© Karl Tate / Live Science

In the shop window gleams the coolest pair of shoes ever. Despite being able to afford them, some people will walk away, while others - though the purchase blows a hole in their personal finances - grab the kicks anyway.

We all have to spend money for necessities, such as groceries or rent. Occasionally, we also

indulge on unhealthy treats and entertainment. Two contrary sorts of people, however, struggle to open their wallets even for things they really need - "tightwads" - while others can't stop their shopping sprees - "spendthrifts."

"Tightwads spend less than they should," said George Loewenstein, a professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University. "They recognize that they should be spending more for their own wellbeing. The spendthrifts are the opposite. They spend more than they should spend by their own self-definition."

Studies have revealed a possible basis in the brain for why money burns a hole in some peoples' pockets while the mere thought of spending makes others grimace. Understanding why people under- and over-spend can help with ensuring they don't unduly burden themselves - or their bank accounts - when making a purchase.

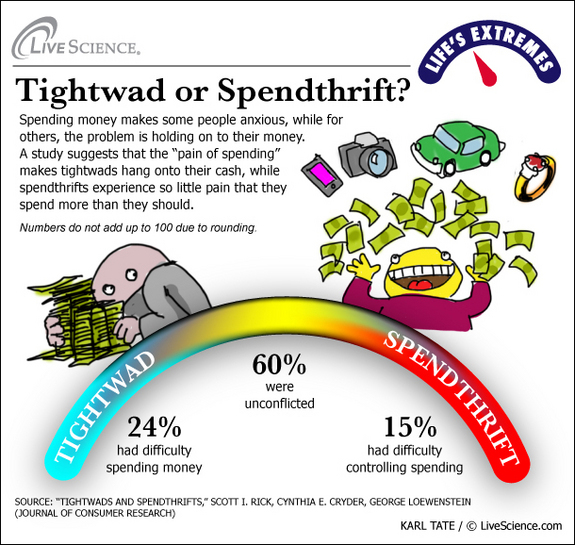

To save or spend, by the numbersTo gauge how many people qualify as spendthrifts or tightwads, Loewenstein and his colleagues surveyed more than 13,000 people, beginning back in 2004. Respondents reported how their scrimping and splurging diverged from their desired spending habits.

The researchers reported in a 2008 study that 3,248 respondents proved to be tightwads and 2,046 were spendthrifts. Percentage-wise, that works out to about 25 and 16 percent of the general population, respectively.

The results also showed that males were three times more likely to be tightwads than females, who showed no bias toward either category. Spendthrifts, as might be expected, who used credit cars were three times likelier to have debt than tightwads who also swiped the plastic. Income levels, did not vary much between the two camps, suggesting that spending decisions arose not from the size of one's cash pile but from ingrained spending behaviors.

Money on the brainTo get a sense of what happens in our brains when we consider dipping into the bank account, Loewenstein and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. This brain scanning technique monitors blood flow to areas in the brain activated when performing a task.

When study subjects looked at a desirable item, such as chocolate candies, their brains produced a starkly different response than when viewing the item's price tag.

"We would first show [the study subject] the product, and if they liked the product, the reward centers of the brain would light up," said Loewenstein. "Then we'd show them the price and the pain and disgust regions activated."

The key reward center the researchers saw light up was the nucleus accumbens, which plays a key role in pleasurable acts from having sex to hearing music. The specific pain-and-disgust region involved was the insula, which activates upon smelling foul odors or experiencing social exclusion, among other situations.

The findings suggest that that the emotional pain or anxiety of actually having to pay for an item works to keep our pleasure seeking in check.

In some people, the researchers think, this mental anguish is so strong that it overrides rational deliberation; these people are tightwads, and they don't buy something even when they know they should.

For a spendthrift, the pain of throwing money around does not register in the brain like it does for other people.

Paper or plastic?Cash versus credit card spending habits have opened a further window into the psychological workings of

tightwads and spendthrifts, said Scott Rick, a professor of marketing at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business and a co-author on research papers with Loewenstein.

Tightwads find it very difficult to part with cash, incurring a big spending gap with their less tight-fisted counterparts, especially on unnecessary "vice" products. But when using credit cards, this gap disappears.

"Several papers propose, as well as ours, that it is

less painful using credit cards," Rick told LiveScience. "Not giving up anything tangible kind of helped cure the tightwads of their affliction." For spendthrifts, the medium of purchasing power didn't really matter, Rick added, "because cash feels like credit to them."

In related findings, Loewenstein and Rick have proposed that being frugal is not the same as being a tightwad. Frugal people receive pleasure from watching the money pile up, with a penny saved being a penny earned. "A tightwad finds it painful to spend," said Loewenstein, "and a frugal person finds it enjoyable to save."

It's all about the BenjaminsThe researchers have some advice for tightwads looking to loosen up. Tightwads can experiment with multiple bank accounts, for example, dedicating one to savings and another to spending, said Loewenstein.

Spendthrifts, meanwhile, can lessen the damage to their bankroll by avoiding credit cards and setting weekly budgets. Any number of books and online tips are out there to help those who

compulsively spend on the cheese. "There's much more advice available to spenders than tightwads," Loewenstein noted.

As for businesses seeking to cash in on spendthrifts and even getting tightwads to make it rain, to a large extent they already have people figured out, Loewenstein said. Ubiquitous credit card machines have replaced the forking over of bills, for instance, as well as music and screaming sales signs. Casinos for their part wisely go with chips rather than actual units of hard currency, not to mention the flowing alcohol.

"I think the retailers already are way ahead of the game on these matters," Loewenstein told LiveScience. "They have an exquisite understanding of the pain of paying."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter