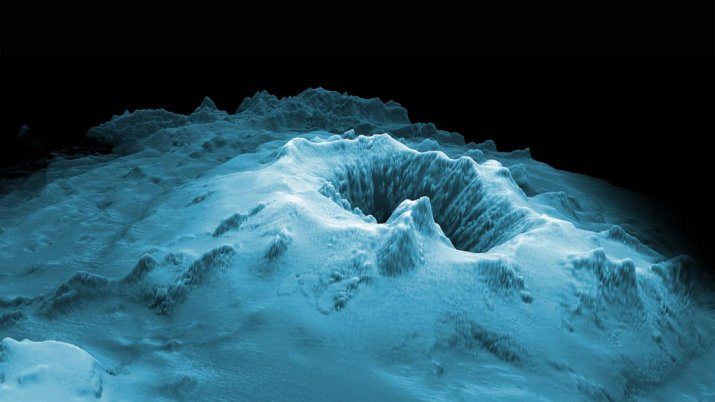

Eager to find out exactly what had happened deep below the sea, scientists from the University of Tasmania in Australia have sent a pair of diving robots to examine the volcano (called Havre) and the surrounding area. The results are a lot of fun: according to volcanologist Rebecca Carey who led the study, "what we found on the seafloor was almost entirely different from what we expected".

Whenever a scientist says that something is the opposite of what they were expecting, you know things are interesting. Throw in a giant underwater volcano, and things get even better.

While the volcano's activity wasn't viewed from up close, thanks to its location at the bottom of the ocean, flotsam from the eruption was visible on satellite images that have been taken from space. From this, in 2015 (three years after the eruption), the scientists were able to pinpoint the location of the volcano, and were able to track how the area had surrounding changed from before things went boom.

Two submarine robots were deployed to examine the area - one searched a wide area of around four kilometers surrounding the volcano, while another was piloted remotely from a nearby ship so that the scientists were able to get up close and personal with the volcano's crater and sites of interest in its near vicinity.

The surprising find? Most of the volcanic material had disappeared. Typically, a volcano will kick up a lot of ash, dust, rock, and of course, lava. This generally stays fairly close to the volcano itself, and can be seen as an indicator of where a volcano has popped.

In this case, though, despite the eruption's enormous size, seventy five percent of the volcanic material that was kicked up had dispersed across a wider area. Around the volcanic crater, there wasn't nearly as much rock as the scientists had expected.

According to Carey, this suggests that our records for a lot of volcanic eruptions could be woefully wrong:

"Now we know that the geological rock record is unfaithful to these very large magnitude powerful events."This is a big deal for the future of volcanic study. The scientists may well have proven that underwater volcanoes behave very differently to those that are above the sea. Alternatively, they could have proven that something is going on with big eruptions that's totally different to what we normally see with relatively subdued volcanic activity.

There's likely going to need to be a lot more tests in the wake of this study, as scientists reevaluate the way they catalogue, record and even predict volcanic eruptions.

We've learned something new and interesting about the way volcanoes work, and it's all thanks to a pair of hard-working robots. And some dedicated satellite photographers, and a bunch of scientists using the best tools that modern technology can provide.

Reader Comments

All the better to control you, my dear.

If the land we see was once submerged then who knows how much evidence is lost