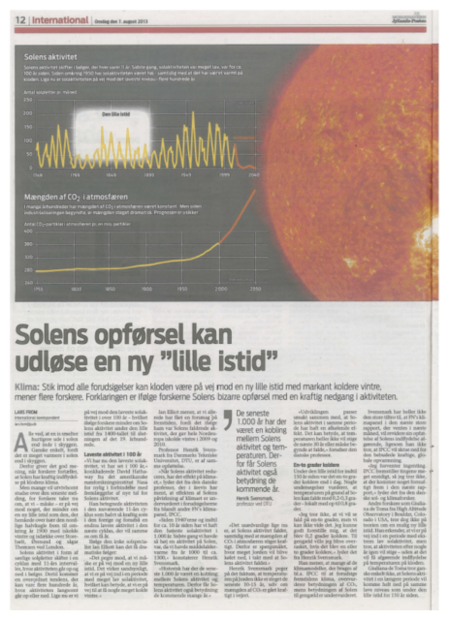

© NoTricksZoneThe August 7 edition of Denmark’s Jyllands-Posten featured a major 2-page article on the globe’s 15-years of missing warming and the potential solar causes and implications.

Another major European media outlet is asking:

Where's the global warming?Moreover, they are featuring prominent skeptic scientists who are warning of a potential little ice age and dismissing CO2 as a major climate driver. And all of this just before the release of the IPCC's 5AR, no less!

Hat-tip: NTZ reader Arne Garbøl

The August 7 print edition of the Danish

Jyllands-Posten, the famous daily that published the "

Muhammad caricatures", features a full 2-page article bearing the headline: "

The behavior of the sun may trigger a new little ice age" followed by the sub-headline: "

Defying all predictions, the globe may be on the road towards a new little ice age with much colder winters."

So now even the once very green Danish media is now spreading the seeds of doubt. So quickly can "settled science" become controversial and hotly disputed. The climate debate is far from over. And when it does end, it looks increasingly as if it'll end in favor of the skeptics.

The

JP writes that "

many will be startled" by the news that a little ice age is a real possibility. Indeed, western citizens have been conditioned to think that nothing except warming is possible. Few have prepared for any other possibility.

In its latest 2-page report, the

JP now appears to tell its readers that our views on climate science have to be much more open minded and unshackled from the chains of dogmatism.

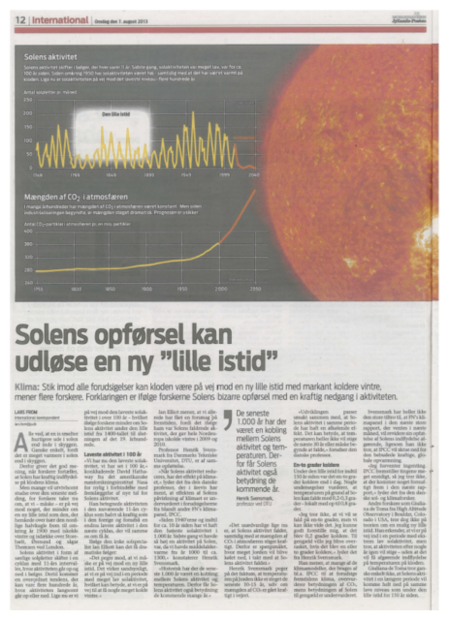

JP starts by reminding readers that it was just over 100 years ago that the world had clawed itself out of the little ice age, which extended from 1400 - 1900, a time when the Thames river often froze over. All paths in determining the cause of the little ice age all seem to converge to a single factor:

solar activity.

Comment: Interesting. Two years ago, this happened:

Chile's Atacama Desert hit with record snowfall

Last year this happened:

Record-breaking blizzards and record-breaking flash-flooding in the 'driest, hottest place on Earth' for three years in a row: Man-made global warming in action... or another sign that we're headed into an Ice Age?