What's more, people who score high on a personality trait called resilience -- the ability to adjust to environmental change -- had the highest amount of natural painkiller activation.

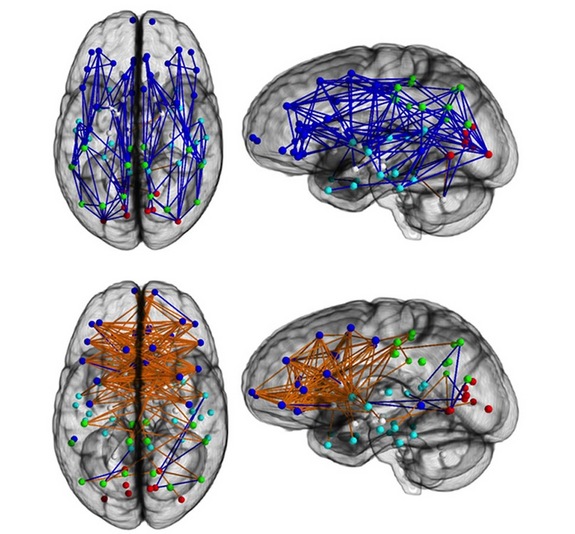

The team, based at U-M's Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute, used an innovative approach to make its findings. They combined advanced brain scanning that can track chemical release in the brain with a model of social rejection based on online dating. The work was funded by the U-M Depression Center, the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, the Phil F Jenkins Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

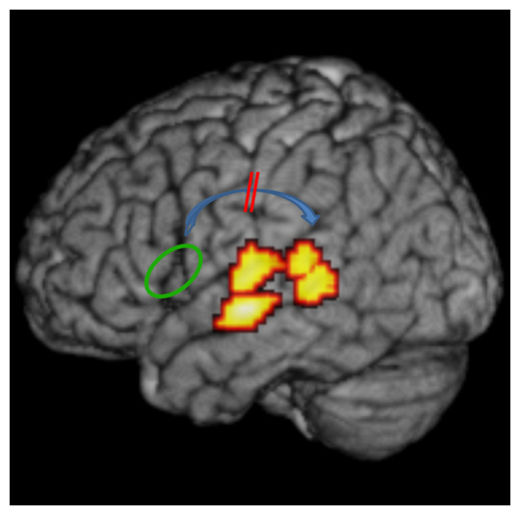

They focused on the mu-opioid receptor system in the brain -- the same system that the team has studied for years in relation to response to physical pain. Over more than a decade, U-M work has shown that when a person feels physical pain, their brains release chemicals called opioids into the space between neurons, dampening pain signals.

Comment: See also: The smell of fear can be inherited, scientists prove