}

Harrison: That is one of many of a type of joke that you don't see anymore and that is the rich reservoir of communist jokes from the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc countries, kindly compiled by Ben Lewis in his book Hammer and Tickle, the Story of Communism, A Political System Almost Laughed Out of Existence. It was also made into a documentary I believe. I haven't seen the film but the book is quite in-depth. This guy had an obsession with jokes and communist humour and not only collected as many books in as many languages as possible that he could find, from small presses in all kinds of countries and languages, went to all these countries to talk to people and record all of the jokes because this was a big thing in the Soviet Union right from the beginning and went through some phases as the phases of that system progressed throughout the years.

But it created this body of jokes that was unique. He argues it was unique in the wider field of joke study, jokology-I don't know what it is. But then when communism fell in those countries it went away. There's still political humour but there was something about the communist jokes that made them particularly resonant at the time and among the peoples in these various countries.

So we're going to be talking a bit about that, a bit about the context and mostly just telling a lot of jokes, hopefully, because some of them are quite funny. Not having been raised in such a country, I guess with some of the jokes you kind of had to have been there in order to really get them, but I think they're pretty clear and you can get an idea of why the joke is funny without too much explanation.

Carolyn: Yes, he writes regretfully that so many had to be left out because they were partly based on puns, on local slang, but this idea of being able to comment without too much consequence was sort of the currency of that particular aspect of the culture.

Elan: And why even have as a subject of our show today the jokes of Soviet culture? The reason is, I think in part, that the jokes reflect a very deep disquiet and a sense of helplessness that most people had to do anything else but joke about a system that kept them so oppressed, so subjugated, so lacking in basic services, so deficient in any kind of humanity for so many decades. So this was a healthy outlet for many of the people, not only in Russia but in the Soviet bloc. Lewis gets into that a little bit in his book. He discusses the fact that a lot of these jokes are common to Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and a number of other countries that were in the sphere of Russia and the Soviet Union. They were part of this whole system that had influenced the thinking and the empowerment of the communist party, as we've come to know it.

So there's a lot of insight into how people were dealing psychologically and emotionally with the political system as it was.

Carolyn: It was a way of standing in the face of having to affirm the exact opposite of what was right in front of your eyes, that you had to stand there and say, "Oh yeah, everything's fine. Production is perfect. Crops are great."

Harrison: Yeah. A couple of different things. One, he points out that he thinks the reason for this particular type of humour and the reason that it existed, or at least part of the reason, had to do with the nature of the communist system. There were three features that led to it. I'll see if I can remember them. One was the absolute ubiquity of communist propaganda. Everywhere you turned, whether it was the newspapers or billboards, you were constantly bombarded with the propaganda. So of course every normal person could see the disparity between the propaganda and the reality so there was that automatic disconnect, just because it was everywhere and so obvious and in your face. But then there was the fact that the government was this totalitarian dictatorship so you couldn't stand up on a street corner and tell the truth because chances are you'd be arrested. I forget what the third one is, but I'll find it eventually.

Just to give an idea of what this was like, in the introduction he gives some background information, some people he knew and talked to, some friends of his. I'll start with another joke. He's talking to one of his Romanian friends and they relate these couple of jokes. Why, went another Romanian communist joke, did Ceaușescu hold a mass rally on the first of May? To see how many people had survived the winter. Another one: Do you know when the foundations of the Romanian economy were laid? As far back as biblical times. Jesus was put on the cross. They asked him to stretch out each hand and knocked a nail in. Then they said, 'Please cross your legs. We only have one nail left.'

His friend was this lady Doyena and she insisted that joke telling was dangerous. You could go to prison for it and she points out some examples. She was a copy editor at the Daily Gazetta and there were certain problems that you would run into because, as in most languages, with certain words, if you change one letter you get a different word. So Ceaușescu's first name was Nicolae and if just changed a couple of letters and changed the spelling of it, Nicolae means small penis in Romanian. {laughter} So she had to be extra careful to make sure Nicolae was spelled correctly every time because otherwise you might be calling him small penis Ceaușescu {laughter} and that wouldn't go over very well.

There was another one, the word comrade. Several months ago we did a show on communist propaganda and talked about the researchers - I think they may have been Czech - who did a study of word usage in the propaganda pieces. So they took all of the newspapers and pamphlets and did a word analysis to find out which were the most used words. And of course comrade was up there as one of the top ones. But in Romanian, if you change one letter in comrade you get 'wicked convict'. So if you're talking about your comrades and you accidently call them wicked convicts, that would be a bad thing.

One morning she had accidentally done this. I'll read what happened.

"One morning when I went to work my editor told me that I had to go to the comrade in room such-and-such, which was how they referred to the Securitat officer. I said, 'My goodness, what did I do?' And he said, 'Look on the front page. You misspelled the word comrade.' I was questioned for several hours about this mistake. They asked me if I supported the party and they interrogated all of my colleagues. Did I ever say anything critical about the government or Ceaușescu? My only defense was, you know, I signed off the proof of this newspaper. If I wanted to undermine something or to fight against our illustrious President, I wouldn't have been so stupid as to sign it. But it took me more than four or five hours to convince them."

One of the points he makes is that in certain time periods, in the Soviet Union for instance, you could go to jail and you did go to jail for telling jokes. then with Khrushchev it got a bit easier. You wouldn't necessarily be arrested. Then it got to the point where you could pretty much openly tell jokes for the last 10 or 20 years of the Soviet Union. So it liberalized the joke telling climate. But for a while there it was pretty hairy. You could go to prison for jokes and there are several jokes about going to prison for jokes.

There was another one. I'll have to paraphrase it because I don't have the page number off the top of my head. This was a common joke and it was actually used in a trial. I can't remember which country it was. It might have been Romania. A comedian, a writer got arrested and at his trial they ask him, 'Where were you, what were you doing on April 3, 1963?' So he repeated the common joke, "Why comrade, I was looking at my clock at the same time that I was looking at my calendar. I remember exactly what I was doing." {laughter} That was a common question, where were you and what were you doing at this time on this day? Well, the only thing they could possibly be doing if they remembered that is looking at the calendar and the clock, right. So he actually said that at his trial and ended up going to prison for however long.

That was a small picture of the climate of joke telling at the time and in these various countries. Before going on, I'll just read a couple more.

"A man drives up to the Kremlin and parks his car outside. As he's getting out a policeman hurriedly flusters over and says, 'You can't park here! That's right under Yeltsin's window!'"

So this is a post-communist joke but the same flavour.

"So the man looks perplexed for a second then smiles and calmly replies, 'No need to worry officer. I make sure to lock the car.'" {laughter}

Alright, a couple more.

"Another conversation, one man to another. 'My wife has been going to cooking school for three years.' The other man. 'She must cook really well by now.' First man, 'No. So far they've only got as far as the bit about the 20th communist parties of the Soviet Union congress.' End of joke.

And one final one.

"A man walks into a shop and asks this: 'You wouldn't happen to have any fish would you?' The shop assistant replies, 'You've got it wrong. Ours is a butcher's shop. We don't have any meat. You're looking for the fish shop across the road. They don't have any fish.'"

{laughter}

Elan: These are obviously terrible things to laugh about, in a sense, but they manage to reveal the gallows humour, the way that these people had dealt with such situations and reveal the reality of life under communist occupation, if you want to say that, for so long. I don't recall where in the book I'd read this but I thought it was a great passage, that these were the truths given by ordinary people, untainted by the agendas of historians, the propaganda of state agencies or the vagaries of personal memories.

So there's truth that is being communicated and transmitted through this humour that gives an account for the lives of these people, hundreds of millions of them, under extreme oppression for quite a long time. It's very difficult, I think, to get a really good sense of what life was like without these authentic, personal, gut-wrenching explanations or anecdotes. They called them anecdoti. The humour stems from a Russian tradition in humour to explain things through little anecdotes that were humorous, that came from the population, that were populist jokes, that weren't official, that claimed truth to power in a way that a newspaper article or a book or state-funded piece of literature just couldn't. So that's a great deal of the value here.

Carolyn: At one point he writes of the joke as a tool of communication being packed to the hilt with information worth more than volumes of philosophical essay, that expose the absurdity of propaganda tricks. Just to segue a little bit, even our favourite analyst of totalitarian regimes, Lobazcewski wrote a little bit about this culture of truth telling and communication through jokes.

Elan: And this is from Political Ponerology.

Carolyn: This is from Ponerology.

"Any attempt to make a society subjugated to the above phenomenon (which is this relentless barrage of propaganda) learned this differential experiential manner imposed by pathological egoism is in principle fated to failure regardless of how many generations it might last. It does however call forth a series of improper psychological results which may give the pathocrats the appearance of success. However, it also provokes society to elaborate pinpointed, well thought out defense measures based on its cognitive and creative efforts. For some mysterious reason those 'others', the one that pathocrats can't subjugate, wriggle out, slither away and tell each other jokes about pathocrats. Someone must be responsible for this, the revolutionary oldsters or some radio stations abroad."

So this idea that the innate human creativity of the normal person will not be forever oppressed. It will find its way out one way or another and if nothing else, it's always going to the back room in someone's house or down in the basement and drinking vodka and telling jokes.

Harrison: I want to read a couple more quotes from Ponerology because there's only a few points in the book that he mentions humour but I think it's a really important aspect of it. The first one goes like this,

"Societies governed by a pathocratic system for many years develop the above-described natural immunization (that's an immunization to the mind-numbing, soul-destroying routine and oppressive atmosphere of living in this kind of society ruled by psychopaths at every level) along with the characteristic detachment from the phenomenon and sardonic humour. In combination with the growth of practical knowledge, this state should be taken into account every time we wish to evaluate a given country's political situation. We should also underscore that this immunity refers to the pathological phenomenon per se, not its ideology, which explains why it is also effective against any other pathocracy, no matter the ideological mask. The psychological experience gained permits the same phenomenon to be recognized according to its actual properties. The ideology is treated in accordance with its true role."

So he just kind of embeds the reference to humour in this wider analysis of the nature of pathocracy which exists in its essential form regardless of the ideological garment that it's wearing at the moment. So you can find the same phenomenon, whether it's the Soviet Union or some other pathocracy that's not under a Marxist/communist ideology.

Then the other one went like this,

"The development of familiarity with the phenomenon (pathocracy) is accompanied by development of communicative language by means of which society can stay informed and issue warnings of danger. A third language thus appears alongside the ideological doubletalk described above. In part, it borrows names used by the official ideology in their transformed, modified meanings. In part, this language operates with words borrowed from still more lively circulating jokes. In spite of its strangeness, this language becomes a useful means of communication and plays a part in regenerating societal links. Lo and behold, this language can be translated and communicated in relations with resident of other countries with the analogous governmental systems. Even if the other country's official ideology is different. However, in spite of efforts on the part of literati and journalists, this language remains only communicative inside. It becomes hermetic outside the scope of this phenomenon, uncomprehended by people lacking the personal experience."

So the jokes aren't themselves an example of this language. The language he's describing is more of a code talk between people living under this system that wouldn't be understandable by outsiders, essentially. But jokes make up a part of this language. You see what he's describing, the almost cross-cultural current of these jokes in all of these countries. As one of you mentioned at the top of the show, these jokes migrated. So you'd find the same jokes in Czechoslovakia or Romania or Hungary or the Soviet Union and everyone thought they were their own jokes. 'These are the best Czech jokes and these are the best Russian jokes.' Well no, no one knows who wrote them. They just flowed across these borders among these people and it was immediately recognizable. This joke-telling culture was immediately recognizable to anyone living under this system. It's really interesting when that happens.

Carolyn: So do you know what would happen if they brought in communism to Saudi Arabia?

Harrison: What?

Carolyn: It would be tragic. They would run out of sand! {laughter}

Harrison: And a variation on that is there'd be oil shortages.

Elan: Well you have to wonder if there wasn't some 100th monkey syndrome going on.

Harrison: Yeah.

Elan: Where these jokes and insights into the behaviour of the NKVD, the secret police at the time, where every country had its own version, the Stasi in East Germany and all these other countries had some correlative secret police agency. You had to wonder if there wasn't some kind of spontaneous awareness of something funny that was almost telepathically communicated, as well as transmitted verbally.

Carolyn: Well the thesis that he started out with is he wanted to prove that humour was one of the major components that brought down communism.

Elan: Right.

Carolyn: And all the way through the book he keeps slipping back and forth between what was called the minimalist position, which was the jokes were just to make life bearable and to provide a sense of comfort, and to the idea that this was a way of not precisely organizing a rebellion, but to keep the spirit alive and to augment it. The one thing he found is that the more the jokes were told, the more they circulated, even if they were only attached to the events of the day, because he runs into a guy who actually did a study on that and, honest to god, in a 10 year, one person survey, they created consensus. The further the joke travelled, that was a symbol and a sign that there was a consensus to that point of view, whatever was being expressed by the joke.

Elan: Right. You mentioned a minimalist and there's also the maximalist interpretation.

Carolyn: Which said it was essential in welding together a point of view for the majority that would eventually bring the system down.

Elan: Kind of a death of a thousand cuts...

Carolyn: Exactly.

Elan: ...that was powerful enough, through the jokes, to bring up into consciousness, a version of reality, an understanding of how things were, that were so bad that people probably in the inner circles of government couldn't deny it.

Carolyn: They had to pay attention.

Elan: They had to pay attention. It was undeniable. This actually reminds me of a passage about Stalin who I think was indicative of the worst elements of communists under this system, who would actually joke about himself, but underlying it was this psychological terror that he inflicted on people in his own inner circle that was sometimes joked about, about him, but sometimes joked about, by him.

Carolyn: Which was just a way of increasing the terror. "I can make a joke about my own evilness and you can't do anything about it."

Elan: So Lewis says,

"Stalin liked to make jokes about his power and his kindness. There's a similar binary structure to them all in which he ironically admits the violence of his rule but then supplies a punchline suggesting his magnanimity or vice-versa. Once, the opera singer Ivan Kozlovsky, the lead tenor at the Bolshoi from 1926-54 was giving one of his many private performances at the Kremlin. Members of the Politburo clambered for a particular song. Kozlovsky hesitated. Stalin said, 'Let's not put comrade Kozlovsky under pressure gentlemen. Let him sing what he wants.' He paused for a moment and continued, 'And I think he wants to sing Lenski's aria from Onegin.'"

There's just a bit more here.

"In December 1944 at the close of the war, the future French President Charles De Gaulle flew to Moscow to sign a treaty with Stalin. At a state banquet the drunken Soviet leader introduced him to the other guests, the members of the Politburo. He raised his glass to "Iron" Lazar Kaganovich whose enforcement of collectivization in the Ukraine and brutal management of Soviet railroads and heavy industry made him personally responsible for thousands of arrests, deportations and deaths by starvation and execution. 'A brave man,' Stalin said. 'He knows that if the trains do not run on time we shall shoot him!' Stalin clinked glasses with Kaganovich. He toasted the health of the quartermaster general and the Red Army, Holev, who had performed logistical miracles in the Second World War. 'He'd better do his best or he'll be hanged for it! That's the way we do things in our country.'

Stalin then looked at Novikov, the brilliant air force commander who helped turn the tide of the war at Stalingrad with innovations such as tank buster bombs, night fighters and low-level bombing. Stalin said, 'Let's drink to him and if he doesn't do his job properly, we'll hang him.' Stalin caught a look of disgust on De Gaulle's face and said to him, 'People say I'm a monster, but as you can see, I make a joke out of it. Maybe I'm not so nasty after all.' Shortly thereafter Novikov was arrested, tortured and sentenced to 15 years hard labour."

So there is a kind of reverberation of reality to the joking that was Stalin's that confirmed that he was a monster, even if he made light of it in some contexts.

Harrison: Then Lewis has some jokes that the people came up with about this very feature of Stalin. I'll read some of these.

"So Stalin is giving a speech to an assembly of workers in a big factory. 'The thing we hold most precious in the Soviet Union is a human life,' he says. Suddenly someone in the audience has a fit of coughing. 'Who is coughing?' bellows Stalin. Silence. 'Okay, call in the NKVD,' says the dictator. Stalin's political police, the NKVD, rush in with semi-automatic weapons blazing. Soon only seven men are left standing. Stalin asks again, 'Who coughed?!' One man raises his hand. 'That's a terrible cold you've got. Take my car and go to the hospital.'"

Then another one.

"A Georgian delegation has come to visit Stalin. They come, they talk with him in his study and they leave. No sooner have they disappeared down the corridor than Stalin starts looking for his pipe. He opens drawers, moves papers, but he can't find it anywhere. He shouts down the corridor for the head of his political police, Lavrentiy Beria. 'Beria,' he says, 'I've lost my pipe. Go after the Georgian delegation and see if you can find if one of them took it.' Beria bustles off down the corridor. Stalin carries on looking for his pipe. After five minutes he looks under his desk and finds it on the floor. He recalls Beria. 'It's okay,' he says, 'I found my pipe. You can let the Georgians go.' Beria replies, 'It's a little too late for that. Half the delegation admitted they took your pipe and the other half died during questioning.'"

Carolyn: Black humour at its finest.

Harrison: Yup. Maybe we'll go a little lighter on these next few jokes.

"A frightened man came to the KGB. 'My talking parrot has disappeared.' 'That's not what kind of case we handle. Go to the criminal police.' 'Excuse me, of course I know that I must go to them. I am just here to tell you officially that I disagree with that parrot.'" {laughter}

"In a prison, two inmates are comparing notes. 'What did they arrest you for,' asks the first. 'Was it a political crime or a common crime?' 'Of course it was political. I'm a plumber. They summoned me to the district party committee to fix the sewage pipes. I looked and said, 'Hey, the entire system needs to be replaced.' So they gave me seven years.'"

One more.

"What's the difference between a capitalist fairy tale and a Marxist fairy tale?"

Elan: What Harrison?

Harrison: "A capitalist fairy tale begins, 'Once upon a time there was..., a Marxist fairy tale begins Some day there will be...'" {laughter]

So do you guys have any more?

Elan: Well I was thinking about this book by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn In the First Circle, which is a harrowing discussion - I'm going to hold this up for a second longer in case anyone wants to look at it. It's a wonderful novel, but again, quite harrowing. It follows the lives of scientists and workers and engineers in a work camp who were under pressure to build certain technologies that would help the government. They were doing this for many years. So instead of a gulag where they might be sent for 20 years for some form of subversion which was quite often arbitrary or mild, because so many millions of individuals were sent to these work camps and gulags in Siberia and various other places where conditions were horrible.

So this was, by comparison, kind of a luxurious place to serve out your sentence if you were willing to spend 10 or 12 hours a day working on technology for the state. We've done a show on Solzhenitsyn's warning to the west. He was so filled with insights and he had a number of insights about Stalin and actually, in spite of the rather disturbing descriptions of the reasons why so many of these individuals were put in this prison and sent away for so long, the book is very funny in many places. The characters' humour comes out in all sorts of conversations that they have with one another. Some of them in fact, are diehard communists but just think that the system needs a little more work or there's a mistake made. But they're ideologically adherent to what Lenin originally proposed and Trotsky perhaps.

So you get those points of view but you also get a lot of insights about the system itself as it existed and some about Stalin himself. There are a few scenes that follow Stalin around in his antechamber, smoking his pipe, reflecting on things, terrorizing the generals that are in charge of force-working these individuals into creating technology and how this reign of terror works from the top down. So it's very insightful. I'll read this passage.

"Stalin had not trusted his own mother, not god, not his revolutionary comrades, not the peasants. You couldn't trust them to sow and get the harvest in unless you forced them, not the workers who wouldn't work unless norms were set for them. Still less did he trust his engineers. He had not trusted his soldiers and generals to fight without punitive battalions and security detachments to cut off their retreat. He never trusted his henchmen. He had not trusted his wives and mistresses. Even his children he had not trusted and he had always been proved right! There was one man he had trusted, and only one. In a life free of trust and mistakes, in the eyes of the world, that man had seemed so firm in friendship and in enmity, he had swung around so sharply and held out his hand in friendship. This was no windbag. This was a man of action. And Stalin had believed him. That man was Adolph Hitler. Stalin had looked on with approval and malicious glee while Hitler dismembered Poland, France, Belgium, while his planes blackened the skies over England.

Molotov came back from Berlin in a fright. There were intelligence reports that Hitler was concentrating troops in the east. Hess fled to England. Churchill warned Stalin that he was about to be attacked. Every rock on the aspens of Belorussia and the poplars of Galicia screeched warnings of war. Every market woman in Stalin's own country prophesied war from one day to the next. Stalin alone was unperturbed. He went on sending train loads of raw materials to Germany and did nothing to fortify his frontiers for fear of offending his colleague.'"

It's kind of funny in a way. He doesn't trust anybody. No one. Not a soul. Not even his own mother, except for Adolph Hitler! {laughter} Which in Solzhenitsyn's quite literate way, gives you some great insight into Stalin's lack of insight. The book is filled with a lot of these observations that are quite pithy and good.

Carolyn: One more thing about the jokes before I guess we're moving on to the modern day iteration of the political joke...

Harrison: I still have some jokes.

Carolyn: You still have some jokes? Oh well, we'll have to hear them. But later on in the book in a wonderful chapter called The End is Wry because he is tracing the evolution of the joke as communism edges towards its end, he talks about the fact that, especially in Poland, the elite start to catch on and weaponize jokes themselves. That sort of spoke to me, that you had to have a certain minimal allotment of intelligence for a joke to be effective on you. He talks about going to see Lech Wałęsa who he found humorless. He had not sense of humour at all. He was not very intelligent, not very flexible. It was a complete disappointment because he wanted to talk to him about jokes and the thing is that for 10 years I think, the Polish government had hired a satirist who had absolutely no loyalty to anybody. He had been on the side or the opposition and then he got offered a really good job so he started writing jokes about Solidarity and Wałęsa.

But it's like they finally caught on that this is something that they could use too. But this guy wrote for everybody. He ran a Polish equivalent of Private Eye, which is this nasty, vicious political satire magazine in Britain. Apparently his version of it was immeasurably more nasty. But in the end there was still this understanding that even though this guy was witty and urbane and making loads of jokes, it didn't catch on the way it did with the common people behind Solidarity.

I guess you have to keep your guard up because even humour can be turned against you if you're not alert enough. More jokes.

Harrison: So Stalin is in his limo along with his driver. "Let me ask you a question" he asks the chauffeur. "Tell me honestly, have you become more or less happy since the revolution?" "In truth, less happy," says the driver. "Why is that," asks Stalin, his hackles raised. "Well before the revolution I had two suits. Now I only have one." "You should be pleased," says Stalin. "Don't you know that in Africa they run around completely naked?" "Really?" the chauffeur replies. So how long ago did they have their revolution?" {laughter}

Okay. What is the definition of capitalism?

Elan: What?

Harrison: The exploitation of man by man. And what is the definition of communism?

Elan: The exact opposite. {laughter}

Carolyn: Orwell would be proud.

Harrison: Trotsky wakes up in the morning. "How are you?" an assistant asks. "I don't know," he says. "I haven't read the papers yet." Okay, let's see here. I'm just going to go through all my favourites.

"Stalin dies and he's not certain whether he wants to go to heaven or to hell. He asks for a tour of each. In heaven he sees people engaged in quiet prayers and meditation. In hell people are eating, drinking, dancing and generally having a good time. Stalin opts for hell. He is led through a series of labyrinths into an area with boiling cauldrons. Several devils grab him. Stalin begins to protest and points out that on his tour he was shown people enjoying themselves, "That," replies the devil, "was just propaganda." {laughter}

Elan: That's one of my favourites too. I love that one.

Harrison: Okay.

"Somewhere in Siberia, three prisoners are sitting together and they finally get to talking about why they were deported. 'I'm here because I always arrived at the factory five minutes late so they charged me with sabotage,' says the first. 'That's strange,' says the second. 'I'm here because I always arrived at work five minutes early, so they convicted me of spying.' 'No,' says the third in surprise. 'I'm here because I kept arriving at the factory on time, every day and then they found out that I owned a western watch.'" {laughter}

A couple more from the Stalin era.

"Two gulag inmates are talking about why they got put away. (This was a big theme, the gulag jokes.) 'I'm here for laziness,' says one. 'What do you mean? Did you fail to turn up for work?' ask the other. 'No. I was sitting with a friend telling jokes all night and I thought, at the end I'll go to bed. I can report him to the police in the morning.' 'And why was that lazy?' 'He did it in the same evening.' {laughter}

"A new convict arrived at a prison camp. The inmates began questioning him about the length of his sentence. '25 years' replied the newcomer. 'What for?' 'Nothing. Didn't do a thing. I am innocent.' 'Don't give us that story! The innocent only get five years!'" {laughter}

Elan: Yeah!

Harrison:

"What's the difference between Stalin and Roosevelt? Roosevelt collects the jokes that people tell about him and Stalin collects the people who tell jokes about him." {laughter}

Carolyn: Actually, there's something interesting about that. Reagan was a huge fan of communist jokes and he wanted them included in his briefings every day. If there had been a new joke he wanted to hear about it and he started weaving them into all of his addresses. This was during the whole time. At press conferences, speeches, whatever he was doing, there was some joke about communism and a lot of people figure his ridicule as much as anything else, showed his support for the people. But apparently he's a big fan and there's a huge collection of them somewhere in his library.

Elan: Well just looking back at President Reagan in the 1980s, I hated the guy. I so disliked him, I thought he was one of the worst representations of what a president should be for various reasons. And at the same time you say that Carolyn, he in the end got together with Gorbachev and had some very successful meetings with him, even if the George Bush administration turned around and reneged on their promises not to encroach on Russia with NATO in later years.

In any case, he seemed to be an honest broker. You have to wonder if maybe Reagan, underneath this idiotic veneer of fake presidential puppetry, was trying his best and had some kind of healthy outlook! He really believed that Russia wasn't an evil empire and I think that when it came down to it, he was sincere about détente and establishing good ties with Russia.

Carolyn: Well you could sort of look on him as - maybe this isn't the right term - but kind of a low rent Khrushchev and JFK. Neither of them had the intellect that the other two had, but I think they were sincere. I've heard some anecdotes about Reagan, that at least on a personal level he was a relatively decent person. He had his own ideological possession but I think as much as he hated communist Soviet Union and wanted to bring it down, I think that it was something he wanted to accomplish without a war, without destruction and that was Gorbachev's goal too.

He talks a bit about Gorbachev in the book, who looked around and said, "This is a disaster! We're going to hit the wall," just in terms of their GDP and production and state of the citizenry and the state of their infrastructure and he knew that something had to be done fast. So that also led to the opening, whether or not you want to blame that on Reagan forcing the arms race and forcing Russia to spend itself into the ground or the Soviet Union, actually, is moot. It was tottering under its own contradictions.

Elan: Yes.

Carolyn: But there seemed to be this will to try and do it in the least damaging fashion possible. But that doesn't make a lot of money for the warmongers, so you can't have that.

Harrison: Well one interesting thing I found out about these jokes is that in the early years, a lot of the joke tellers and the jokes themselves weren't anti-communist per se. A lot of the people telling the jokes were still communist. They still might be like the guys in the camp with Solzhenitsyn who were still hard core communists. They just believed things needed a bit of tweaking and maybe there was some ineptitude going on, but they still valued the ideals.

But it wasn't until the stagnating 1970s and 1980s that people finally came around to going after Lenin because Lenin wasn't the butt of jokes early on. That was mostly reserved for Stalin and then finally, eventually they realized the whole system was bad from the beginning so that's when they started joking about Lenin. So there are a few jokes about Lenin that came out around this time and they're all really good.

"School children come to visit Lenin's widow, Nadia Kruchskya. 'Granny Nadia, tell us a story about Lenin,' they ask. 'You know children about Lenin's very great kindness,' she says dewy-eyed. [language warning for this one] 'I remember once when a group of children came to visit Vladimir Ilyich while he was shaving. 'Play with us grandad Lenin,' they said. 'Fuck off you little bastards,' he told them. His eyes were so kind."

Second joke.

"When we say Lenin, we mean party. When we say party we mean Lenin. And this is how we deal with everything. We say one thing. We mean something else." {laughter}

The third one.

"And then they came out with a bed that sleeps three because, like the slogan says, Lenin is always with us." {laughter}

Very good stuff. I've almost gone through my personal catalogue of my favourite jokes, but before we do that I want to share a video. This is a clip from a documentary that was done by the BBC several years ago called The Lost World of Communism. So they find this group of people in Romania that did a stand-up comedy routine. Well it was scripted. It was a live comedy show. So I think that's all the background you need for this clip. If not I'll explain some more afterwards.

Video:

Narrator: The dreadfulness of everyday life provided rich material for one student comedy group. They filmed this spoof New Year's broadcast by Romanian TV for their private amusement. But before any public performances, all their sketches had to be approved by the censors.

Performer: It reached the height of stupidity when the ministry of culture and communist education - I hope my memory's not betraying me and this was the actual name - had issued a list of forbidden words. These words weren't allowed on stage, in shows, on TV, in newspapers, anywhere else. Yes, newspapers too. So these words were forbidden.

One forbidden word was dollar. The censors assumed that anyone who used the word must be an enemy of the working class. One of the jokes was that as we couldn't say the word dollar we claimed we had bought a piece of machinery with rubles. The censors were outraged by this as well and wrote on our script, "Any other currency". And we said exactly that. We bought this piece of machinery for 300 any other currency. The audience burst into hysterical laughter. It was funnier than any other word we could have used because the student audience cottoned on to the fact that we'd been censored. The censor, a really nice guy, didn't want to impose on us the alternative to the word dollar so he allowed us to choose any other currency as long as it wasn't the dollar. But we took it literally and said it cost 300 any other currency. People roared with laughter.

Harrison: I saw that years ago and it stuck with me so when I finally got around to reading this book I remembered it because of just the absurdity of that situation. You've got this list of banned words like dollar. The total idiocy of that kind of censorship. This is the genius of the communist humour. Just flipping that around, just taking it literally makes it funny. You just replace the word with the censor's comment and you get just a golden joke. {laughter} It's funny because the censors, the people coming up with these decisions are totally humorless, right, and yet if you just take them at their word, they're actually hilarious, totally unintentionally.

Carolyn: Obliviously.

Harrison: Obliviously hilarious. That really just summed it up in one way. Then there's another clip. I can't remember if it was in the same episode because it was a three-episode documentary. But there's another one where they said because so many words were banned they just mimed the entire skit, without words. So it was about farming or something and it was also hilarious because they realized they can't say any of these words so they're just miming all the actions. That's what you had to do to get around it. These are just regular, funny, creative folks. It's hard to imagine if you haven't lived under it that something so routine and so unimportant, really, or you'd think it would be unimportant, can be banned like that.

One other point that he makes, before I get into this next point, is that this really was unique to the communist system in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. He couldn't find this kind of humour anywhere, for instance, in Cuba or China. They just didn't have the same kind of humour. There was something specific about the way the communist system was set up in the Soviet bloc countries that didn't translate to Cuba or China.

Carolyn: Well he did mention that a certain number of the oldest jokes that he could find actually arose from the 16th and 17th century peasantry who laboured under feudalism, which you could make a lot of analogies to. So maybe Korean, Chinese or Cuban peasantry didn't have that same experience. So that could have something to do with it. But within that whole geographic area, feudalism had existed in one form or another and the jokes just sort of propagated down the ages.

Harrison: So it could be partially the form of the humour is culture-specific for that area. So you wouldn't find the same humour in a different culture. Apparently in China the humour is a lot more slapstick. It's really people falling over and getting punched and things like that. So maybe there's just not the same ground out of which these kinds of jokes would grow.

But just on the issue of censorship, everyone knows about China's great firewall. But there's some equally idiotic - I think - types of censorship that go on in China because the Chinese government is notorious for that. A few years ago Xi Jinping made a visit to this local cafeteria, local restaurant and he ate a special kind of steamed bun and the word for it - I can't remember what the Chinese word for it is - kind of rhymes with his name.

So even supporters started calling him, as a cute reference, Xi-bun, the same word for bun. It was this cute thing, 'Oh Xi-bun.' One guy I guess got too carried away and got arrested for 22 months for calling Xi...

Elan: Oh no!

Harrison: ...the Xi-bun. When you have government censors like this, they just come up with the most stupid things. At least some examples of censorship, even if they're stupid you can understand why. There's a reason, that at least on the surface of it makes sense.

Carolyn: To them.

Harrison: To them, regardless of how misguided it is to actually try to censor. But there are examples of why would they even think that? You make things even harder for yourself by trying to censor this and you probably just gain a lot more resentment than you would if you just let people use somewhat ordinary words.

Elan: Well I think that's actually a good segue into another discussion and part of this whole examination of humour in a totalitarian environment because we've been observing here in the US and in Europe, a stifling of humour that's been going on for the past, I would say 10 or 20 years, and really ramped up in particular in the past few years where you're not allowed to say certain things. It would seem to me that that's a lesson learned by the totalitarian thinkers, or maybe I'm just ascribing it to them as a lesson that they learned. Maybe it's not a lesson at all.

But it seems to me that all of the kinds of astute observations of where things have been going in terms of a stronger police state in the US, Russophobia, political correctness, totalitarian leftist fascist ideology, you're not really allowed to talk about it. And so we've mostly been seeing the jokes made about these types of things through memes. I don't know about you guys, I just haven't heard any really clever jokes being told about any of this phenomenon here. Usually it's just a meme that we'll put on an article on SOTT or that we'll see on a Twitter feed or a Facebook feed that hasn't been censored, for whatever reason.

So the censorship is here already, to some great degree. I don't think there's enough humour that's correctly pointing out the types of things that are akin to the arbitrary, absurd, oppressive thinking that went on during the Soviet Union.

Carolyn: Well you could make the observation that we have become a much more visual culture. We're not as oriented to words anymore. We don't tell jokes to each other but we send each other memes. And also the thing that I find really interesting is that this is, at least from appearances, not a top-down thing. The censorship has been bubbling up from the bottom. We censor ourselves now. We don't have the Czech police listening in on microphones anymore. Well we've got Alexa. Remember Lobaczewski's story about the professor who was an idiot? So throughout the 1960s on, our universities have been flooded with hundreds and thousands of these same idiot professors.

Elan: Yes.

Carolyn: And they have inculcated their crazy students, or the ones that are susceptible to it, and that has created this bottom-up self-censorship, this atmosphere of cancellation. So it's a little scarier when everybody around the corner is ready to leap on you.

Harrison: Yeah. There are a couple of things there. I think that you're right that we are more of a visual culture nowadays just because of the internet.

Carolyn: And smartphones.

Harrison: And emojis and text speak. We're not as literate as we used to be.

Carolyn: No.

Harrison: And part of the reason for the nature of the communist jokes, in addition to the pre-existing cultural thing, was that you could only tell these jokes in person. You could only communicate them orally. So it was this underground oral tradition, essentially, where you'd get together. I think he describes the process in the introduction. There was a process to it. So you'd get together with a group of friends and you'd start drinking and then eventually one would tell one joke and then they'd tell another joke and after that they'd just be going back and forth with all these jokes. It was almost kind of a ritual to get it all out of your system.

Whereas with where we are right now, we're not in the same cultural, societal position yet. It's not like you have to secretly go to your friend's house and go down to the basement and say, "Oh I heard this good joke!" You can send it in email. You can tell it at the water cooler or share it on your phone with someone. There's no oppressive external police force that you are afraid of. Right now, like you said, it's more of this bottom-up self-censorship. It's "Well maybe I shouldn't say that because that's not really appropriate or that might offend someone."

Elan: And you'll get a thousand people on Twitter excoriating you about something you've said.

Carolyn: Yeah, and trying to get you fired.

Elan: And trying to get you fired and compelling you to make some kind of public apology...

Harrison: Right.

Elan: ...and admission of your mistake and your insensitivity. It's almost no different from having the communist party...

Carolyn: The struggle sessions.

Elan: ...have somebody come before the party and admit his mistakes and then go to the gulag for a shorter period of time or be released from the gulag after only a few years. I mean, this is a milder version, I think.

Carolyn: But it's far more pervasive.

Elan: It has become far more pervasive. And that said, I think we do have a couple of memes here that are pretty good that say quite a bit about where people are ideologically. This one is of Rachel Maddow and it says, "Everything I don't like must be banned. Everything I do like is a human right and must be paid for by others." That's pretty good.

Harrison: It's a bit of a boomer meme. {laughter}

Elan: It is, but it's accurate as far as it goes I think.

Carolyn: Well it does fit the whole thing of - what do we call it? - packed to the hilt with information. Even somebody answering your tweet with "Okay boomer" carries a multitude, a huge amount of information. "I'm not a boomer. You're out of touch. My way is better. You are irrelevant." Two words! Two words is a huge amount of information compressed into that.

Harrison: Yeah.

Carolyn: So in a way it's still applicable, this idea of the joke. They've gotten a lot nastier though. These jokes, in their own way, are actually rather sweetly gentle. They're making a point but they're not vicious. These days the humour is vicious. You have to get a really tough hide for them.

Elan: Well here's another meme that we have that I think is pretty good too. "If you don't realize that the human population is being systematically dumbed down then you have been systematically dumbed down" which is true and speaks to what you were saying a few minutes ago Harrison, about the fact that we're so much less literate a society than we were 20 or 30 years ago. People don't write letters anymore. People probably read less. People are looking for the quick sound byte to get their information. We are a low information people even though we've never had as much information available to us as before.

So these are some ways that we can communicate some of the things that we're seeing around us. I'll just say I was a little inspired by Lewis' book Hammer and Tickle. I came up with a couple of so-so jokes that I wanted to read. I worked on them a little bit with a friend who gave me the this and the ha-ha. So we'll see. I'm going to read them and you guys'll laugh or not.

Harrison: Laugh or groan.

Elan: Or groan. One or the other, or maybe neither. This is the first one. Two American journalists who specialize in foreign policy meet and have lunch together at a trendy restaurant in Washington, DC. The first journalist writes for a conservative magazine and the second works for a neo conservative think tank that is funded by NATO. The conservative journalist can't contain himself and seeing the urgency in meeting with his colleague, begins by saying to the NATO-funded, deep state neo-conservative writer, "Look! NATO should stop acting so aggressively towards Russia! The missiles placed in Romania are aimed at Russia. The sanctions you guys continue to pile on! All the provocations around Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. If you guys keep escalating tensions then you'll do something even more stupid that will force Russia to defend itself militarily, which it will feel compelled to do and then who knows what will happen? It could lead to another world war. Many people might be killed. Cities in Russia, Europe, even here in the US could be destroyed. It could all lead to a horrible disaster. Why continue this madness?" The deep state journalist furrows his brow, clenches his teeth and looks deep in thought. Finally after the moment he has taken to collect himself, he answers, "You'd really rather have Russia be allowed to show its flag at the Olympics?"

Harrison: It's worth a chuckle.

Elan: I think you're being generous {laughter} but okay. I've got one more. I had a few more, but...

Harrison: Whittled it down?

Elan: Yeah, I whittled it down to two from four. Okay. This is it. "Shortly after the end of a big rally on climate change, Greta Thunberg is approached by a mild-mannered older gentleman who introduces himself as a credentialed climatologist with several science degrees and dozens of peer-reviewed papers on climate change under his belt. The scientist says to Greta, 'Young lady, I would like to offer you the opportunity to sit down with me and some of my colleagues where we can look at some of the key points in our research demonstrating that some global warming is a perfectly natural part of climate cycles, that the earth is not warming at a rate that some people are saying, that global climate is largely, in fact, dependent upon the cycles of sunspot activity and that we are now entering a major movement towards the cooling of our planet and that groups of people are using you towards a political and economic agenda that will actually end up hurting those you seek to help and protect. What do you say, dear lady? Can we meet to discuss all this?' Greta looks at the man and says, 'All of your science and facts and research doesn't make your understanding of climate change as hot as mine is!' {chuckles}

Okay. I tried. Well if nothing else, these jokes give one to understand just how difficult humour is {laughter} and how many jokes need to go into circulation before they can be...

Carolyn: It sifts out the good ones.

Elan: Sifts out the good ones from the bad ones. So Lewis said that he looked at over 40 books to write his book. There was quite an abundance of humour that was out there on communist Russia and the Soviet Union. But it also tells you how many people were focused and put energy into this outlet of humour.

Harrison: I'm pretty sure at one point he says that there were only actually about 1,100 unique jokes, that it wasn't this infinite supply of jokes. There was a limited number. In one sense that's a big number, 1,100, but in another sense it's not a very big number if you think about the millions of people that were telling these jokes.

Carolyn: So, unique and then the themes were adapted to local circumstance.

Harrison: Yeah, or it would just be the same joke and you'd just change the name and the location. So instead of Stalin it might be Ceaușescu or something like that, or instead of Russia it might be Hungary.

Carolyn: I read somewhere that there were only 64 storylines and that all of the literature of the world is drawn from these 64 basic themes. But people are people. There will be commonalities, especially if you're all labouring under the same constraints, you'll tend to find the same jokes.

Harrison: Yeah. I think it might be a bit of both. I think that for the most part it was just the same joke, down to a level of specificity that got adapted, just changing the names and countries and maybe there's also an element, like you were saying, of the 100th monkey, the same kind of conditions will lead to the same joke in different circumstances. It's hard to know exactly how these kinds of things happen. I'd lean more towards the direct transmission, maybe with an element of that 100th monkey but if you look at some of the studies on oral traditions and research like children's nursery rhymes and the games that they play in school and the sing-songy rhymes that they come up with, some of them have been around for hundreds and hundreds of years and potentially longer than that. There are some researchers that speculate that they've been around for thousands of years and they just travel all over the place. No one really knows exactly how. Somehow it just manages to go from school to school and city to city and all these kids are saying the same thing and playing the same games and making the same rhymes.

Carolyn: Maybe there's a certain amount of pattern recognition, that it sort of slots in.

Harrison: And it's like the good joke, the sieve that filters out the bad jokes and the good jokes, the rhymes are perfect in some way so kids naturally pick them up because they're so well constructed. They don't need to change. So these 1,100 jokes are the distillation of all the failed attempts at coming up with a good communist joke and then they just travel all over the place to the extent that this guy could find different books in different languages, published by different people, each claiming that their jokes are the original, unique, national treasure of their community and they're the exact same jokes.

That's the thing. No one knows one individual who wrote any of these jokes. No one knows the authors of any of them. They are just something that has sprung up. It's not like stand up comedians where you can oftentimes trace back a joke to one guy that came up with it.

I don't know what I wanted to say about that, but maybe in the context of modern humour, there is this oppressive climate where people feel they can't tell jokes and often can't because there will be some kind of repercussion, even if it's just character assassination and not hard labour for 25 years.

Carolyn: But look at the number of movies, like anything that Mel Brooks made, or movies from the 1960s, you just think that they could never show this again, or it would never get made again.

Harrison: Yeah, and some actors and writers are apologizing now...

Carolyn: For something they did 20 years ago?

Harrison: For the comedy movies, yeah, that they did 20 or 30 years ago.

Carolyn: It's insane.

Harrison: But we still have some comedians that are at least willing to stick their necks out and be the lightning rods for abuse and just say, "Screw it! I'm going to tell my jokes and people are actually going to laugh at them and I don't really care what you say about me." Just recently Dave Chappell and Bill Burr each had Netflix specials that were totally irreverent and politically incorrect, according to modern standards today, but they've been wildly popular, despite bad reviews from all of the newspaper editor class, people seem to like them. It's the rotten tomatoes phenomenon. You look at the critics and the critics give it a really low review, saying it's not even worth watching and the audience is giving it super high reviews and saying, "You've got to see this!"

So it's a lighter version of the underground phenomenon that you see in a totally closed society. Right now, to the extent that our society is closed, it's the walls that we've put up for ourselves, these imaginary walls that aren't dictated from some bureaucrat's office that are coming up with the rules and regulations. It's a societal consensus that's been going around and there is a figurative underground within this system of just regular people who find things funny and know what's funny and know what's not funny.

We should talk about that too. One other point. He points out that there were two types of humour in the communist countries. There was the underground humour and then there was the official humour. So you still had comedy and jokes in official culture, but that was the stuff that was approved by the censors and written by the propagandists. So you had your official satire, your official comedy, the stuff that was allowed and would serve a propaganda purpose. Then you had the underground one. Well we have a version of that too, where we have the mainstream, approved, politically correct comedy, which isn't funny at all.

Carolyn: At all.

Harrison: And then you've got the somewhat underground - I don't even know what word to call it...

Elan: Well I'd like to comment on something you just said, Harrison.

Carolyn: Fringe. You could call it fringe.

Harrison: Yeah.

Elan: Because you mentioned that there's this whole politically correct segment of comedy that's approved. There was a YouTube personality, she's an Indian woman. I forget her name, I'm just going to say Indira Singh, but apparently she had this very successful YouTube program and she made the transition to prime time late night. I don't know what channel or station she's on, but there were clips shown of her program and the one running theme throughout her entire show is that she's not a white man. She sings about it. She mentions it during most programs and she's conventionally politically correct.

As one observer put it, there is absolutely nothing funny about her and all the clips that he played of her show were horribly not funny! Or utterly banal! And she parlayed this YouTube personality she created into this very idiotic, juvenile, politically correct, humourless, toothless, lack of insight, lack of intelligence, program!

Carolyn: Wow!

Elan: And it was interesting that this commentator on YouTube, who I'd never heard of, his particular program had over 3 million views or some crazy high number, which said to me that there are a lot of people who have the same observation and who are interested in the fact that she has become this personality who has managed to parlay her idiotic routine into this mass consumed program and she's talentless! So there is that flip side.

Carolyn: Well people are getting braver. When I saw most of Dave Chappell's thing, the first thing I thought was this is a man who's made his money and just doesn't care anymore and if this is a career-ending show, he's totally fine with it, which I thought was a wonderful stance to take. It's a gamble that paid off. But there was another comic. He's an Indian guy and he is funny, he can be funny, but he went off on the same kind of riff, basically if you're white, you're useless and pointless, blah, blah, blah, trying to be funny about it. People got up and walked out, left the show.

Elan: Good.

Carolyn: There are people who are just finally saying, "You're not funny. I don't care if I paid for a ticket. I'm leaving." So maybe that tipping point is coming, where people just go, "Yeah, Dave Chappell, you rock! Mr. Burr, carry on!"

Elan: It's almost as though even if it's offensive, if there's an element of truth about it that people can recognize, that people find familiar, that people have on the tip of their tongues or the edge of their awareness that is brought into the light of an explanation through the form of a joke, they celebrate it! That was George Carlin's genius. He could go up there and insult certain segments of the population or certain ideas because he had the conviction, based on truth, based on real powers of observation that he had, that he was correct and he knew how to deliver it.

Carolyn: Well the best ones take no prisoners. The best ones, you're all up for it. If you only have one hobby horse to ride in on, you're not really a comedian, not somebody who's really going to use your gift for the benefit of all and for the mocking of all.

Harrison: Well I think to wrap up, I'm going to tell a few more jokes and read the epigraphs - is that the word? - that Lewis includes at the beginning of his book. Maybe I'll start with the epigraphs and with the jokes. The first is from Anthony Ashley Cooper, the third Earl of Shaftsbury. "The higher the slavery, the more exquisite the buffoonery."

Then Ernst Rohl in an interview with the author, "It's the law of Faust. The worse the times, the better the jokes." And then finally, from the master himself, Karl Marx, "The final phase of a historic political system is comedy." Proved correct I think.

Carolyn: Oh boy!

Harrison: So Marx had it right.

Elan: About something.

Harrison: Yeah. Now just a few jokes. We didn't tell the classic one which was everywhere in the communist countries. "So long as the bosses pretend to pay us we will pretend to work." And now a couple more anecdoti. "Midnight, Petrograd. A red guard's night watch spots a shadow trying to sneak by. 'Stop! Who goes there? Documents!' The frightened person chaotically rummages through his pockets and drops a paper. The guard's chief picks it up and reads slowly, with difficulty. 'Urine analysis. Hmm. A foreigner sounds like. A spy looks like. Let's shoot him on the spot.' Then he reads further. 'Proteins, none. Sugars, none. Fats, none. 'You are free to go proletarian comrade. Long live the world revolution!'

Another. Question, is it true that there is freedom of speech in the Soviet Union just like in the USA? Answer, in principle yes. In the USA you can stand in front of the White House in Washington, DC and yell 'Down with Reagan' and you will not be punished. Equally, you can stand in Red Square in Moscow and yell, 'Down with Reagan and you will not be punished.' {laughter}

Maybe one final one. This is another good Stalin one. "A secretary is standing outside the Kremlin as Marshal Zhukov leaves a meeting with Stalin and she hears him muttering under his breath, 'Murderous moustache!' She runs in to see Stalin and breathlessly reports, 'I just heard Zhukov say murderous moustache!' Stalin dismisses the secretary and sends for Zhukov who comes back in. 'Why who did you have in mind with murderous moustache?' ask Stalin. 'Why, Josef Vissarionovich, Hitler of course!' Stalin thanks him, dismisses him and calls his secretary back. 'And who did you think he was talking about?' {laughter}

So with that said, if you want some more communist jokes then check out Hammer and Tickle by Ben Lewis.

Carolyn: And an excellent analysis of communism from its beginning to its end.

Harrison: Yes, indeed.

Carolyn: In jokes.

Harrison: Then check it out and if you happen to have any good communist jokes, put them in the comments on YouTube because we'd love to hear them. So thanks everyone and we'll see you next year. This will be our last show of the year. We'll see you in 2020.

Elan: And we hope that your Christmas and holidays are healthy and happy and filled with lots of good things and some good humour, that isn't politically correct and we'll see you again soon. Thanks for listening everyone.

Carolyn: And Merry Christmas, if we're going to be politically incorrect.

Elan: I started with Merry Christmas but I added the happy holidays.

Carolyn: Right.

Harrison: And give yourself a nice present next year by hitting the subscribe button and finding out when our new show is coming out.

Carolyn: And tell a friend.

Harrison: Take care everyone.

Reader Comments

You are in the room with Barack, Hillary and Joe and you only have two bullets...what do you do?

Shoot yourself in the head. Twice

RC

R.C.

And don't forget the less than happy ending for Boxe r, the draft horse in Animal Farm.

R.C.

Americans like to gloat about the overt criticism of the USSR by Orwell, but seem to miss the (rather obvious) point of the book entirely which was the failure of the Animal Farm (symbolizing an island, national-level revolution) was the failure to overthrow the the capitalist system, which was the problem in the first place. It was an anarchists warning for socialists, not about socialists.

"The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which."

In my book, liberals (original definition) when forced to it - while acknowledging their potential for error*** - would err on the side of 'having a government';

Likewise, in my book, conservatives (original definition) when forced to it - while acknowledging their potential for error*** - would err on the side of 'NOT having a government'. (I err towards the latter, but like to believe I retain an open mind. )

I have for years, decades...likely over

50% 1/10th**** of my life . . . been well aware of that divide and, after the Fall of the Wall, and seeing black and white kids playing together, looked forward to that honest (and never violent) debate. Same would and should have occurred with the at around the time of the (VERY) shortly discussed "Post-Cold War Peace Dividend."***** It never did. (Duh.)Using but two examples, I've concluded that while WRH would, if push came to shove on that question, err on the side of 'no government'; that SOTT would err on the side of 'a government.' I find both sites worthwhile.

But of course the Divide and conquer protocols/SOP of the scum who see themselves as our 'masters', hope folks DO get into a disconnective disagreement on X, Y, Z, AND, most particularly, THIS point.

The problem, of course, with that is that in any and all such politically esoteric debates, we can rest assured that, nowadays, the end result (as presented to the proles) will be received by them unquestioningly and thus will only yield more fodder for the PTB's MSM to aim at (or from), calling conservatives 'fascists' or 'anarchists', while calling those who conclude government as a necessity, 'socialists'/Socio-communists/'Marxists'/Commies, etc.

Thus, the most important approach for all of us is that we, with one voice, tell the professional liars of the PTB, MSM, et al., is to kiss our respective asses, be they white, black, or. . . green!!! Argh.

R.C.

*Which such discussions/debates most often occured in Ancient Greece; the Russian Revolution era; and, e.g., most recently, (likewise, another 'expired'/'extinct' era of freedom where one could publicly speak their beliefs) in, say, a Doctoral Class in Political Science.

**On purpose;

*** If any person claims otherwise, they are not worth the time writing to or speaking with;

**** I figure since it's Christmas, I'd like to keep my chances for a longer life higher. (Silly, non sequitur, but gotta go - sorry for not rewriting better.)

***** Younger SOTTfolks: do YOU remember that phrase? Was it taught to you? Either way - ask yourselves, "Why not?" RC

Spread that gospel!

R.C.

You might have been misled by one of my previous comments. That gretasque persona, however, was created specifically for the occasion. Still, your comment came out a bit teasy.

Still further, considering my generation, as well as population at large, you might have actually evaluated me correctly.

It should not then come as a surprise that I am a little wary of gospels. And of preaching in particular.

That was 'friendly Southern talk' and nothing more. Saying somethin is 'gospel' around here really carries NO religious connotations/implications whatsoever. My father HATED chuch but saying that x was 'gospel' = true, was one of his - and is one of my - common expressions. Note: as a result, my family NEVER attended ANY church, etc. Instead, I surfed at the Church of the Atlantic.

I never read the bible until I found a discarded WWII infantryman's pocket bible in the trash on the Winter Solstic 2001. (I'd stopped for the dresser.) It was loaded with first editions, including 'To Kill a Mockingbird,' 'The Old Man & the Sea', et al. (Over 5K worth of books.)

I've never been known to be 'teasy' and there's never a need to read in between my lines.

But I won't hesitate to tell someone who's being a jerk to 'kiss my *ss'. Indeed, I recently did so and even followed up with a poem to such a scumbag. "In Memory of Pee Donnelly, in the comments at:

SOTT Focus:'Undeniable Evidence': Explosive Classified Docs Reveal Afghan War Mass Deception

In what's already being hailed as a defining and explosive "Pentagon papers" moment, a cache of previously classified documents obtained by The Washington Post show top Pentagon leaders...So no worries, my friend. I hope you had a great Chriistmas and we all have a great new year - we damn sure deserve it.

R.C.

RC

Merry Christmas everyone!

R.C.

"Merry Christmas, my friend."

R.C.

And a scary thing it must be/is for any hopeful standup comic (the TOUGHEST) performing job (save being a hooker, I guess ) that's out there.

The end result? See SCOTUS' opinions of Brennan and Douglas re 'chilling effect.'

RC

I hope to finish this, before she finishes singing.

Years ago, I wrote to you about Poe's views on beauty and truth, poetry, music. You claimed/'feigned'? ignorance.

But YOUR video links are just about the only ones I've bothered to watch.

Merry Christmas!!!! (And the song's just ending.... Silent Night, Holy Night to all SOTTfolk, and kind souls.

RC

I've always been a bit of a Kathleen Ferrier freak....[Link]

My father was a great poet- His favorite poem was Annabelle Lee.

Check this out.[Link]

I believe that he was, relatively, FWIW, a Scotsman by upbringing, if not by genes.

R.C.

*I've even fell in love once with a lady where a huge factor was that she was smarter than me. (Yeah, she was one of the 'three')

MERRY CHRISTMAS!

RC

Nonetheless, I forgot having given to you my friend, a poe commentary about Furniture that, for reasons unknown to me at present, I believe that you may well find entertaining.

Again, here it is:

The Poetic Principle, AND, The Philosophy of Furniture both at [Link]

R.C.

It is NOT original to me.

RC