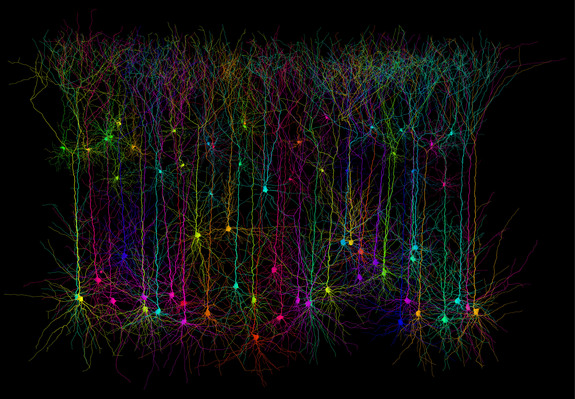

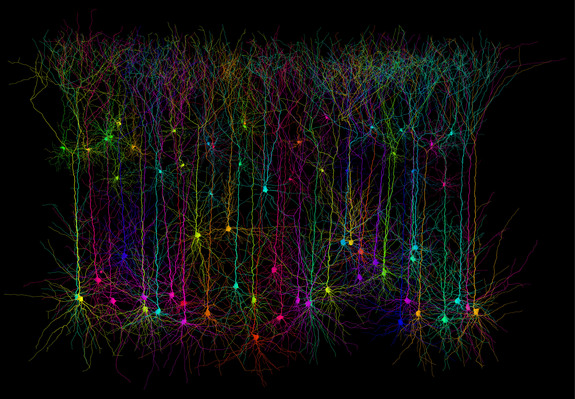

© UCLHere computer-simulated images of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex, revealing branching dendrites now shown to carry out sophisticated computations rather than just acting as passive wiring.

The brain may be an even more powerful computer than before thought - microscopic branches of brain cells that were once thought to basically serve as mere wiring may actually behave as minicomputers, researchers say.

The most powerful computer known is the brain. The

human brain possesses about 100 billion neurons with roughly 1 quadrillion - 1 million billion - connections known as synapses wiring these cells together.

Neurons each act like a relay station for electrical signals. The heart of each neuron is called the soma - a single thin cablelike fiber known as the axon that sticks out of the soma carries nerve signals away from the neuron, while many shorter branches called dendrites that project from the other end of the soma carry nerve signals to the neuron.

Now scientists find dendrites may be more than passive wiring; in fact, they may actively process information.

"Suddenly, it's as if the processing power of the brain is much greater than we had originally thought," study lead author Spencer Smith, a neuroscientist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,said in a statement.