© Liran Samuni/ Taï Chimpanzee Project

There are behavioural differences, on average, between the sexes - few would dispute that. Where the debate rages is over how much these differences are the result of social pressures versus being rooted in our biology (the answer often is that there is a complex interaction between the two).

For example, when differences are observed between girls and boys, such as in

preferences for play, one possibility is that this is partly or wholly because of the contrasting ways that girls and boys are influenced by their peers, parents and other adults (because of the ideas they have about how the sexes ought to behave).

Studying non-human primates allows us to identity sex differences in behavior that can't be due to human culture and gender beliefs.Learning more about the biological roots of behavioural sex differences should not be used as an excuse for harmful stereotyping or discrimination, but it can help us better understand our human nature and the part that evolved sex differences play in some of the most important issues that affect our lives, including around diversity, relationships, mental health, crime and education.

Earlier this year, as part of a special issue of the

Journal of Neuroscience Research - titled "An Issue Whose Time Has Come: Sex/Gender Influences on Nervous System Function" -

Elizabeth Lonsdorf at Franklin and Marshall College published

a useful mini-review detailing some of the sex differences observed among monkey and ape infants and juveniles.

"Many sex differences in behavioral development exist in nonhuman primates," she writes,

"despite a comparative lack of sex-biased treatment by mothers and other social partners". Here is a digested account of five of these behavioural sex differences:

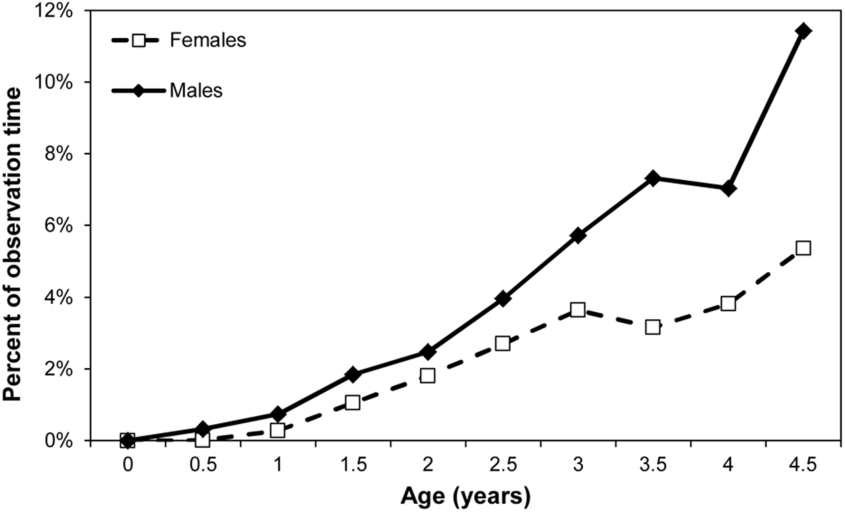

Boy chimps spend more time away from their mothers

Graph shows time spent travelling independently by age for males and females

In human cultures across the world,

boys tend to spend more time away from their mothers as compared with girls, which may reflect an early tendency toward greater risk taking. The same is true in chimps. For a 2014 paper, Lonsdorf and her colleagues, including famed zoologist Jane Goodall, conducted

the most detailed ever analysis of the development of wild chimpanzees, observing 40 chimps from birth to age 5. They found that, by age 3, male infants showed greater physical distance from their mothers than females. The males began moving about on their own earlier than females and covered more distances independently. These and other findings from the study "suggest that

some biologically based sex differences in behavior may have been present in the common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans, and operated independently from the influences of modern sex-biased parental behavior and gender socialization," the researchers said.

Baby girl monkeys are more socialIn humans, girls tend to show more precocious social interest and development than boys. For example, at less than two-days old,

girls spend more time than boys looking at a human face than at a mechanical toy. Though a replication attempt of this specific finding for humans is needed, a very similar pattern has been found in rhesus macaque monkeys. For

a paper published last year a research team led by Elizabeth Simpson observed 48 two- to three-week old monkeys as they were presented with videos of a macaque monkey face. The females spent more time looking at the videos than males and they later displayed more social behaviour toward a human. "In sum, converging evidence from humans and monkeys suggests that

female infants are more social than males in the first weeks of life, and that such differences may arise independent of postnatal experience," the researchers said.

Boy monkeys enjoy more rough and tumbleIn human children, average sex differences in

play preferences are among the most striking, consistent (and controversial) behavioural contrasts found between boys and girls. It never seems to take very long for little boys to pick up sticks and pretend that they are armed with a sword. In contrast, girls typically spend more time pretending to nurture toy dolls or similar. Of course, many say this simply reflects the way that boys are raised to be more aggressive and girls more nurturing. And yet

very similar sex-linked play preferences are seen in our primate cousins.For instance, Gillian Brown and Alan Dixson

studied 34 macaque monkeys for the first six months of their lives and found that the males (filled circles in the graph on the left) engaged in more rough and tumble play than females, including wrestling, pinning down, as well as chasing and gentle hitting. Males also initiated play more often than females. In her review, Lonsdorf notes that similar findings have been observed in blue monkeys, patas monkeys, Japanese macaques and olive baboons.

Girl monkeys spend more time playing parentHuman boys, on average, are less interested than girls in babies. There's a

similar pattern among non-human primates. Observational research at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center with one-year-old Rhesus Macaque monkeys found that the females spent significantly more time than the males with infants. "The focus of young females' attention on infants has been suggested to be important for the development of later maternal skills," the researchers said. They noted that a similar observation has been found for another species: "Juvenile female vervet monkeys that live in the wild carry and cuddle small infants, an experience that may provide them with the motor skills necessary for later matemal behavior, as weIl as give them exposure to the maternal role. It is likely that this experience is similarly useful for a yearling rhesus monkey". Lonsdorf observes in her review that a female bias for nurturing style play has also been seen in lowland gorillas and blue monkeys.

Boy monkeys like learning from their dads, girl monkeys from their mumsThere's little doubt that biological differences between the sexes are amplified by parenting practices and parent-child relationships, including boys' tendency to want to emulate their dads and girls to emulate their mothers - as seen both in humans and our primate cousins. For instance,

in a study of capuchin monkeys, Susan Perry looked to see whether infants adopted one of two different techniques (pounding or scrubbing) for extracting seeds from fruit - girls, but not boys, typically adopted whichever technique was used by their mothers. In wild tufted capuchins, meanwhile,

male juveniles typically stick with their dads and copy their dietary preferences, such as favouring eating animals over fruit (the latter preferred by females). It's

a similar story for chimps and termite fishing with research showing how females are better at this task than males and that female infants spend more time than their boy peers watching and learning from their mothers.

"Taken as a whole," Lonsdorf concludes, "these consistent and accumulating reports of sex differences in primate behavioral development suggest that, although gender socialization in humans plays a role in magnifying the differences between young males and females,

these behavioral sex differences are rooted in our biological and evolutionary heritage."

Comment: Despite the chorus of transgender activists and their allies who dismiss science, there is growing evidence that there are inherent differences in how men's and women's brains are wired and how they work:

The cognitive differences between males and females