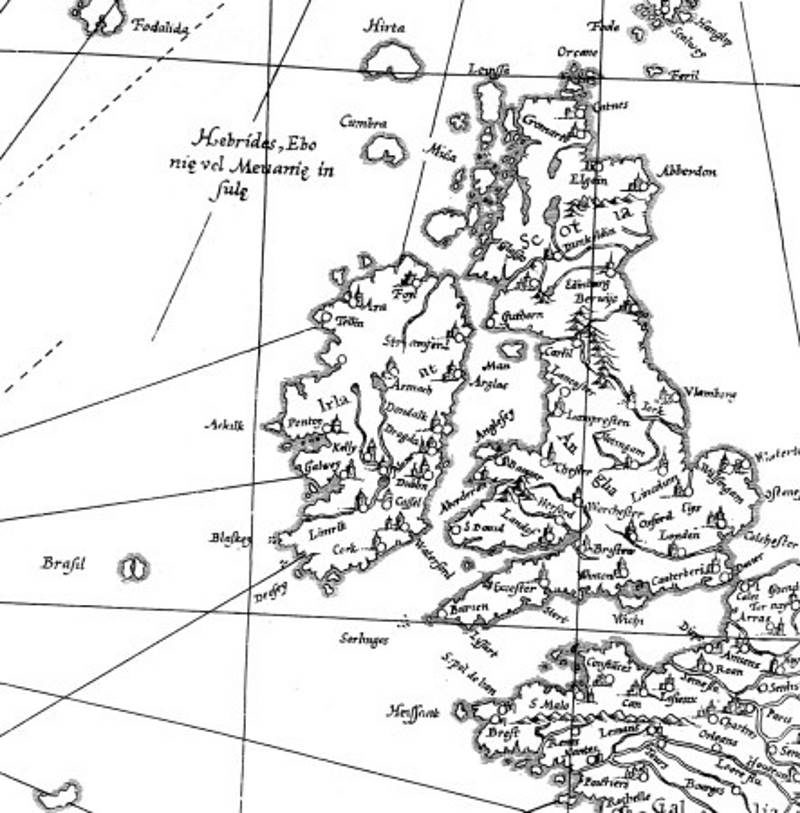

Local Irish tradition knows of an Árainn Bheag or 'Little Aran', which sometimes can be encountered west of the 'big' Aran of real-world topography. This Little Aran is the same island as the isle of Hy Brazil that appears on maps as prominent in the history of cartography as the world map of Gerhard Mercator and that was the destination (though never reached) of a number of voyages of exploration that set sail from Bristol in the 1480s, just a few years before, from the same harbour, John Cabot put to sea to become the first European after the Vikings to set foot on the North American mainland.

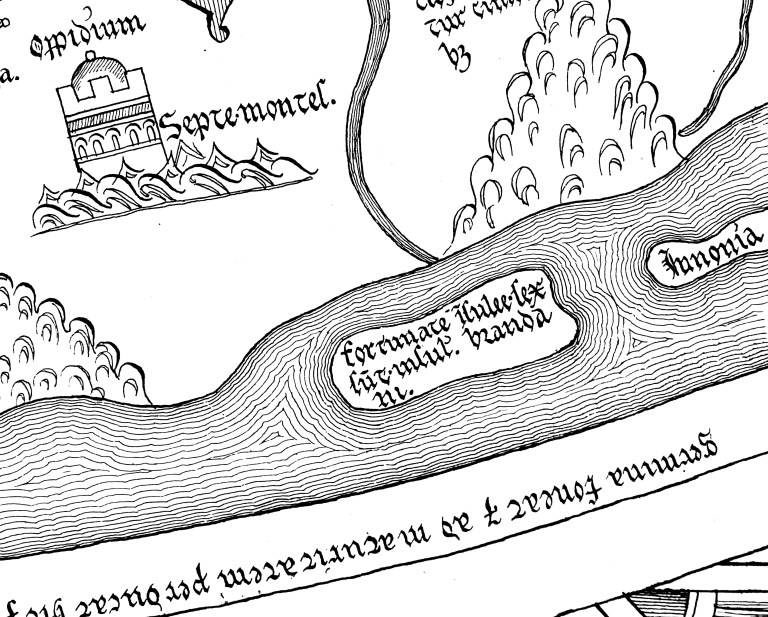

The world map of Hereford, created around AD 1300, is only one of many examples of prominent historical maps that allocated a place in the real world to these islands of Christian myth. In the Atlantic to the west of North Africa, the Hereford map plots a chain of islands with the legend: fortunate insulee sex sunt insule sancti Brandani, 'the six Islands of the Blessed are the Islands of Saint Brendan'. Setting out from the ports of Europe, generations of explorers later on tried to locate this saintly world of islands, the last documented expedition in search of 'Saint Brendan's Island' setting sail as late as the year 1727.

Even the first account of the Norse discovery of North America in Adam of Bremen's History of the Bishops of Hamburg, probably written in the 1070s and 1080s, appears to recount a Norse adaptation of non-Norse topoi. Adam's account of Canada (Winland, 'Wine-Land') is so clearly modelled on classical Graeco-Roman accounts of the Islands of the Blessed that Adam himself pauses and emphasises the reliability of his sources, trying to cover the obvious use of classical motifs, which he himself notices, by stressing the literal truth of his account.

There seems to be a convoluted but ultimately direct line that leads from Homer's Odyssey, where, in the guise of the Elysian Plain, the Islands of the Blessed are first attested in European literature, to the Norse account of the discovery of North America. From the Greek 'Islands of the Blessed' (μακάρων νῆσοι, makaron nesoi) the way led to the Roman 'Blessed Isles' (Insulae Fortunatae), which, through the learning of Late Antiquity as it is represented by Isidore of Seville, influenced early medieval Irish conceptions of paradise islands, which in turn were adopted and adapted by the Norse. The resulting complex web of entanglements made it possible that the Norse sailors who told their tales to Adam of Bremen could use the same imagery of the Islands of the Blessed, which the world map of Hereford uses to locate the Gaelic imaginary islands of the 'Voyage of Saint Brendan'.

At the same time, one wonders whether the Norse reception of Gaelic motifs, and of classical motifs mediated by Irish storytelling and learning, might not perhaps have done more than just colour stories. If the Norse of the Viking Age in Ireland were told of miraculous, paradisiacal islands in the west, was this received simply as a story? Or was it thought of as a promise and an incitement to push the boundaries of Norse exploration even further? Was Winland described in the imagery of the Islands of the Blessed merely because this imagery constituted a convenient topos to model a description on, or had the discoverers of Winland been chasing a classical geographical dream and thought they had found it?

In short, was the Norse westward expansion partly inspired by a mythology that had its origins in the Mediterranean of classical antiquity and which had been transmitted to the Norse via Ireland?

Looking west from the cliffs of Aran, one certainly sees how visions of an Árainn Bheag or 'Little Aran' might arise from the shapelessness of the distant, disappearing horizon and how they could crystallise into a 'Paradise of God in the vastness of the sea' or a Hy Brazil to lure explorers farther and farther out into this very 'vastness of the sea', where rewards as precious as the 'Paradise of God' were awaiting. Whatever may be the role that Irish and classical geographical mythology played for the Norse westward expansion and ultimately for the Norse discovery of North America, this allure, and how its stories were passed on from one European seafaring culture to the next, certainly forms a central longue durée of medieval European maritime history up to the Age of Discoveries.

Matthias Egeler holds a Heisenberg fellowship at the Institut für Nordische Philologie of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich and is Fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. He is the author of Islands in the West. Classical Myth and the Medieval Norse and Irish Geographical Imagination, published by Brepols. .

Comment: The author is closer than he thinks to an answer, but just not in the way he imagines.

Where Troy Once Stood: The Mystery of Homer's Iliad & Odyssey Revealed