Some discoveries are just serendipity. Several years ago, U.S. Geological Survey seismologists at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory and Alaska Volcano Observatory were trying out a new method to track seismicity at Kilauea Volcano. The method scans 24-hour sections of seismometer data looking for signal similarity on many instruments. Out of curiosity, they decided to look at the rest of the Island of Hawaii to see what else they might find.

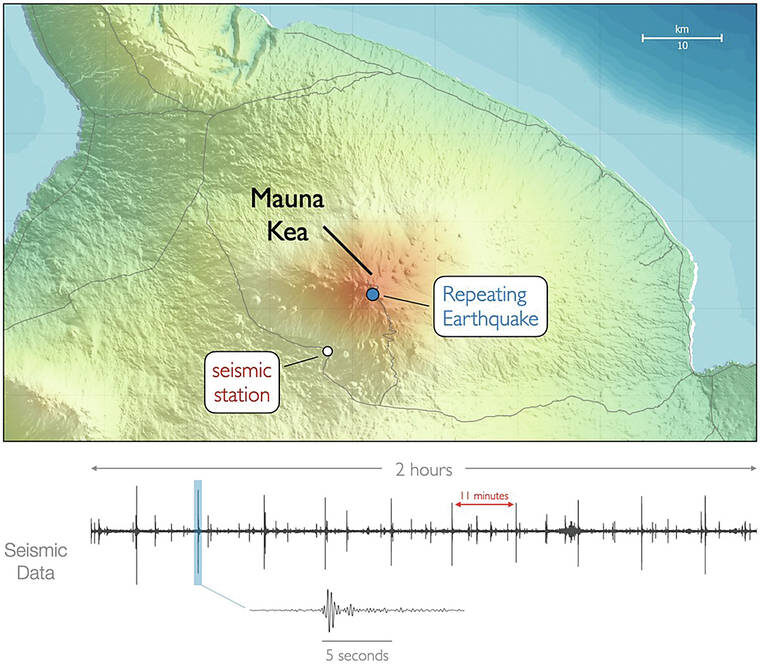

What they found came as a surprise. A study published in the journal Science in May, 2020 describes how they detected deep earthquakes beneath Maunakea that repeat every 7-12 minutes. Noise in the seismic records from wind and nearby cars, together with the small size of the individual earthquakes (magnitude 1.5), had prevented these earthquakes from being detected with the regular earthquake detection system.

The small, repeating earthquakes occur at depths of about 20-25 km (12-15 mi) directly beneath Maunakea's summit and happen every 7-12 minutes with surprising regularity. Furthermore, the repeating events can be detected going back to at least 1999. This was when a particularly quiet seismic station was installed in the saddle between Maunakea and Mauna Loa. It is very likely that the repeating earthquakes were occurring even further back in time.

Scientists were initially cautious to interpret the earthquakes as due to volcanic processes, because the regularity seemed man-made. It took a long period of investigation to rule out all of the possibilities, such as activity at the Pohakuloa Training Area or road construction. But eventually it became clear that these earthquakes were telling us something important about Maunakea.

One clue to the origin of the repeating, deep Maunakea earthquakes is that their seismic waves (or waveforms) look different from those of ordinary earthquakes. Where regular earthquakes produce more high frequency shaking, the Maunakea events are more drawn out, containing lower frequencies. This implies that regular slip on a fault is not responsible for the deep Maunakea events.

Low-frequency earthquakes aren't unusual at volcanoes, but there's no other example of this kind of repetition or longevity anywhere in the world. Ultimately over 1 million earthquakes were found from 1999-2018. Summing the energy release of the earthquakes gives a total that is equivalent to a magnitude-3 earthquake under Maunakea every day.

Adding together the signals of thousands of these earthquakes allows the waveform to be examined in greater detail, and the results suggest the events are caused by the movement of fluids above a deep magma chamber. As the fluids ascend, they enter a crack that is sealed at the top. The continuous flow of fluid will pressurize the crack, eventually breaking the top seal and creating the earthquake. The crack then reseals, and everything starts over again.

So where do these fluids come from? To get earthquakes every 7-12 minutes for decades requires a near-constant supply of fluids. The source is likely magmatic gases that behave like fluids when they are deep within the Earth's crust. These gases separate from the magma as it cools. Large magma bodies cool over hundreds to thousands of years, so this process provides a long-term, nearly continuous supply of fluids to repeatedly drive deep earthquakes beneath Maunakea.

Under this interpretation, the fluids are produced from magma cooling in place. There is no evidence (from this study or other work) that magma is rising under Maunakea. So while this study provides important insight into processes beneath the volcano, it does not change estimates of volcanic hazard at Maunakea. We expect any opening of a new conduit will be accompanied by swarms of shallow earthquakes to provide advanced warning of impending eruptive activity.

The earthquakes nonetheless underscore that Maunakea is classified as an active volcano. Although interpretations can change with new data, the deep low-frequency earthquakes likely serve as a reminder that there is still magma down there, just chillin'.

Volcano activity updates

Kilauea Volcano is not erupting. Its USGS Volcano Alert level remains at NORMAL (https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/vhp/about_alerts.html). Kilauea updates are issued monthly.

Kilauea monitoring data for the past month show variable but typical rates of seismicity and ground deformation, low rates of sulfur dioxide emissions, and only minor geologic changes since the end of eruptive activity in September 2018. The water lake at the bottom of Halema'uma'u continues to slowly expand and deepen. For the most current information on the lake, see https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/Kilauea/summit_water_resources.html

Mauna Loa is not erupting and remains at Volcano Alert Level ADVISORY. This alert level does not mean that an eruption is imminent or that progression to eruption from current level of unrest is certain. Mauna Loa updates are issued weekly.

This past week, about 63 small-magnitude earthquakes were recorded beneath the upper-elevations of Mauna Loa; most of these occurred at shallow depths of less than 8 kilometers (~5 miles). Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements show long-term slowly increasing summit inflation, consistent with magma supply to the volcano's shallow storage system. Gas concentrations and fumarole temperatures as measured at both Sulphur Cone and the summit remain stable. Webcams show no changes to the landscape. For more information on current monitoring of Mauna Loa Volcano, see: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mauna_loa/monitoring_summary.html.

No felt earthquakes were reported in the Hawaiian islands during the past week.

HVO continues to closely monitor both Kilauea and Mauna Loa for any signs of increased activity.

Comment: See also: