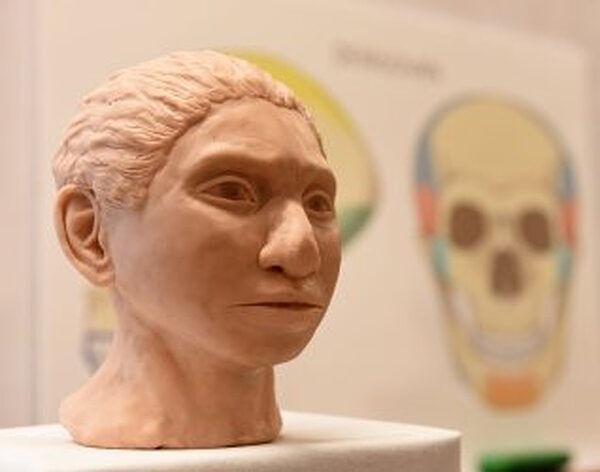

What Denisovans looked like or how they lived has remained a mystery, however. Only a jaw fragment, a few bits of bone and one or two teeth provide any evidence of their physical characteristics.

Their DNA, which was first found in samples from the Denisova cave in Siberia in 2010, provides most of our information about their existence.

But recently scientists have pinpointed a strong candidate for the species to which the Denisovans might have belonged. This is Homo longi - or "Dragon man" - from Harbin in north-east China. This key fossil is made up of an almost complete skull with a braincase as big as a modern human's and a flat face with delicate cheekbones. Dating suggests it is at least 150,000 years old.

"We now believe that the Denisovans were members of the Homo longi species," said Prof Xijun Ni of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, last week. "The latter is characterised by a broad nose, thick brow ridges over its eyes and large tooth sockets."

The possible Denisovan-Homo longi link is one of several recent developments by researchers working on these humans with whom Homo sapiens shared the planet for hundreds of thousands of years. It is even thought they could have played a key role in our own evolution.

Scientists in Tibet have discovered a Denisovan gene in local people, the result of interbreeding between the two species in the distant past. Crucially, this gene has been shown to help modern men and women survive at high altitudes.

In addition, evidence to support the Denisovan-Homo longi link has also been traced to the Tibetan plateau, where scientists began studying a jawbone initially found in a remote cave 3,000 metres (10,000ft) above sea level by a Buddhist monk, who kept it as a relic.

The bone was found not to come from a modern human. But only when researchers began to study the cave where the jawbone had been originally discovered did they find its sediments were rich in Denisovan DNA. In addition, it was found the fossil itself contained proteins that indicated Denisovan origins.

"It was the first time a Denisovan fossil find had been made outside Siberia and that was very important," said Janet Kelso of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. "Equally intriguing was the fact that the jawbone has teeth that are similar to the teeth found in Homo longi. So I think the evidence suggests a link between the cranium and Denisovans"

This view was backed by Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London. "The evidence supports the idea that Denisovans were members of Homo longi but we are still short of absolute proof. Nevertheless, that will come with time, I believe."

A big problem for researchers has been the fact that no DNA has yet been found in Chinese fossils such as Homo longi, added Stringer. "Their genes have not survived the passing of time. However, using the techniques of proteomics may provide key new data. These focus on a fossil's proteins, which survive for far longer than its DNA and could tell us much more about the species."

Recent research also suggests these people might have played a key role in the evolution of our own species.

The impact of the Denisovan gene found in Tibetans today provides one example. But Denisovan DNA has also been found in other modern populations, including people in New Guinea, northern Australia and the Philippines, and appears to have helped them fight infections from diseases such as malaria.

Denisovans settled in areas that covered a very varied geography, said Stringer. "Some were hot and low-lying, others were cold and mountainous. They represented very diverse habitats, from the Tibetan plateau to islands like Sulawesi [in Indonesia]."

By contrast, the Neanderthals, the third large grouping of humans that evolved over the past few hundreds of thousands of years, confined themselves to the cooler climates of a region that stretched east from Europe to southern Siberia.

Comment: Bearing in mind the assumptions regarding a region's climate are up for debate: Of Flash Frozen Mammoths and Cosmic Catastrophes

They did not expand from this relatively uniform environment. So is the rich variety of homelands adopted by the Denisovans a sign that they were capable of much more diverse and adaptive behaviour than Neanderthals, scientists are now asking?

Comment: Further clues may be found in the artefacts left behind; because Neanderthals aren't known for their ingenuity.

Homo sapiens also appears to have interbred with Denisovans on more than one occasion. "Indeed, there is good evidence that some modern humans interbred with genetically distinct Denisovans on multiple occasions," said Kelso. "This suggests that the two groups coexisted for an extended time, with some studies suggesting a last contact as recently as 25,000 years ago."

Crucially, by this time, Neanderthals were already extinct.

Research being carried out by Ni and Stringer also suggests that of the three main bands of humans who evolved at this time, Homo sapiens and the Homo longi group were the last to diverge on different evolutionary pathways, possibly a million years ago, with the Neanderthals branching off even earlier.

However, DNA analyses have suggested more recent divergence dates, with Homo sapiens splitting off first, so this is a crucial question for future research, said Stringer.

"How often our paths crossed after that parting of the ways is also now a topic of intense scientific interest," he added. "We have got so much to learn."

Comment: See also: