The setup allows for real-time, almost-real-motion tracking of single neurons. That feat has eluded researchers who have a fuzzy, general understanding of brain systems, but little knowledge of how individual cells actually work. They hope that cell-level details will make sense of motion, cognition and other complex mental functions.

"One of the major research areas of neuroscience is the development of techniques to study the brain at cellular resolution," said Princeton University neuroscientist David Tank, co-author of the study published Wednesday in Nature. "The information of the nervous system is contained in the activity of individual neurons."

Tank's team studied hippocampal place neurons, which are activated when an animal is in a particular location in its environment. Ever since hippocampal place neurons were identified 40 years go, scientists have wondered exactly what mechanisms make them fire.

However, the fMRI machines used to study brain activity in humans only measure the average output of millions of neurons at once. Studying individual neurons has been possible in cell cultures, but brains in a dish behave different than real, living brains. Tracking individual neurons in moving animals has been impossible.

"The neurons move back and forth while you're trying to measure things," said Tank. "So we developed a way to keep the head fixed in space, but still have mice perform behaviors that are usually studied in mice running through a maze."

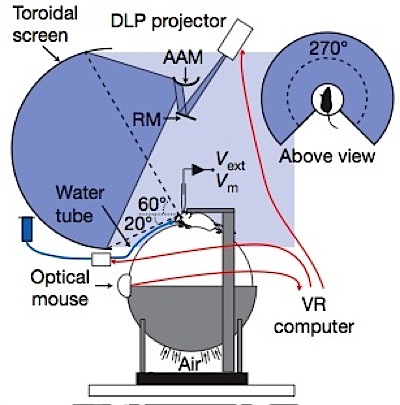

Tank's team designed an apparatus in which a mouse, its head firmly held in a metal helmet, walks on the surface of a styrofoam ball. The ball is kept aloft by a jet of air, so that it functions like a multidirectional treadmill. Around it are sensors taken from optical computer mice, which read the ball's movement as the mouse runs.

Those readings were the input for the researchers' virtual reality software - a modified version of the open source Quake 2 video game engine, tweaked to project an image on a screen surrounding the mouse. Tank called it "a mini-IMAX theater."

Mice in the study ran through a virtual maze designed in the open source Quake game editor, but rather than earning points or power-ups, they were rewarded with sips of water from a head-side nozzle.

Into the hippocampus of each mouse the researchers inserted a glass capillary just one micron wide at its tip and filled with salt water. Known as a whole-cell patch recorder, it detects electrical currents as they pulse through individual cells.

"It is difficult to overstate the importance of understanding how the dynamics of electrical activity within single neurons is related to firing patterns among collections of neurons that accompany the performance of complex tasks," wrote Douglas Nitz, a University of California at San Diego cognitive scientist, in a commentary accompanying the findings.

Scientists have proposed at least a half-dozen models of individual neuron behavior to explain the general firing patterns of hippocampal place neurons, whose general behavior is determined by a creature's specific spatial location. Tank's team found that individual neurons fired in staccato bursts of varying intensity, a result that fits one of the proposed models.

Those results are likely of interest only to neuroscientists, and "to be fair, more work is needed to nail this down," said Tank.

Nitz was less reserved, calling the observations "an exciting result" that "may prove generalizable to other brain structures, in particular the cerebral cortex." But he too was especially excited by the virtual reality-harnessing methodology.

The findings are "a first payment on the promise of the technique," and "represent a powerful example of what will be learned in decades to come," wrote Nitz.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter