For decades, it was thought that only two types of superconductors existed, but a

new study has just uncovered a third.

© US Department of Energy on Flickr

Wires don't usually like being the bearers of electric current. While we find them extremely

useful to light our houses, charge our phones, and heat water for our tea, they routinely manifest their opposition to the flow of electricity by heating up. Because of this effect, called electrical resistance, the energy dissipated as heat is wasted, and the amount of electric current that a wire can carry before it melts is limited.

But a special kind of material is much happier to host electricity, so much so that under very low temperatures they do not exhibit any resistance.

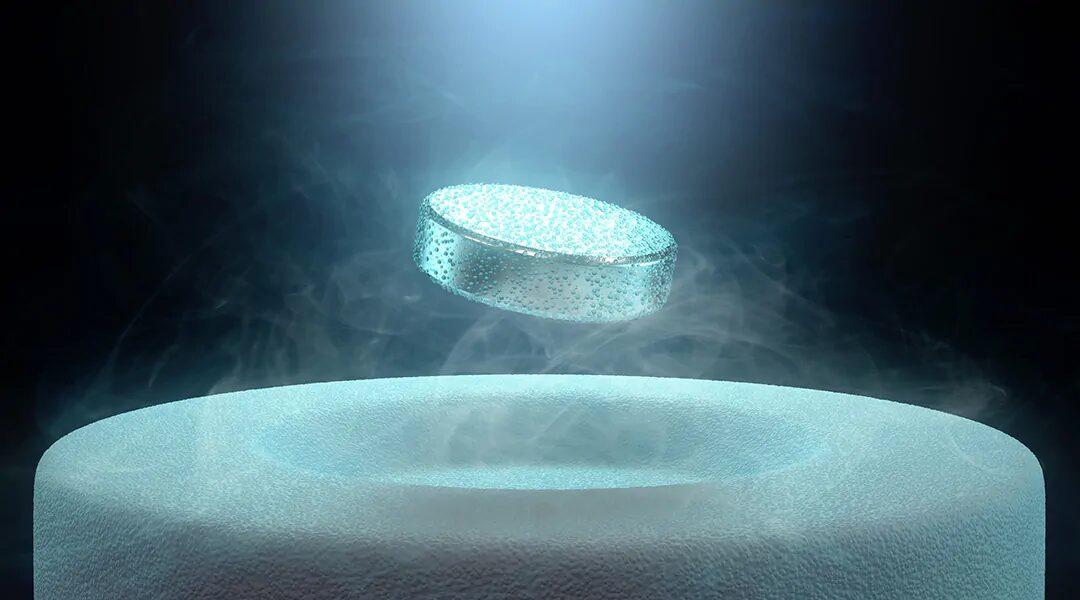

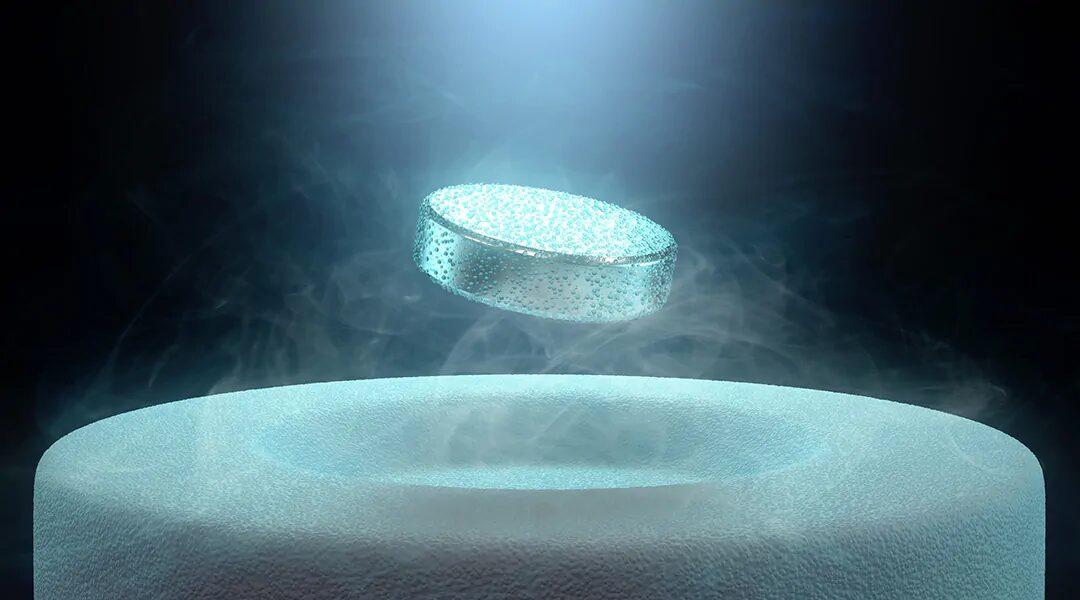

Superconductors, as they are known, don't heat up at all and can thus carry much larger electric currents, which in turn makes them behave as extremely strong magnets. These superconducting magnets are part of MRI scanners, particle accelerators such as the ones at CERN, and the ultra-fast magnetic levitation trains being constructed in Japan, to name a few examples.

Since superconductivity was comprehensively studied in the 1950s, it has been traditionally classified into two main types. But a new paper in

Advanced Science puts forward a third type of superconductivity that was previously only thought to apply to extremely thin layers of materials.

In the study, researchers develop the mathematical equations that describe this

new type of superconductivity in thick, three-dimensional materials, and observe their behavior in the laboratory. The authors suggest that this new mechanism could open a door towards developing room-temperature superconductivity — a "holy grail" in the field.

Comment: