Were the 13 Colonies really that important?

I see some answers which portray the mainland colonies as not much of a loss for Britain and which cite the Caribbean sugar colonies as more important. Some ministers at the time did in fact point out that the northern colonies of New England contributed little economically and were expensive to defend. The Southern colonies were seen as more commercially advantageous due to rice and tobacco exports (this was the thinking behind the Southern Strategy in the war. While the Caribbean was a vital part of the Atlantic economy (worth about £50- 60 million in 1775) the economy of the mainland colonies was growing rapidly. In 1700 the colonies were one of the least significant parts of the British Empire but by the time of the revolution they had exceeded the Caribbean in terms of total British trade (imports and exports combined with re-exports). By 1776 the 13 colonies accounted for 17% of total British trade, while the Caribbean accounted for 15%. The American colonies were also the most important market for British products during the 18th century accounting for 37% of British domestic exports.

The colonies then, were important economically - however the majority in the British leadership saw them as important for reasons that had more to do with European Imperatives; namely the balance of power. Backing down in the row with the colonies would involve considerable loss of face and would provoke - as one ambassador put it - 'the scorn of Europe'. Others believed that American resources were vital for the struggle against the Bourbons - for example as an essential pool of seamen for the navy. Shipbuilding was also an important concern; in 1774 30% of Britain's merchant fleet was American made. In general the opinion in British ruling circles was that America was vital to maintain Britain's European position; not for financial reasons but for strategic and moral reasons.

We now obviously view the situation through the lens of the separate histories of the United States and Britain; viewing them in turn as separate entities. At the end of the revolution however it seemed as if Britain itself had been partitioned. In 1770 the population of the 13 colonies was perhaps 2,148,000. Although this may seem small it needs to be seen against a total population in Britain and Ireland of perhaps 11,971,000 with another 436,000 in the West Indies. In relinquishing her colonies therefore, Britain was losing some 14-15% of her population and a territory the size of a continent. Worse still the population of the American Colonies was growing at a rapid rate and was closer to 3 million (including slaves) by the time independence had been achieved (it had only been a mere 251,000 in 1700). None of this was lost on contemporaries.

Britain's Vietnam?

I see it also argued that the conflict was the equivalent of Britain's Vietnam. This has been argued in some works on the period - for example, A few Bloody Noses by Robert Harvey. In some sense this is a decent comparison - the conflict posed important questions about Britain's strength as a world power - but it risks misrepresenting the conflict. Unlike Vietnam or Iraq the 13 colonies were part of the British Empire and settled mainly by British colonists who prided themselves on being extensions of British society overseas (leaving aside substantial populations of Germans and a large African slave population). The war was a rebellion and a civil war within the British Atlantic World.

There is a tendency to view the American Revolution as an inevitable success. This view tends to emphasize the sheer futility of subduing an entire continent in rebellion; especially when the rebels had no specific nerve center and benefited from space, resources, a diffuse leadership and military and political autonomy. For example, if Washington's army had been cut off in New York in 1776, the British would still have had to occupy America with a force numbering 40,000 troops - a seemingly impossible task.

In fact the British had a decent strategy and set of war aims that might have been successful in the event of a decisive victory. The aim for the British - principally Lord North and the Howe brothers was for the restoration of government under consent under the crown. The way was thereby open for a compromise victory whereby the rebel leaders - men of means with a lot to lose - could have been placated and brought back under control. A precedent for this was the resolution to the Rákóczi Uprising (1703 - 11) which had been successfully supressed by the Habsburgs. What was needed was a decisive military victory that would bring the Americans to the negotiating table. In addition to this the British would need to keep the rebels from obtaining a European ally which would provide them with the backing needed to resist; or if the Americans did succeed in obtaining an ally (most likely France) to tie this ally down through European alliances and coalitions.

The failure to achieve either of these objectives was the reason that Britain ultimately lost the war.

The failure to achieve a decisive victory in America

The British military lost because - despite winning most of the engagements it took part in - it never really got its army to where it needed to be in order to land a decisive blow. At the eruption of the conflict the British army numbered a mere 27,000 men. By six years into the war a large scale mobilisation occurred - including the recruitment of German mercenaries from allied states - and British manpower increased to 150,000 troops. This was an impressive force but most of these were never deployed to North America. At the time of Yorktown only around 35,000 regulars were stationed in the mainland colonies and these were spread thin over a large area. The Americans were also short of troops but the British did not have enough of a relative advantage to be able to capitalise. Two options would have been to arm more Loyalists or do more with emancipated slaves but neither of these were pursued with enough vigour.

When British armies did capture cities - such as at Philadelphia and New York - they were inevitably tied down with garrison duty and unable to mount offensive operations. Logistics made the problems worse with the army reliant on provisions from overseas. Many supply ships fell to storms, privateers or enemy action so that British armies were effectively tethered to coasts and rivers.

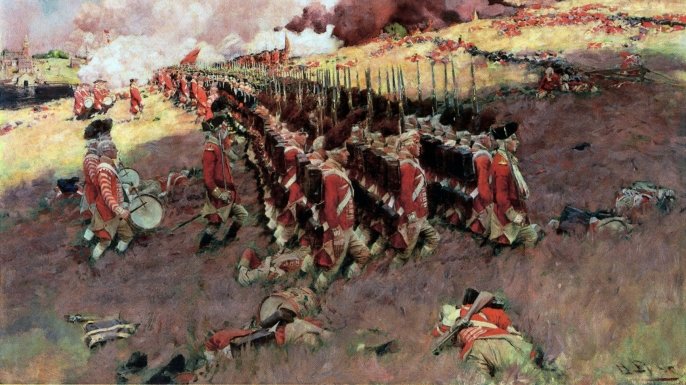

I recall a conversation some years ago between myself and my wife (who hails from Boston). When explaining the American victory in the War of Independence to me she said that it had resulted because the colonists had hid behind trees and sniped at the British while they stupidly marched very slowly towards them in bright red outfits (they might just as well have painted targets on themselves). Actually - as I should have said at the time - the Americans were pretty faithful to the European style of warfare and fought in much the same way (nor were the British shy about deploying irregular forces). At Bunker Hill, New York, Saratoga, Brandywine, Charleston, Guilford Court House and Camden the Americans chose to fight fixed European engagements and contrived to lose most of them. George Washington for example was recently voted the most formidable military opponent ever faced by Britain. In a certain sense (keeping his army intact and resilient) this is true but his performance at times was so bad at times he was nearly sacked in favour of General Gates. He succeeded in maintaining a siege of Boston and forcing a British retreat but he also ordered the disastrous invasion of Canada and presided over the near collapse of his army at New York in 1776. He was successful at conducting raids at Princeton and Trenton but he also lost at Brandywine and Germantown later that year. In the entire war after the Princeton and Trenton raids he had only one success - the shining exception of Yorktown.

If this was the case then why were the British unable to make the most of their victories? The answer lies in the fact that the rebels were able to avoid major confrontations under disadvantageous circumstances. The single opportunity the British had to destroy the bulk of Washington's army was in 1776. After this the Continental army's strategy was not to engage the British army where it would not have the opportunity to retreat. During their defeats the rebel commanders were pragmatic and were able to withdraw in good order. British commanders found it difficult to pursue retreating forces, often because of a lack of provisions and a lack of manpower reserves for attending to the wounded while remaining on the offensive. The ubiquitous woods and high fences of the American landscape provided a further barrier and the challenges of operating in America led to physical and mental exhaustion among the British army.

The best resource for turning an American tactical retreat into a rout was cavalry. While these were deployed successfully at the battle of Camden (Tarleton's dragoons) they were very short in numbers. Only two cavalry corps were despatched to America and these were spread very thin. Inevitably many were lost on the sea voyage over and there were severe difficulties obtaining replacements. In any event cavalry were effective really against large broken masses of troops. American commanders were successful in both leaving the field in good order and using rebel horse to give cover.

As a result British force won most of the engagements in the war but their victories only succeeded in cutting deeply into their limited manpower supply; they failed to neutralize the rebel field armies and failed to convince colonial public opinion the British army was invincible.

There were probably only two chances for Britain to win the conflict. Howe probably had the best chance in 1776. Instead due to excessive caution; he failed to trap the rebels on Long Island. He then permitted them to escape from Manhattan and retreat across New Jersey. By the end of 1776 Washington's army was disintegrating due to its voluntaristic character; men simply laid down their arms and headed home (the Trenton raid was in part an effort at a recruitment drive to persuade veterans to re-enlist). Howe's chance went when he failed to act in conjunction with Burgoyne's invasion from Canada. After this the British switched to a maritime strategy centering on the control of ports and coastal areas.

The second chance to win the conflict was in 1780 with the Southern Strategy. The Americans by this stage were facing exhaustion and war weariness; their army was living hand to mouth and at risk of mutiny. Hyperinflation had left the economy of the colonies in ruins and reduced household wealth by 45%. A decisive battlefield victory at this point would probably not have won back the Northern colonies but might have resulted in the British retaining the South which was more valuable economically. Instead the British in the South were drawn into a struggle with partisans and Cornwallis made the disastrous decision to march north into Virginia. Here he was defeated - mainly due to a massive failure of British Foreign Policy and a global war in which the odds were increasingly stacked against the Crown's forces.

A failed Foreign Policy - How Britain lost America in Europe

In the early to mid-eighteenth century Britain won three wars in succession; the Spanish Succession, the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War. In each case the wars were won because Britain led an international coalition against France and successfully cultivated European Alliances. By the end of the War of Independence the conflict had ceased to be between Britain and the rebellious colonists, instead the war was now a worldwide conflagration between Britain and France, Spain and Holland. Britain was also in a state of cold war with Russia, Austria, Prussia and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Denmark and Sweden. The entry of the three most significant European naval powers into the war between 1778 and 1780 turned the balance on the high seas temporarily but fatally against Britain. Clearly British's diplomacy had failed miserably.

Britain after the Seven Years War was more focused on its imperial and naval destiny at the expense of its strategic position in the Europe State System; so much so that by the time of the revolution it had been isolated in Europe for 10 years. This attitude was perhaps encapsulated by the figure of George III who rarely went to Hanover and seemed to many to embrace Britain over continental commitments. British involvement with Europe courts diminished and this retreat to the sidelines left Britain deprived of influence. This was a favorable situation for the rebels who - like the English revolutionaries of 1642 and 1688 - sought a foreign intervention to defend their cause.

Comment: [link]

The rich and landed American leadership, . . . found ready-made supporters in the European Bourbon royal family (Catholic rulers of France and Spain).

The most likely candidate for a European ally on the American side was France. The Comte de Vergennes - the French foreign minister - wanted to diminish Britain as a world power but was uneasy about the Americans as allies (the rebellious subjects of a lawful monarch and a potential future threat). He also needed time to be able to complete the Bourbon naval building programme. Lord Germain's tactic to counter this threat was to seek decisive victory in America and isolate the continent from Europe. As we have seen both of these ultimately failed - the American armies remained intact and the navy was unable to protect trade or prevent the supply of European munitions to America. In 1778 France entered the war.

The trigger for French intervention was partly the British defeat at Saratoga (where most guns on the American side were supplied by the French) - but the main factor was British attempts to negotiate with and conciliate the rebels. This was too little too late but the measures were enough to provoke the French into action for fear of an Anglo-American rapprochement. With France's entry Britain now faced a mortal threat in Europe. In Ireland rebellion by Irish Jacobites became a constant threat. King George III's German territories were now exposed to an attack by the French and the Austrians and the French could now put pressure on the other German principalities to withdraw their mercenaries. As a result Britain was forced into mass-mobilisation and to spread its forces more thinly.

The priority now was to keep Spain from joining France and by doing so prevent a union between the two Bourbon fleets. The prospect for doing so seemed good in 1778 given France and Spain's divergence of interests and the distain the Spanish government felt towards the American colonists (not wanting to create a precedent for rebellion). Another priority was to find another alliance in Europe that could contain the French. The best prospect for this was the rupture between the Austrians and the Prussians over the Bavarian succession - this might have had the effect of drawing in the French on the side of the Elector Palatine. In the event this did not happen; no European power was prepared to ally with Britain. Furthermore Vergennes was determined not to be dragged into a European war and intended to concentrate on the colonial struggle (he was heedful of the critiques of Louis XVI's foreign policy).

Britain therefore had little hope of a continental diversion which would tie up the French; all the more important to keep the Spanish on-side. Despite offering the Spanish West Florida as a sweetener the Spanish were intent on recovering Gibraltar and Minorca so the offer was rejected. Spain entered the war in 1779, thereby shifting the naval balance against Britain and making her position in the Mediterranean precarious. By 1780 the Franco-Spanish fleet exceeded that of Britain by 44% and the French were able to begin picking off British sugar isles (including Grenada, the second most important). By 1779 while the British were engaged in their Southern Strategy in the colonies the British Isles were also threatened by a Franco-Spanish invasion fleet and Ireland was in ferment. 30,000 troops were assembled in northern French ports and an armada stood poised.

Luckily for the British the invasion was called off due to the weather and Bourbon timidity. At the same time associations appeared in England to agitate for parliamentary reform; these brought forth mobs and domestic unrest - much of it driven by international failure and the low standing of the ministry and Crown.

After the Spanish declared war the main hope was to secure Russia and Austria and thereby create an alliance which would force France to break off the war in America. Russia proved anti-British and more interested in whacking the Ottoman Empire. Negotiations with Austria showed promise but ultimately went nowhere. In 1780 Russia, Austria, Prussia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Holland, Denmark and Sweden signed an armed neutrality agreement which was intended to protect neutral shipping against the British. This served to highlight Britain's complete isolation and it was followed by the entry of the Dutch into the war.

Beginning in 1778 with the entry of France, the widening of the war began to have serious effects on the conflict in America and rendered the theatre a strategic backwater. The focus of the War of American Independence shifted to the West Indies and India, and the main event became the struggle between Britain and France; primarily a naval fight for the security of home waters. The British army had to be scattered more widely as it now had to guard scattered possessions in the Caribbean, India, Africa and the Mediterranean. The Royal navy lost its superiority to the Spanish and the French, thereby leading to the battle of the Chesapeake and the encirclement of Cornwallis's army at Yorktown. Secret French aid sustained the rebels and provided them with supplies and arms. While the Royal navy was able to support and reinforce the army in the pre-Bourbon stage of the war it was no longer able to do so subsequently. Tied down by global commitments, the flow of troops to America ceased. After Yorktown offensive operations in the American theatre virtually ground to a halt and the colonies were effectively conceded.

Conclusion

At the end of the war the British had not been entirely unsuccessful. They had been able to sustain their position in India, hold on to Canada, Jamaica, Gibraltar and Madras, clobber the Dutch and defeat the French fleet in 1782. They had however relinquished the 13 colonies, Florida, Tobago, Senegal and Minorca. The first of these was the biggest loss and was held - incorrectly - by contemporaries to herald the decline of Britain as a world power. Instead trade between Britain and America expanded rapidly and Britain built a second empire in the East. France slid into terminal decline, suffered a collapse in state credit and lost its European allies thereby opening the door for its own revolution in 1789.

For more information, see the rest here [link].

Was concocted in England, not a consequence of French decline.