METI aims to send messages to the potentially Earth-like exoplanet Proxima b, as imagined by an artist. Here it is orbiting the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our solar system.

We should broadcast our own signal to E.T., rather than just waiting for it to call us, as prevailing projects have done. That's the vision of a new San Francisco-based organization called METI, or Messaging Extra Terrestrial Intelligence.

By the end of 2018, the project aims to send some conversation-starters via radio or laser signals — the mathematical equivalent of "we're here and would love to chat!" — to a rocky planet circling our nearest star Proxima Centauri, then out to more distant neighborhoods, hundreds or thousands of light years away.

It would be the first effort to send powerful, repeated and intentional messages into space, targeting the same stars over months or even years.

This could be the beginning of a beautiful friendship, said Douglas Vakoch, president of METI and former director of Interstellar Message Composition at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute in Mountain View, known as SETI.

"If we want to start an exchange over the course of many generations, we want to learn and share information," he said.

It's no small feat to send a pulse that outshines the sun. Founded last year, the international non-profit group will host two workshops next year, one in Paris and the other in St. Louis. It also plans to start fundraising for the $1 million annual budget needed to staff and build or borrow a powerful transmitter in a remote location. Part of the mission will be to figure out how to craft the perfect message to say "Hello."

If only they could just hire Adele. Instead, like much else in science, the project has turned controversial.

Opposing the effort, some ask: If aliens are hostile, do we really want them to know where we are? We should turn down the volume, so we don't draw attention to ourselves, insist science fiction writer David Brin and theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking.

"We have almost zero idea of whether aliens are likely to be dangerous," wrote physicist Mark Buchanan in an August issue of the journal Nature Physics.

Other experts say it's worth waiting until we're better conversationalists — and, then, only use well-established groups with international consultation.

We're mere youngsters in a 13.8 billion-year-old galaxy, and "babbling babies are not always appreciated during adult conversation," said Andrew Fraknoi, chair of the astronomy department at Foothill College in Los Altos Hills. "Listening and learning is how children become adults, and why not try that for a while?"

Still others endorse the effort. "I'd be happy to see this done," said Seth Shostak, senior astronomer with the SETI Institute. "I think there's something to be learned, nothing to be feared, and at least the possibility of discovering something truly revolutionary: We have company nearby."

"By reflecting on how we can communicate what it means to be human to someone who is not human, we view ourselves differently," said METI treasurer Dalia Rawson, a former dancer with Ballet San Jose and now managing director of the Silicon Valley Ballet. "By looking at our bodies, our movements, and our dance through the eyes of an alien, we gain a renewed appreciation of what it means to be uniquely human."

There have been plenty of other efforts to connect with aliens, but they've come in fits and starts. So far, no one's responded. There are no regulations for sending signals into space; anyone with a powerful enough transmitter can shout to the cosmos.

In the early 1970s, NASA's Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft carried a message in the form of a gold plaque, then a phonograph record (stylus included). SETI's Frank Drake beamed a radio message that could be assembled into a pictogram of images. More recently, we've sent arithmetic, concerts of Vivaldi and Gershwin, and the Beatles song "Across the Universe."

SETI and UC Berkeley's $100 million Breakthrough Listen project, funded by internet entrepreneur Yuri Milner, scans the heavens in hope of discovering some signature of alien technology.

The problem with only listening, however, is we're expecting aliens to take the initiative. Maybe they're politely reserved, like Canadians. Or perhaps they're just sitting around waiting for someone else to speak up first.

"If everyone who can send a message decides only to receive messages, it will be a very quiet galaxy," noted Fraknoi. And studying message transmission will aid our SETI effort, said Shostak.

What are the chances that someone in the cosmos might hear us? Until recently, it seemed a far-fetched dream. But now the Kepler space telescope has detected 2,950 confirmed "exoplanets. " While most are inhospitable places, a precious few orbit in prime real estate, not too close or far from their star.

We'd need to ping a very large number of star systems to find them. But if their residents are feeling chatty, that conversation would be one of the most exhilarating events in human history.

To be sure, we've been publicizing our musings for years, through radio, TV and military radar. So smart aliens already know we're here. And these signals aren't particularly welcoming.

"All those 'I Love Lucy' shows just say: 'We like sitcoms in our world,' " said Vakoch. "They're not saying 'We want to make contact.' "

But there are several big challenges to the METI plan.

These planets are very, very far away. In nearby Proxima Centauri, the rocky planet Promixa b is 4.25 light years away — so any reply would take more than eight years to reach us. And it's likelier that any intelligent civilization is hundreds or thousands of light years away.

So the wait time for a response could be longer than a human lifetime - or the lifetime of a NASA grant. Vakock calls it "an inherently multi-generational project."

Another challenge: Perhaps our E.T. friends will be momentarily distracted and miss our call. So we need to keep repeating a message, over time — a pattern, so it doesn't get lost in the random noise of the galaxy. And the pattern should not replicate anything else in nature, so they know it's us.

Finally, our message can't get lost in translation. We need a common "language," like math and science, to converse. Scientists think that's probably no big deal.

"If they have radio transmitters, they're good engineers. And if you're a good engineer, you've got to know that 2 + 2 = 4," said Vakoch. "That's true on Earth and it's true on Proxima Centauri."

So what do we want to say? Like a cocktail party, first impressions matter.

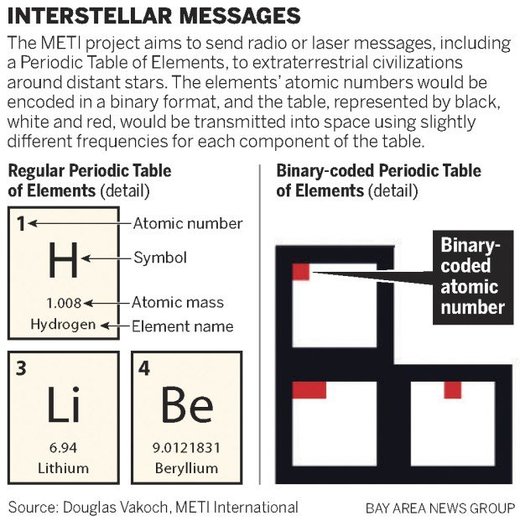

To show off our love of math, pulsing out a simple number sequence — say, 1 through 10 — seems a good place to start. We could also tell them what we're made of, by pulsing the atomic numbers of elements in the Periodic Table. We could message the Fibonacci sequence, revealing our world to be a place of elegantly patterned aesthetics.

We might even be able to share our notion of logic and cooperation by communicating game theory, where math can model coalitions and commitments.

Ultimately, there's hope for a rousing celestial dialogue, spanning millennia. Will we be here long enough to hold up our end of the conversation? That's an earthly problem.

"For our science to succeed," said Vakoch, "human civilizations need to stick around."

Soon you'll get you answer.