The estimates, carried out for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), described "increasing, intensifying" levels of extreme poverty experienced by some of the country's poorest households in recent years, and highlight a social security system increasingly failing to protect society's most vulnerable.

Cuts in social security rates over the past decade, together with design flaws in universal credit and disability benefits, as well as the harsh impact of welfare reforms such as benefit caps, were driving sharp rises in extreme poverty even before Covid struck, the study says.

Destitution was most salient in areas of the north-east and north-west of England, and parts of inner London. Over one in every 100 households in Blackpool, Kingston upon Hull, Liverpool, Manchester, Middlesbrough, Newcastle upon Tyne, Nottingham and Salford were in extreme poverty.

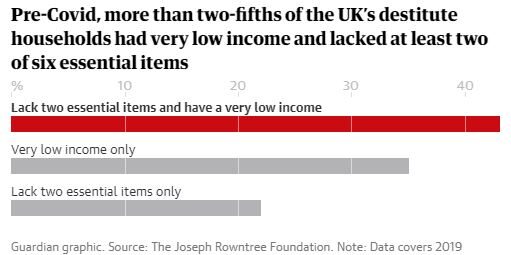

The study defines destitution as inability to afford two or more of shelter, food, heating, lighting, weather-appropriate clothing, or basic toiletries over the past month, or a weekly income after housing costs of or below £70 for a single adult or £145 for a couple with two children.

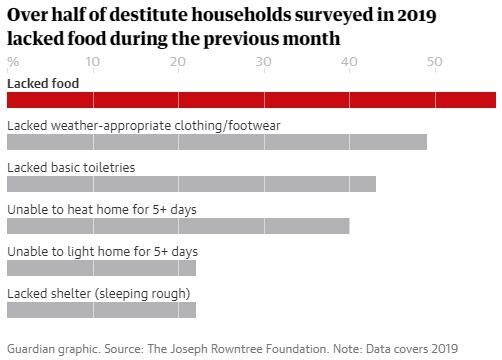

Over half of destitute individuals most commonly lacked food, followed by suitable clothing (49%) and basic toiletries (43%). A third of destitute households reported no income at all. While single people were most likely to be destitute, families - especially lone mothers - were increasingly at risk, the study said.

Helen Barnard, director of JRF, said: "Our social security system should act as an anchor to hold us steady when we're pulled down by powerful currents like job loss, illness or relationship breakdown. But, right now, our system is not doing enough to protect people from destitution."

She added: "It is appalling that so many people are going through this distressing and degrading experience, and we should not tolerate it. No one in our society should be unable to afford to eat or keep clean and sheltered. We can and must do more."

The research was carried out by the Institute for Social Policy, Housing, Equalities Research at Heriot-Watt University, its third such study since 2015. Around 1m households experienced destitution in 2019, up 35% since 2017, equivalent to 2.4 million people. These rates were likely to have doubled in recent months, it said.

The report will pile the pressure on ministers to commit to maintaining the £20 a week universal credit boost in April - it says it will decide in the new year. But it also highlights long-term concerns over the adequacy of the UK social security system after a decade of austerity and with months of economic recession lying ahead.

A government spokesperson said: "Making sure every child gets the best start in life is central to our efforts to level up opportunity across the country, which is why we have raised the living wage for all and boosted welfare support by billions, including £170m to help families stay warm and well-fed over Christmas."

Although it welcomed the government's pandemic measures, including the temporary £20 a week uplift, the study said these were not enough to prevent some people falling into destitution, and the problem of extreme poverty would accelerate if the benefits top-up was not maintained.

The underlying fragility of the welfare system was highlighted by the finding that half of destitute households in 2019 were in receipt of universal credit or had applied for it. The need to repay advance loans taken out to tide them through the five-week delay for a first benefit payment often left people with little to live on, the report said.

It was striking how Britain was increasingly reliant on charity food banks as a "core welfare response" to growing poverty destitution, the report said. "It seems unwise to rely on this voluntary effort to ensure that the basic physiological needs of large numbers of UK residents are met."

Although around one in five destitute people have complex needs such as homelessness, or drug and alcohol problems, most do not. One in seven destitute people were in insecure work or on zero-hours contracts. Over half (54%) of people in extreme poverty had a chronic health problem or disability.

Migrants, many ineligible for welfare support, were disproportionately likely to be destitute. "That all those present on UK soil during a national (global) health emergency should have access to the basic essentials for survival is the minimum that a rich and human society should undertake to ensure," the study concluded.

The shadow work and pensions secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, said: "No child in Britain should be hungry or without essentials. The government must do more to support struggling families who are facing real hardship this winter. They must see sense and scrap the planned cut to universal credit, which will take £20 a week from 6 million families".

More poor people, more demand for government handouts and socialism, and more steam for the Great Reset engine. Or so goes the plan ...