Once the subject of dystopian science fiction novels, three emerging technologies served as a focal point for a new survey to glean the public's willingness to accept what many would call exceedingly invasive biomedical 'enhancements.'

Pew Research Center surveyed 4,726 adults — 47 of whom additionally agreed to participate in focus groups — to discern not only how well putative biomedical advancements might be received, but where the public stands on inherent ethical and moral questions arising from their use.

Given previous trepidations and warnings from government whistleblowers such technology could easily be employed for less than benevolent purposes, results proved a startling level of both acceptance and eagerness.

Keep in mind, every one of these technologies, while not yet widely available for elective use, are actively being developed — and though the majority of those surveyed expressed reservations for their use in otherwise healthy people, a significant number essentially said, 'sign me up.'

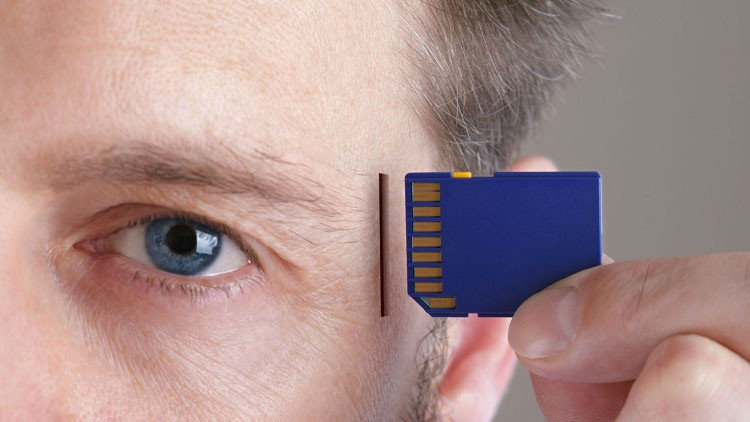

Though 69 percent of respondents claimed they would be "worried" about an implant — known as a neuroprosthesis — to improve cognitive abilities, fully 34 percent said they were "enthusiastic" about the idea. Largely divided along religious lines, many felt such invasive technology to improve the ability to think and process information would cross the line of "meddling" too much with nature.

But of the three biomedical 'improvements' in question, a microchip brain implant was perhaps the least Orwellian — as well as the least accepted.

As Pew reported:

"New developments in biochemistry are creating the possibility of using a synthetic blood substitute (sometimes referred to as 'superblood'[!!!]) to significantly boost people's oxygen levels in the bloodstream. With the synthetic blood substitute, a higher concentration of oxygen would be carried from the lungs to the muscles through the bloodstream and could significantly improve an individual's physical speed, strength and stamina. This, in turn, could allow people to function in extreme conditions, or to simply perform everyday tasks with greater ease."Less people, 62 percent, remained skeptical or distrusting of such technology than of neuroprostheses, while a greater number, 37 percent, were at least "somewhat enthusiastic" about its possibilities.

"Right now, this man-made substitute for blood is being developed for people with some kind of illness or medical condition," Pew explained. "But in the future, a transfusion with this kind of synthetic blood substitute could be developed for use by healthy individuals ..."

But the biomedical advancement garnering the most enthusiasm would not concern any of the adults surveyed — but would be performed on children.

Gene editing to greatly reduce babies' risks for developing various diseases later in life found just under half of respondents, 49 percent, at least somewhat enthusiastic about the prospect.

"The potential genetic modification of humans and its ramifications have long been debated, but a recent scientific breakthrough in gene editing — a technique known as CRISPR — has raised the urgency of this conversation," Pew explained, noting currently such technology isn't used in this manner.

"While many Americans say they would want to use such a technology for their own children, there is also considerable wariness when it comes to gene editing, especially among parents of minor children."Again, though divided by respondents' religious affiliation, the number of people who would accept what could be considered a modernized, euphemized version of post-birth eugenics is rather jarring.

As an ethical question — whether or not such gene editing would go too far — Americans remain split.

"The survey asked respondents whether the idea of editing genes to give healthy babies a much-reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions is in keeping with other ways that humans have always tried to better themselves or whether 'this idea is meddling with nature and crosses a line we should not cross.' Americans' judgments on this question are closely divided, with 51% saying this idea is no different than other ways humans try to better themselves and 46% saying this idea crosses a line."These advancements in technology can and will benefit humanity and there are certainly places for them in society. That being said, however, when the state is involved, things can turn sour quickly.

Critical ethical questions must be raised when it comes to elective biomedical 'enhancements' of otherwise healthy individuals and their children, before the market explodes with technologies wrapped in positive packages for which no one considers potential future ramifications.

Imagine our current epidemic of police violence in the context of officers who've elected to receive synthetic "super blood" to enhance stamina, strength, and speed — particularly if civilians remain reluctant to receive the treatment. And while increasing the efficiency of oxygen circulation might appear innocuous, possible unknown side effects — such as which occur with steroids or hormone treatment — must be fully investigated before synthetic blood is widely used.

Gene editing, though employed presently with success for various conditions, in the case of healthy children might have ramifications which couldn't be foreseen.

"Developments in biomedical technologies are accelerating rapidly, raising new societal debates about how we will use these technologies and what uses are appropriate," said lead author and associate director of research at Pew, Cary Funk, in a statement cited by UPI. "This study suggests that Americans are largely cautious about using emerging technologies in ways that push human capacities beyond what's been possible before."Though Pew did not broach the topic of potential governmental involvement, it would be curious to find whether the same people who expressed enthusiasm would feel the same if such tech somehow became mandatory — or, perhaps worse, was employed surreptitiously as has been the case with advancements in domestic surveillance.

As a 59-year-old Atlanta woman keenly, but reservedly, warned,

"If it starts to sound Hitler-like, [trying to create] a perfect specimen of man and woman ... then people who are not perfect might be treated badly."

If they are enthusiastic about it, they likely don't have enough thinking power for it to work in the first place.