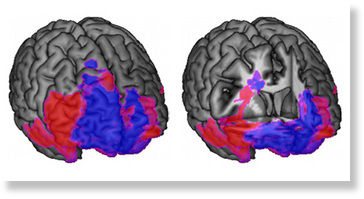

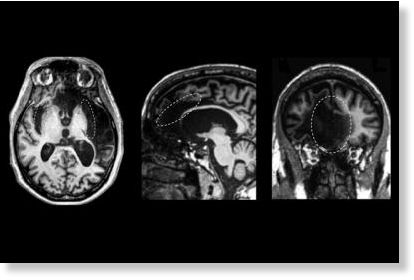

© Department of Neurology, University of IowaResearchers at the University of Iowa studied the brain of a patient with rare, severe damage to three regions long considered integral to self-awareness in humans (from left to right: the insular cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex). Based on the scans, the UI team believes self-awareness is a product of a diffuse patchwork of pathways in the brain rather than confined to specific areas.

Ancient Greek philosophers considered the ability to "know thyself" as the pinnacle of humanity. Now, thousands of years later, neuroscientists are trying to decipher precisely how the human brain constructs our sense of self.

Self-awareness is defined as being aware of oneself, including one's traits, feelings, and behaviors. Neuroscientists have believed that three brain regions are critical for self-awareness: the insular cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex. However, a research team led by the University of Iowa has challenged this theory by showing that self-awareness is more a product of a diffuse patchwork of pathways in the brain - including other regions - rather than confined to specific areas.

The conclusions came from a rare opportunity to study a person with extensive brain damage to the three regions believed critical for self-awareness. The person, a 57-year-old, college-educated man known as "Patient R," passed all standard tests of self-awareness. He also displayed repeated self-recognition, both when looking in the mirror and when identifying himself in unaltered photographs taken during all periods of his life.

"What this research clearly shows is that self-awareness corresponds to a brain process that cannot be localized to a single region of the brain," said David Rudrauf, co-corresponding author of the paper, published online Aug. 22 in the journal

PLOS ONE. "In all likelihood, self-awareness emerges from much more distributed interactions among networks of brain regions." The authors believe the brainstem, thalamus, and posteromedial cortices play roles in self-awareness, as has been theorized.

The researchers observed that Patient R's behaviors and communication often reflected depth and self-insight. First author Carissa Philippi, who earned her doctorate in neuroscience at the UI in 2011, conducted a detailed self-awareness interview with Patient R and said he had a deep capacity for introspection, one of humans' most evolved features of self-awareness.