Such observations could help conserve dwindling fish stocks, says Nicholas Makris, an oceanographer at MIT, who led the study.

"If we see what's in the ocean we'll be more mindful of conserving it," he says.

The technology - called ocean acoustic waveguide remote sensing (OAWRS) - has also helped researchers confirm theoretical predictions as to why and how so many animals get together and act as one.

"I don't know anything that's close to this scale," says Iain Couzin, a biologist at Princeton University in New Jersey, who was not involved in the study.

Echoes of herring

OAWRS is different from sonar-based technologies in that it sends out lower wavelength sound waves that travel further through the ocean.

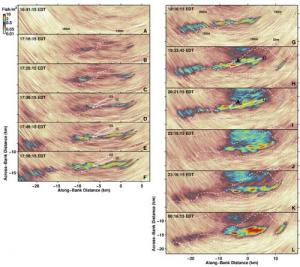

Traditional high-frequency beams dissipate within about 100 metres. Yet with one vessel sending and another receiving the waves, researchers using OAWRS can take a snapshot of a 100-square-kilometre area every 75 seconds.

This kind of resolution was perfect to record the formation and growth of Atlantic herring shoals, Makris says. The fish congregate en masse to find mates more easily and to protect against predators.

Makris and Purnima Ratilal, an oceanographer at Northeastern University in Boston, spent about a week in 2006 measuring shoals in Georges Bank, about 100 kilometres off the coast of Massachusetts.

Fish mob

Much of the time, fish stick to themselves in deeper, darker waters. As the sun begins to set, "some brave group will cluster, rise a little off the bottom and start to horizontally converge," Makris says. "Once that initial cluster forms, the fish next to the cluster start to converge, and you have a wave propagating."

The shoal saunters toward shallower waters, where the herring breed. Makris' team didn't capture the dissolution of these shoals, but a previous study suggested that dawn marks the end of the party.

"We're at just the tip of the iceberg in understanding how the physics of these systems work," Couzin says.

Scientists have never before gathered data on so many animals acting in concert. Understanding these herring shoals should spawn more general theories about what causes animals to coalesce, he says.

Save the fish

The ability to measure huge numbers of fish at once should also help guide conservation efforts.

"If we had this OAWRS system and we were looking [at Georges Bank] 500 years ago, all we would have seen is cod," Makris says. "Now you look out there and there's no cod to be seen."

Makris would like to take the technology to Alaska, to help prevent a similar collapse in that state's pollock fishery.

Ron O'Dor, a marine biologist at the Census of Marine Life in Washington DC, says that putting hard numbers on fish populations will give policy-makers and stake-holders more incentive to take action.

"Some people think I'm naïve. If you can clearly show fishers what's happening to a stock and it's their livelihood, they're going to respect them," he says.

Journal reference: Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.1169441, in press)

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter