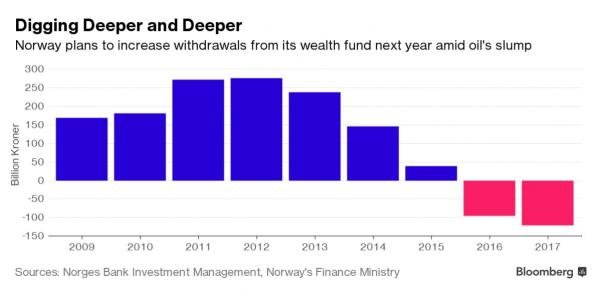

Of course, Norway's ultimate GDP potential, and therefore budget deficits, are heavily dependent on oil prices so any further weakening of crude could result in even more withdrawals. Moreover, given the substantial YoY increase, it's important to recall that there are fiscal limits imposed on fund withdrawals equal to 4% of assets, or roughly $36 billion, which could come into play at some point in the future if oil prices remain "lower for longer."

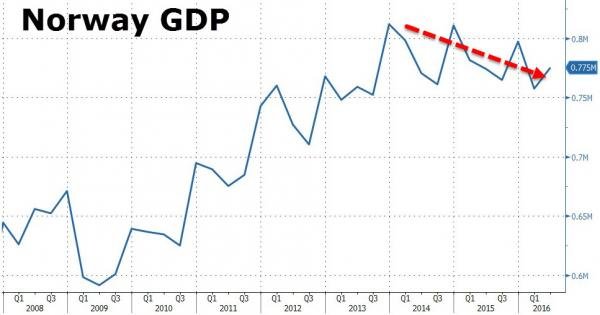

"What's worrying is the enormous pace," said Torstein Tvedt Solberg, a member of parliament and a finance committee member for Labor. The largest opposition party has asked the fund "about the threshold for when it becomes really problematic for them and the signal they've given us is that it's 150-200 billion kroner. With the pace we're seeing now, we're beginning dangerously fast to come close to the critical level."Of course the withdrawals have accelerated just as the heavily oil-dependent economy of Norway has started to absorb the impact of lower oil prices.

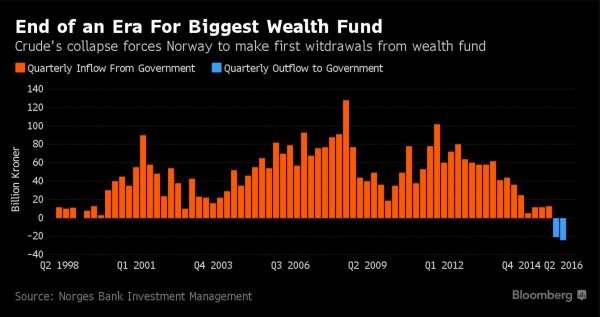

As we previously pointed out, the Norwegian government first started to withdraw funds from its sovereign wealth fund to cover government deficits in 1Q 2016.

The contemplated $15BN withdrawal in 2017, would imply a 36% surge in withdrawals over the 1H 2016 run-rate of approximately $11BN. To put those withdrawals into perspective, Norway's economy generates roughly $375 billion of annual GDP and federal spending accounts for roughly 60% or $225BN. Therefore, a $15BN withdrawal in 2017 represents roughly 7% of total government spending.

In a previous interview with Bloomberg, Egil Matsen, the Deputy Governor at Norway's Central Bank, said the withdrawals were starting to impact the manner in which the fund manages its risk profile.

"Relevant for how we think about the risk-bearing capacity of the fund. Say you have a decline in the equity market, and these returns have been partly funding the government, do you want variations in international financial markets to have a direct impact on fiscal policy?"Matsen, among others, has also questioned whether the 4% fiscal limits on withdrawals were the right cap in the current return environment noting that "as the older bonds come to maturity and are reinvested, a big chunk of that will be reinvested in bonds with very low or even negative yields."

But Finance Minister Siv Jensen dismissed criticism of the withdrawals saying that the administration is using the fund as was intended noting that withdrawals remain below the fund's annual return target of 4%.

"Now that we are in an extraordinary situation, hit by the biggest oil price shock in 30 years, it would be crazy if we didn't have an expansionary fiscal policy," she told Bloomberg. Jensen rejected suggestions that the fund was "vulnerable." She described it as "rock solid."While we could debate the merits of Norwegian fiscal policy, at least the country is actually funding deficits as they're incurred. That would seem to be a "slightly" better approach than the U.S. plan which calls for printing more cash to fund massive deficits while ignoring the long-term impacts of ballooning national debt that can't possibly ever be repaid.

The fund's managers have warned it's getting harder to live up to a real return target of 4 percent. It has returned 3.44 percent over the past 10 years. For now, planned withdrawals aren't big enough to force the fund to sell assets. It estimates income from dividends, real estate and bonds will reach 207.5 billion kroner next year, almost double the amount the government plans to withdraw.

Comment: Norway currently has the third largest soverign wealth fund: