© Photos.com

How many times have you driven a route that you were familiar with, made it safely to your destination, and then realized that you can't recall any of the specifics of your journey? Maybe you were focusing on the music on the radio or the stress of the day. Perhaps in our increasingly digital existence, you were paying attention to incoming texts or listening to the turn-by-turn directions of your GPS unit.

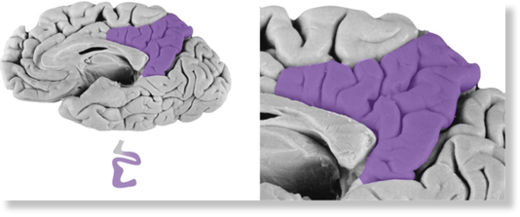

This psychological condition, known as 'inattentional blindness', occurs when we increase our memory load with information that deflects our attention from the task at hand. When we are focused on tasks or specific information, we can sometimes be effectively blind to things that are in plain sight.

Numerous real-world examples have been documented over the years. Workers in the medical or law enforcement fields - professionals regarded as educated, intelligent and even methodical - have botched their jobs in a manner that appeared careless or negligent and often led to dangerous or even fatal outcomes on account of inattentional blindness or the related phenomenon known as '

inattentional deafness'.

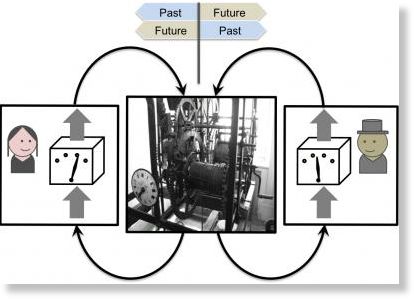

According to a new study commissioned by the

Wellcome Trust, when we try to keep an image we've just seen in our memory, we can blind ourselves to things we are actually looking at.

A fun example, the now famous

'invisible gorilla' experiment, involves observers who are watching a video of basketball players passing around a basketball. They are asked to focus on and count the number of times the players pass the ball to one another. While focused on this task the observers fail to see a man in a gorilla suit who walks directly across the center of the screen.

While the 'invisible gorilla' experiment is an interesting way to explain this phenomenon, not all examples are so light-hearted. In 1995, while responding to a downed officer, several police cars began to pursue four suspects who had fled in a car. According to Dick Lehr, a reporter for the Boston Globe, "Cops were flying in from all over. There were more than 20 cruisers involved at different points in the chase." The vehicle chase finally came to an end in a cul-de-sac when all four suspects fled on foot in different directions.