The Australian government's handling of the Afghanistan war crimes scandal has been an utter shambles and, as a result, those responsible are likely to escape punishment entirely.

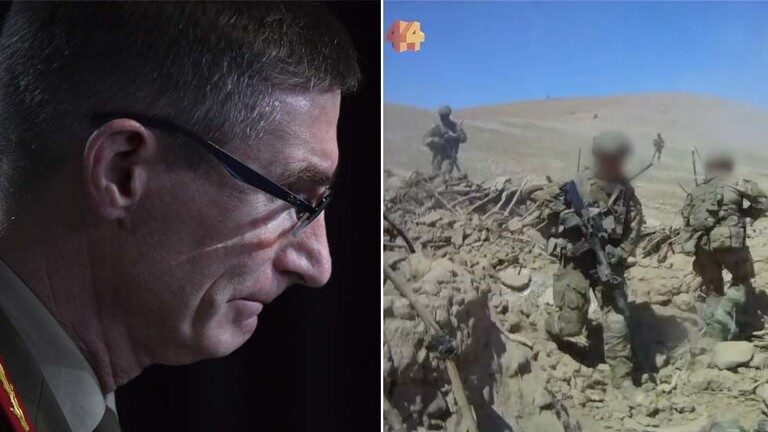

The Brereton report, handed down last week in redacted form, found that some unnamed 25 soldiers in the elite Australian special forces had committed 39 murders while on duty in Afghanistan. Brereton correctly described this as "a disgraceful and profound betrayal."

The report (very conveniently) then went on to completely exonerate upper-echelon army officers - on the grounds that they did not have a "sufficient degree of command and control to attract the principles of command responsibility."

This is notwithstanding that, as prominent Australian commentator Alan Jones pointed out this week, this finding is contrary to the "Yamashita Standard" which holds that "a Commander can be held accountable for crimes committed by his troops, even if he did not order them, did not know about them or did not have the means to stop them."

The government established the Brereton inquiry more than four years ago, amidst rumours and media speculation about atrocities having been committed by Australian troops in Afghanistan.

Why has the inquiry taken such an inexplicably long time to complete?

The main Nuremberg trials were completed in less than a year and the inquiry into American atrocities at Abu Ghraib was finalised just as quickly; and in both those cases punishments were immediately imposed on the guilty.

This unconscionable delay has been made worse by Prime Minister Scott Morrison's extraordinary announcement this week that yet another inquiry is to be established, and that, only when that has been completed will any criminal prosecutions of the murderers commence.

Some of the atrocities described in the Brereton report took place more than 10 years ago.

What realistic possibility is there that the perpetrators of these crimes will be found guilty by Australian juries in civilian criminal trials that will take place in perhaps five or 10 years' time? Bear in mind that none of the evidence gathered by Brereton will be admissible in those trials.

Justice delayed is justice denied, and you could not design a system more favourable to the guilty if you tried.

Having exonerated the entire top army brass, and ensured that the likelihood of conviction for lower-ranking perpetrators is minimal, what has the Australian government done in the past week to convince world opinion that it takes the atrocities committed in Afghanistan seriously?

It has engaged in an orgy of outpourings of sentimental remorse, and has taken a number of actions that will do absolutely nothing to bring to account those responsible for the atrocities committed in Afghanistan.

First, Defence Minister Linda Reynolds announced that she was "physically sick" after reading the Brereton report. Well she might be. How this was relevant to the serious issues at hand she did not go on to explain.

Prime Minister Morrison apologised to the President of Afghanistan and the Afghani people, and promised compensation to the families of victims - no doubt hoping to ward off legal proceedings of the kind brought by the families of those tortured at Abu Ghraib against the American government.

Then Chief of the Australian Defence Force, General Angus Campbell, announced that the Meritorious Unit Citation, which had been bestowed collectively upon all special forces soldiers who served in Afghanistan, would be revoked. This stripped the award from some 3,000 soldiers, some of whom had died in action - even though the Brereton report had only made adverse findings against 25 unnamed soldiers.

This action, in effect, branded all 3,000 soldiers who served in Afghanistan as murderers. The Taliban - not noted for their adherence to the Geneva Convention - were quick to pick up on this, describing the Australian armed forces as "savage degenerate invaders."

General Campbell had been the commander of Australia's troops in Afghanistan in 2011-2012 and had received a Distinguished Service Cross for his efforts. Campbell did not, of course, consider revoking his own award.

The Chief of the Army, Lieutenant General Rick Burr, a former special forces commander, announced that he was "sickened" by Brereton's findings.

Predictably, attacks were launched by the "cancel culture" brigade on the Australian War Memorial in Canberra - the closest thing that Australia has to a national shrine - because, naturally enough, it has a section devoted to soldiers who had served in the Afghanistan war.

More rabid activists have made calls for the immediate resignation of the War Memorial's Chairman, and for the Memorial and the "warrior culture" it allegedly promotes to be dismantled.

These actions have had the effect of completely destroying morale within the Australian armed forces, at a time when military tensions are increasing in South East Asia and America is withdrawing from the region.

More tragically, nine soldiers who had served in Afghanistan (a particularly vulnerable group of veterans even before recent events) have committed suicide in the past three weeks. The soldiers - one woman and eight men - were aged from their early 20s to their 50s.

There's no suggestion that any of them were linked to war crimes but veterans said the coverage - and the blame being pinned on squaddies - was undoubtedly the catalyst for the unprecedented spate of suicides.

Neil Wallace, a veterans' mental health advocate, told The Adelaide Advertiser: "I think some of the media [reports of alleged war crimes] has been painting everyone with the same brush, and people seem to have forgotten about innocence until proven guilty - and that adds additional stress."

Leaving aside the issue of punishment of the guilty, the misguided and unnecessary actions by the government and the defence-force elites have prevented a meaningful debate, about why the atrocities in Afghanistan happened, from taking place.

Relevant questions, which should have been considered but have not been, include the following:

1. Why were Australian troops in Afghanistan in the first place?

2. Was Australia's military strategy in Afghanistan fundamentally flawed?

3. Why were Australian special forces soldiers permitted to serve multiple tours of duty in Afghanistan?

4. Why wasn't an effective and timely inquiry process established by the government years ago when the atrocities first came to light?

5. Is Brereton's finding, that upper-echelon officers were completely unaware of the atrocities, credible?

6. If such a finding is credible, doesn't it warrant a finding, at the very least, of gross incompetence in respect of those same officers?

7. Was the army culture - for many years debauched by identity politics and virtue-signalling in the same way as the cultures of large corporations, bureaucracies and academic institutions in Australia have been - at least in part responsible for allowing the atrocities to take place?

It is clear, however, that the Australian government and the defence-force elites have no intention of focusing on these issues.

Rather, they will no doubt hope that the never-ending inquiry process will simply drift off into the future, and that the Afghanistan war crimes issue - and, more particularly, their own responsibility for it, together with their inept handling of it - will fade from public consciousness.

This, more likely than not, is precisely what will happen. It is, unfortunately, the way that most contemporary western democracies and the elites that govern them handle such crises, and get away with it.

Graham Hryce, an Australian journalist and former media lawyer, whose work has been published in The Australian, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age, the Sunday Mail, the Spectator and Quadrant.

NINE Aussie soldiers commit suicide as war crimes scandal morphs into shambles, with top brass shielded & squaddies blamed

Canberra failed to deal with atrocities laid bare in a report which found that elite special forces' murder of prisoners and innocent civilians in Afghanistan was "disgraceful." Sadly, the guilty...