© Eben Alexander III, M.D.Proof of Heaven by Eben Alexander, M.D. To be published by Simon & Schuster, Inc..

As a neurosurgeon, I did not believe in the phenomenon of near-death experiences. I grew up in a scientific world, the son of a neurosurgeon. I followed my father's path and became an academic neurosurgeon, teaching at Harvard Medical School and other universities. I understand what happens to the brain when people are near death, and I had always believed there were good scientific explanations for the heavenly out-of-body journeys described by those who narrowly escaped death.

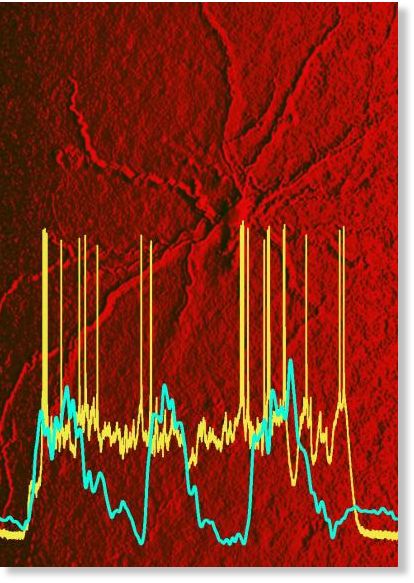

The brain is an astonishingly sophisticated but extremely delicate mechanism. Reduce the amount of oxygen it receives by the smallest amount and it will react. It was no big surprise that people who had undergone severe trauma would return from their experiences with strange stories. But that didn't mean they had journeyed anywhere real.

Although I considered myself a faithful Christian, I was so more in name than in actual belief. I didn't begrudge those who wanted to believe that Jesus was more than simply a good man who had suffered at the hands of the world. I sympathized deeply with those who wanted to believe that there was a God somewhere out there who loved us unconditionally. In fact, I envied such people the security that those beliefs no doubt provided. But as a scientist, I simply knew better than to believe them myself.

In the fall of 2008, however, after seven days in a coma during which the human part of my brain, the neocortex, was inactivated, I experienced something so profound that it gave me a scientific reason to believe in consciousness after death.

I know how pronouncements like mine sound to skeptics, so I will tell my story with the logic and language of the scientist I am.

Very early one morning four years ago, I awoke with an extremely intense headache. Within hours, my entire cortex - the part of the brain that controls thought and emotion and that in essence makes us human - had shut down. Doctors at Lynchburg General Hospital in Virginia, a hospital where I myself worked as a neurosurgeon, determined that I had somehow contracted a very rare bacterial meningitis that mostly attacks newborns. E. coli bacteria had penetrated my cerebrospinal fluid and were eating my brain.

When I entered the emergency room that morning, my chances of survival in anything beyond a vegetative state were already low. They soon sank to near nonexistent. For seven days I lay in a deep coma, my body unresponsive, my higher-order brain functions totally offline.

Then, on the morning of my seventh day in the hospital, as my doctors weighed whether to discontinue treatment, my eyes popped open.