© DreamstimeThe ability to recognize oneself in the mirror is a basic aspect of self-awareness.

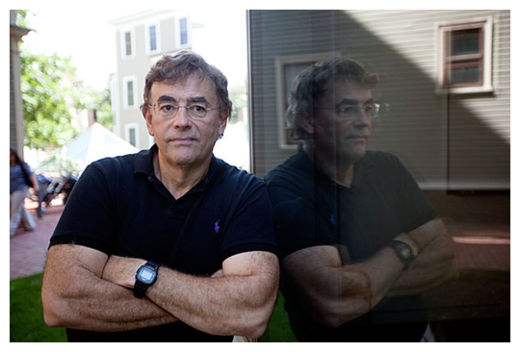

According to some theories on how self-awareness arises in the brain, Patient R, a man who suffered a severe brain injury about 30 years ago, should not possess this aspect of consciousness.

In 1980, a bout of encephalitis caused by the

common herpes simplex virus damaged his brain, leaving Patient R, now 57, with amnesia and unable to live on his own.

Even so, Patient R functions quite normally, said Justin Feinstein, a clinical neuropsychologist at the University of Iowa who has worked with him. "To a layperson, to meet him for the first time, you would have no idea anything is wrong with him," Feinstein said.

Feinstein and colleagues set out to test Patient R's level of self-awareness using a battery of tools that included a mirror, photos, tickling, a lemon, an onion, a personality assessment and an interview that asked profound questions like "What do you think happens after you die?"

Their conclusion - that Patient R's self-awareness is largely intact in spite of his brain injury - indicates certain regions of the brain thought crucial for self-awareness are not.

Brain anatomySelf-awareness is a complex concept, and neuroscientists are debating from where it arises in the brain. Some have argued that certain regions in the brain play critical roles in generating self-awareness.

The regions neuroscientists have advocated include the insular cortex, thought to play a fundamental role in all aspects of self-awareness; the

anterior cingulate cortex, implicated in body and emotional awareness, as well as the ability to recognize one's own face and process one's conscious experience; and the medial prefrontal cortex, linked with processing information about oneself.

Patient R's illness destroyed nearly all of these regions of his brain. Using brain-imaging techniques, Feinstein and colleagues determined that the small patches of tissue remaining appeared defective and disconnected from the rest of the brain.

Comment: There are others methods that naturally stimulate vagus nerve for relaxation.Éiriú Eolas stress-control, healing, rejuvenation Program is a proven program that stimulates the vagus nerve to control stress, pain relief and rejuvenate body/mind