It's a regular stop for holidaymakers in Israel. American teenagers, some of them boys in sleeveless basketball tops, cluster on hilltop lookouts in the Golan Heights, a volcanic plateau captured from Syria half a century ago. Visitors ride quad bikes along dusty paths or spend the day touring the area's vineyards. Signs on the roads warn of the risks to tourists: "Caution - cyclists ahead."

For Syrians on the other side of a fortified perimeter fence, there are more pressing concerns. Thousands have gathered as close to the border as possible, gambling their lives on the assumption that Syrian government forces fighting rebels will not bring the battle too close to Israel.

It is no sure bet. From the Israeli-controlled side, the whistle of an unseen jet could be heard and then a sudden, deeper rumble. In the distance, a grey pillar of smoke punched hundreds of metres into the air as the airstrike hit.

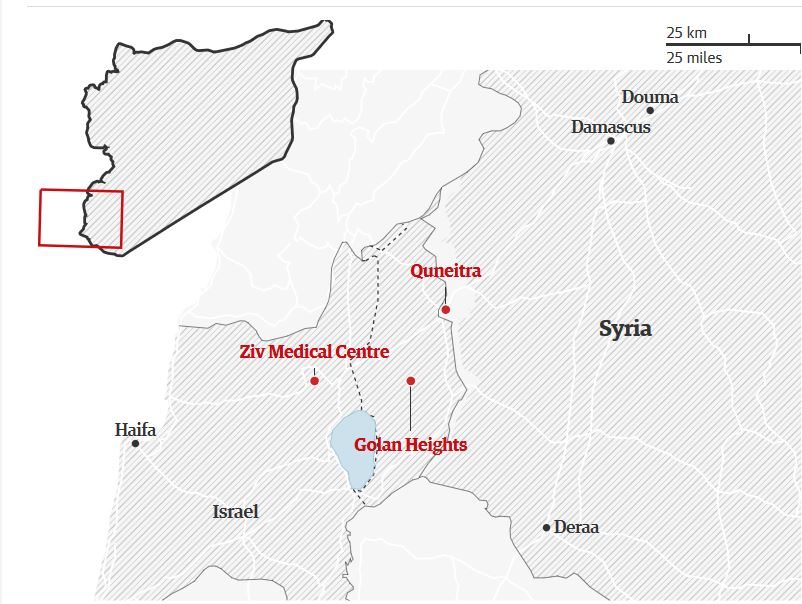

In a push to retake one of the last insurgent holdouts in Syria's seven-year civil war, clashes in the southern Deraa and Quneitra regions erupted last June. On Friday, there were signals that a deal had been reached with militant groups to hand over territory, but it was unclear if the offensive would stop altogether.

Refugees have set up tents just metres away from the Israeli-controlled Golan frontier, and early last week dozens risked walking over minefields to approach the border fence, some carrying white flags in an apparent attempt to cross to safety. They were told to go back by Israeli border guards.

A humanitarian worker in Quneitra said the situation at the camps has been difficult, with no toilets and limited medical supplies.

"The people from the camps were approaching the fence ... to seek protection because the bombardment was very close," he said.

"The truth is that people sought refuge with the Israelis to protect them from the [Syrian] regime's violence. People were extremely nervous because most of them are opponents of the regime and have been surrounded from all sides. It was truly tragic and frightening."

"There was a major attack by warplanes. The numbers in Quneitra were very large, and the humanitarian situation was very difficult. There are no homes, people were staying in tents, and they were lucky if they found tents."

South-west Syria is of vital importance to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, and not only strategically. Backed by Russian forces, the army hoisted the national flag in the city of Deraa this month, a deeply symbolic victory as it was there that the pro-democracy uprising first erupted in 2011 before a bloody response by security forces turned it into a war.

The displaced are trapped at the edges of this corner of Syria, where three countries meet. Jordan, to the south, says it already hosts more than a million displaced people and cannot accommodate any more. Israel, too, has said it will not allow any refugees to cross, despite urgent calls by humanitarian agencies saying their safety is at risk. Part of its refusal is an unwillingness to tip a demographic balance in a majority Jewish state, where about a fifth of the population is Arab.

Comment: And that sentiment trumps all humanity.

Apartheid: Israeli Knesset passes law declaring itself Jewish-nation state and describing Jewish settlements as national interest

"We will continue defending our borders, we will provide humanitarian aid as best as we can, we will not allow entry to our territories," Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said this month.

However, a few thousand people have been allowed by the army to enter Israel during the war, albeit on a temporary basis. At the Ziv Medical Centre in northern Israel, up to half of the intensive care beds are occupied by Syrians, many of them with blast and bullet wounds.

One 14-year-old boy, from an area close to the Israeli frontier, had most of his right thigh blown off two months ago and was brought to the hospital by his mother, who contacted the Israeli army in the middle of the night. His social worker, an Arab citizen of Israel, Faris Issa, said the teenager did not speak for the first few weeks. "Most patients who arrive from Syria, they sleep for the first month. They are so tired," he said.

Issa says he tries not to push potentially traumatised patients to engage, often giving them a week or so in recovery before conversing. He suspects many are rebel fighters - most are adult males - but it is hospital policy not to ask.

The programme remains a delicate issue. Israel's annexation of the Golan Heights was not recognised internationally and it remains in a state of war with Syria, meaning Syrians who seek Israeli treatment are at risk when they go back. Ziv hospital makes sure not to identify them, and discharge papers are written in Arabic and English, with no visible Hebrew.

The injured 14-year-old boy is recovering but he has lost about a tenth of his right leg. Doctors say he needs another month or so. Meanwhile, his thigh remains in a metal casing. "I want to go back home walking," he said, smiling.

The hospital's senior paediatrician is also of Syrian descent, but his family is from the minority Jewish population who left years ago, and he has never been there. "For the first two years of the war, Israel did nothing," said Michael Harari, 63, who speaks enough Arabic to converse with his patients. "On a daily basis, you could hear the civil war being enacted. It was a terrible feeling."

That changed one night in 2013 when the army arrived unannounced with seven wounded Syrians. Since then there has been a steady influx, and Harari has been treating war wounded as well as children with unrelated chronic issues. The hospital has delivered 12 Syrian babies.

Harari said the recent offensive was not yet reflected in the number of patients arriving, possibly because the fighting was focused away from the frontier. But he added: "It's possible that the pocket is closing in ... We're always prepared. We're on perpetual standby."

Comment: If Israel claims the territory then why aren't they taking these people in? Apparently they view the responsibility the same way they view the West Bank and Gaza.