On January 25, the Jerusalem District Planning Committee rejected the residents of Palestinian village al-Walaja's plan to legalize their homes and further develop the community. Instead, the committee declared their land an ancient agricultural area in need of environmental conservation that should be transformed into a national park.

The notion of environmental integrity struck Amy Cohen, director of international relations and advocacy at Israeli non-profit Ir Amim, as contradictory.

"The planning committee and the [Israel] Civil Administration within the West Bank [have] been promoting and advancing plans within the same area for Jewish settlers. It shows massive discrimination in how [Israel] treats Palestinian areas in order to suppress the residential development."The committee's decision paves the way for the lifting of the demolition freeze on 38 al-Walaja homes. On April 26, Israel's Supreme Court will convene for a hearing on al-Walaja's 2018 petition over its resident-initiated outline plan.

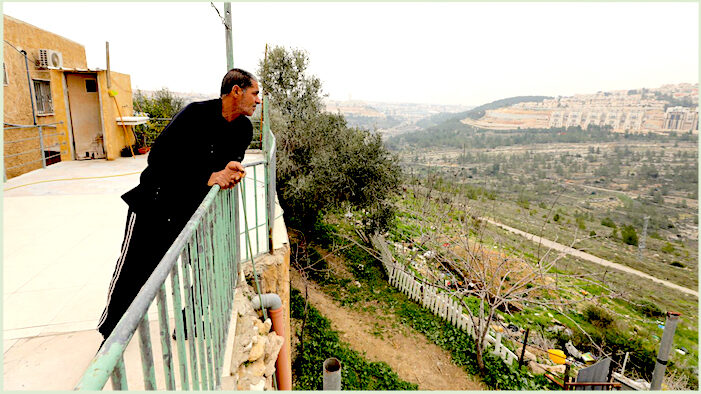

"It's not logical or legal," A'raj said, referring to the Planning Committee's rejection of the development plan for environmental reasons. "The village is surrounded by settlements and the wall, which destroyed the nature and environmental landscape."

The Planning Committee did not respond to requests for comment.

Zones and no permits

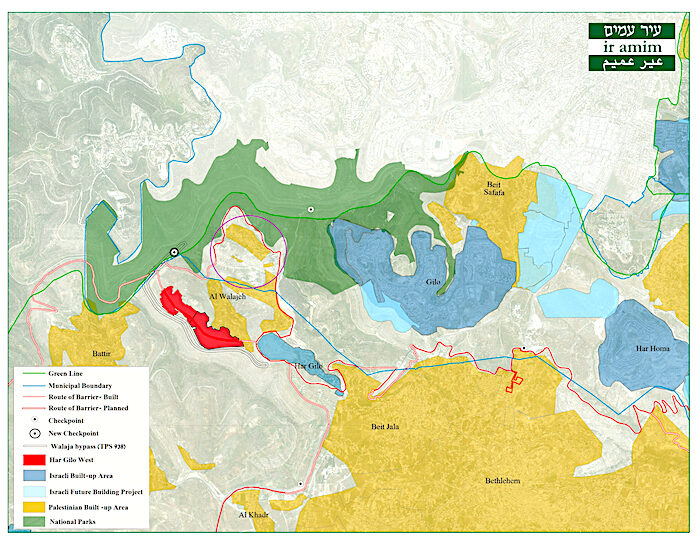

When Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1967, it took the northern section of al-Walaja as well. Today, al-Walaja is split between Jerusalem and Areas B and C of the West Bank, so one-third of the land is controlled by the Jerusalem Municipality and the rest by the Bethlehem Governorate.

The Jerusalem area of al-Walaja has been at risk of forced displacement for a decade as a result of the Planning Committee's refusal to discuss an outline plan. This refusal has made it impossible for the community to obtain building permits, so A'raj had to construct his house without one.

Amid the absence of building permits, demolition orders have increased. More than 20 homes have been razed in al-Walaja since 2016.

An isolated village cut off from its surroundings

Israeli authorities have prevented al-Walaja from developing while expanding Jewish settlements around the village and the apartheid wall (the barrier separating the West Bank and Israel).

Construction of the wall on three sides of al-Walaja cut off the village from nearly 300 acres of its agricultural land and turned that land into Nahal Refaim National Park. Har Gilo settlement lies to the south of al-Walaja. The Israel Civil Administration's proposed expansion of the Har Gilo settlement to the west of the village will extend the wall, thereby enclosing al-Walaja and fully isolating it from its surroundings. The Civil Administration did not respond to requests for comment.

"The wall and the settlements deprived us from accessing our own land that we worked so hard to cultivate," A'raj said, mentioning how the villagers are now blocked from the olive trees they harvested before the wall was built.

Israel’s destruction of ancient terraces to build the wall (right)

"The Civil Administration confiscates our equipment when we start building a new house. The settlers around us use drones to take pictures when we start building and send them to the Civil Administration. The police put checkpoints at the entrance of the village and sometimes inside the village and the Walaja Bypass Road [connecting Har Gilo settlement to Jerusalem] gets a lot of traffic, so it limits our movement."A'raj lamented that if his home is demolished, he will likely leave al-Walaja, the place he's called home his whole life. "It's a huge tyranny that I have to leave my own house and my own land," he said.

Israel doesn't provide alternative or temporary housing for Palestinians whose homes they demolish. Sari Kronish — East Jerusalem planner for Bimkom, an Israeli planning rights organization — described the government's lack of consideration in helping displaced families find housing as one of the "dark sides of the Israeli regime at the moment."

"The very sad reality is that the authorities don't offer [the uprooted Palestinians] anything. They just treat them as lawbreakers who are receiving their penalty. People just become homeless and become displaced."Ir Amim's Cohen emphasizes that what Israel is enacting isn't just the wide-scale displacement of Palestinians but also an attempt at annexation. She elaborated:

"It's an acute humanitarian toll that's exacted upon the families, but it is also in service to the Israeli objective of consolidating control, which completely undermines any sort of conditions for a two-state solution based on two capitals. Because if you can completely segment Palestinian contiguity and advance steps toward de facto annexation of these areas, then you're foiling a prospect of an agreed resolution."Not just al-Walaja

In what many Palestinians have described as a continuation of the Nakba (Israel's 1948 ethnic cleansing campaign in Palestine), Israel is currently in the process of expelling thousands of Palestinians from East Jerusalem under the pretext of preservation.

"More and more open areas in East Jerusalem are being designated as preservation or national parks, and this is clearly in order to prevent Palestinian urban development," Kronish said.

In the Al-Bustan neighborhood of the East Jerusalem district of Silwan, mass dispossession looms over the residents in order to make room for the touristic venture, Garden of the King. The community of Sheikh Jarrah is experiencing displacement at the hands of settler groups for the Shimon HaTzadik National Park.

Israel has long employed the practice of stealing Palestinian land and claiming it for recreational purposes. Many of Israel's prized national parks were built on top of Palestinian villages destroyed during the Nakba. In Jerusalem, for instance, the remains of the village of Lifta are now a national park and hotel. Garbage and graffiti adorn what's left of Lifta's stone houses. Most of the village's inhabitants, who were expelled in 1948, and their descendants live in refugee camps around Jerusalem — unable to return to home.

"It's a form of institutional confiscation and settlement in the guise of green protection," Kronish said.

Displacing indigenous peoples under the claim of conservation is an inherently settler-colonialist tactic spanning regions and centuries. Most well-known national parks in the United States like Yellowstone and Yosemite were once Native American tribal territories. In order to create an "uninhabited wilderness," the federal government first had to remove the native peoples living on that land.

Modern environmentalism ignorantly dictates: Some environmentalist assumptions suggest humans cannot coexist with wildlife. But that racist assumption idea ignores the history of indigenous communities living with and preserving nature.

Native Americans understood how to sustainably tend to the land. And just as in al-Walaja, maintaining the land is part of their livelihood. Kronish explained:

"This type of agricultural lifestyle is very dependent on people living [on] and working the land harmoniously. Once people are displaced, attempts at preservation become artificial. The residents would argue that by continuing to live there, they are more able to continue to preserve. For them, it's not a question of preservation. It's a question of a way of life and connection to the land."

About the Author:

Jessica Buxbaum is a Jerusalem-based journalist for MintPress News covering Palestine, Israel, and Syria. Her work has been featured in Middle East Eye, The New Arab and Gulf News.

RC

*I HATE having to do this: "I hereby expressly disclaim any rights, such as copyright, trademark, et al. without limitation, to the above words/ phrasing, what the f. ever. I wish for you to own it free and clear.

rc