Do your genes, rather than upbringing, determine whether you will become a criminal? Adrian Raine believed so – and breaking that taboo put him on collision course with the world of science

In 1987, Adrian Raine, who describes himself as a neurocriminologist, moved from Britain to the US. His emigration was prompted by two things. The first was a sense of banging his head against a wall. Raine, who grew up in Darlington and is now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, was a researcher of the biological basis for criminal behaviour, which, with its echoes of Nazi eugenics, was perhaps the most taboo of all academic disciplines.

In Britain, the causes of crime were allowed to be exclusively social and environmental, the result of disturbed or impoverished nurture, rather than fated and genetic nature. To suggest otherwise, as Raine felt compelled to, having studied under Richard Dawkins and been persuaded of the "all-embracing influence of evolution on behaviour", was to doom yourself to an absence of funding. In America, there seemed more open-mindedness on the question and, as a result, more money to explore it. There was also another good reason why Raine headed initially to California: there were more murderers to study than there were at home.

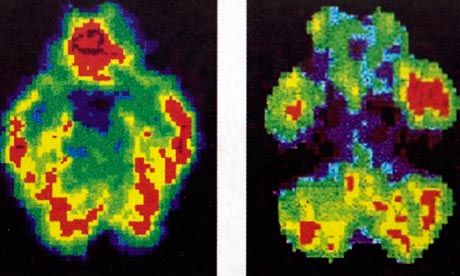

When Raine started doing brain scans of murderers in American prisons, he was among the first researchers to apply the evolving science of brain imaging to violent criminality. His most comprehensive study, in 1994, was still, necessarily, a small sample. He conducted PET [positron emission tomography] scans of 41 convicted killers and paired them with a "normal" control group of 41 people of similar age and profile. However limited the control, the colour images, which showed metabolic activity in different parts of the brain, appeared striking in comparison. In particular, the murderers' brains showed what appeared to be a significant reduction in the development of the prefrontal cortex, "the executive function" of the brain, compared with the control group.

Comment: The root confusion here is the failure to distinguish between violent criminals and psychopaths. Violent criminals make up a tiny fraction of psychopaths. Most psychopaths never physically harm anyone and thus remain 'sub-criminal', i.e. below the radar.

How full-time researchers still have not grokked this staggers the mind...