But it will take the outcome of scientific analysis on the almost 800 people whose remains were found in the excavation to reveal the complete story of the ringfort.

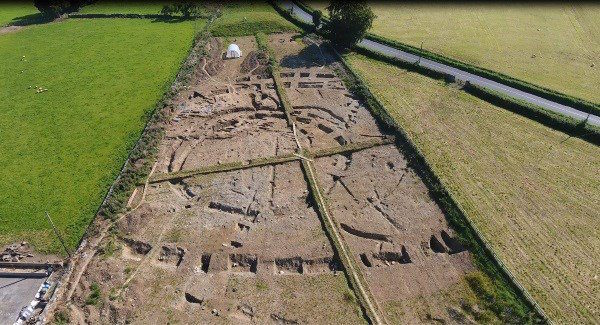

With no previous record of any habitation on the site, about a mile north of Roscommon town, it was only when geophysics testing results came back that it was clear that there were significant archaeological features.

After a year-long excavation that ended last October, including work by archaeologists through some of the worst storms in decades, a picture is emerging of the settlement that was probably occupied between the sixth and 11th centuries.

The remains of 793 people were found, about three quarters of them were intact and the others were disarticulated. The dating techniques to be used during the analysis work over the next 15 months should confirm the period of occupation.

What is already evident from the excavation, carried out under the direction of Shane Delaney, is that the site was probably not inhabited in its later period of use. Instead, it may have been more of an administrative and industrial hub for a community living in a series of ringforts in the surrounding area.

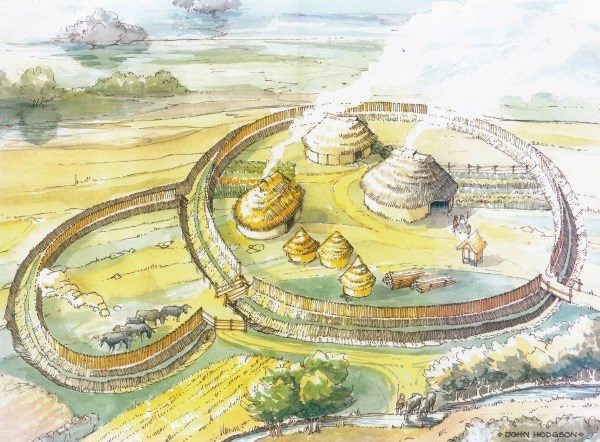

The earliest ringfort enclosure at the site was about 40m in diameter, but there was no evidence on any maps or in local folklore to suggest any significance before the site was tested by archaeologists. One theory is that it might have been levelled over centuries of ploughing for agriculture, or cleared during the landscaping of an area of parkland for the nearby Ranelagh House in the early 1700s.

According to Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) project archaeologist Martin Jones, overseeing the work as part of a road realignment on the N61, there are at least three other ringforts within 500m.

"The working theory is that this was originally inhabited by a family that rose to some relative prominence in the area. They may have then constructed a number of other ringforts around this one, which became a centre for industrial activity," he said.

This is supported by the lack of evidence of structures within the excavation site, and the wealth of artifacts suggestive of light metalwork industry.

The amount of unfinished jewellery pieces found by the archaeologists indicates they were being made in a workshop at the site, possibly for trade.

The jewellery items and fragments found, some of them associated with the burials, include amber and jet beads, a lignite bracelet and a brooch panel with enamel stud. A fragment of a copper alloy bracelet has been dated by its decoration to around AD350 to 550.

The ringfort's use may also have switched from human settlement to raising and slaughtering animals, evidenced by the substantial number of bones found across the site. A set of iron shears in a range of sizes indicates processing of animal wools.

The believed high status of the family, which may have been using the ringfort as a hub for food production, is also hinted by a copper alloy toe-ring on one of the burials, possibly the remains of a man. This is believed to have been part of a sole sandal, a burial rite associated with elevated status in the period in question.

The number of burials puts the site at the larger end of the scale for such locations, Mr Jones said.

However, radiocarbon dating results are awaited to determine how many relate to the period the site was in active use.

The understanding from evidence gathered to date is that, while the original family may have moved out and built other ringforts nearby as it expanded over several hundred years, the main enclosure continued to be used for burials.

The DNA testing and other analysis of the human remains should also clarify the timeline of the ringfort's use, but it appears that it was occupied during early Christianity period.

A monastery was founded in Roscommon by St Comán in the early 500s, and had become quite important by the eighth century.

A feature in a number of graves in the burial ground excavated for TII was the placement of items with the body, in many cases apparently hidden under the hair. The artifacts found in such positions included beads, blades, a bracelet fragment, and copper and bone pins.

"Local society was still finding it difficult to let go of older pre-Christian customs," suggested excavation director Shane Delaney.

A small number of crouched burials were found, with their knees pushed up to their chest, possibly suggesting these were non-locals being buried according to their own traditions.

Others have signs of punishment or disrespect, including at least two in which feet and hands may have been bound, one of them buried face down. Two of those buried at the Ranelagh excavation site were decapitated, and several children or adolescents were placed in the ground in embracing positions.

The discovery of a young adolescent buried with worked antler placed on their hands, which were clasped over the pelvis, could also add to knowledge of medieval burial rites. It is one of a handful of such burials recorded in Ireland, where there was a deliberate inclusion of antler, possibly a symbol of regeneration.

With the excavation works now completed, the analysis of the artefacts and human remains will help to piece together an even clearer picture of the site's history. DNA testing, for example, will tell the relationships between the individual skeletons.

Other tests which are planned to begin soon will use the latest techniques to offer further evidence, such as the diets of the people buried at Ranelagh, and their geographical origins.

"When we have the results of radiocarbon dating and all the other analysis, we will have a huge amount of additional information. That's when the real detective work begins," said Mr Jones.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter