It appears that the workers, or should we say workmen and artisans, the people who built the rock-cut tombs of the Pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings from about 1500 BC onwards, may have later been employed on a project aimed at "emptying" and "recycling" their contents -- or that, at least, is what Rob Demaree of Leiden University thinks.

In his recent talk at the Dutch Institute in Cairo, Demaree said that an impressive number of texts on papyri, ostraca and graffiti had provided researchers with extensive information on the workers' community at Deir Al-Medina, especially from the Ramasside Period and the second half of the New Kingdom, but that in spite of all our knowledge we did not know what happened at the end of this period when the Ramasside line of kings was no longer in power and no more royal tombs were built. "Now, thanks to a largely unpublished dossier of texts, we are gradually beginning to understand what happened to them," he said.

Demaree, who studied Egyptology in Leiden, Copenhagen and Oxford, and who obtained his PhD on "Ancestor Worship in Ancient Egypt", was aware that not all members of the audience were au fait with the earlier phases of the workmen's village on the Theban necropolis, let alone the final phase, so he started his presentation by outlining what had taken place earlier. To recap, he said that the settlement was founded some time in the early 18th Dynasty, in the reign of Tuthmosis I (1550--1525 BC), the first Pharaoh definitely to be buried in the Valley of the Kings, and that in its earliest stage there was no resident community -- just a village of some 40 houses to accommodate itinerant workmen hired for short periods of time. Later the settlement was expanded to accommodate a special group of artisans -- "expert artists" might be a better word -- and, from literary evidence recovered from the village, it appears that more than 100 people, including children, lived in the village, off and on, for several centuries.

"The situation changed after the Amarna period, in the 19th and 20th dynasties (1307--1070 BC) when the workers who plied their trade in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens lived, worked and died at Deir Al-Medina, and built large and finely-decorated tombs for themselves," Demaree said. He went on to explain that texts had survived which told us about their lives and the organisation of their work.

During their weekly labour, the workers stayed in a small camp built on a ridge above the royal valley. The work force was divided into two -- one working on the left side of the tomb, the other the right side, the numbers varying according to the size of the tomb. Each work force was under a foreman, and several scribes reported the progress of work, worker absence, and payments.

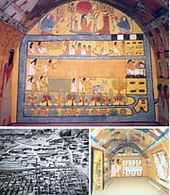

Gradually the workers formed an elite class, as is evident from the contents of their homes and their tombs at Deir Al-Medina. The extant tomb of Sennedjem, for example, which was discovered early in the 20th century, clearly reveals the high quality of life expected in the afterlife, a lifestyle similar to that on earth. He and his wife are shown dressed in white linen, ploughing and reaping in a fertile hereafter; with protective deities guarding his sarcophagus; while other wall paintings show the deceased and his wife returning from a ritual journey to Abydos. These paintings are some of the finest on the necropolis.

The workmen's village at Deir Al-Medina is situated to the north of the small and graceful late Ptolemaic temple. Ever since it was cleared by a French archaeological mission between 1922 and 1951, a succession of scholars has worked on the masses of archaeological and literary evidence recovered from a large pit containing some 40,000 pieces of pottery and scraps of papyrus. Through these, the mission has been able to trace the family histories of each of the inhabitants of the village throughout a span of nearly three centuries: as well as their daily activities, religious ceremonies, marriages, pride in their work, magic texts, and even their antagonisms and jealousies.

"At first no one had a real idea of what the community was for," Demaree said. "But gradually they came to realise that it was to prepare the royal tombs. This was really a construction department under a vizier, and Demaree credited two scholars, Bernard Bruyere and Jaroslav Cerny, for revealing a main street in a community of 500 to 600 people, and by far the largest amount of evidence of a workmen's community ever to be found. Indeed, it is somewhat ironical that today we know more about the lives of the workmen who cut the New Kingdom royal tombs than we know about many of the Pharaohs for whom they were built.

The men of the village were all skilled workers who toiled in the Valley of the Kings for 10-day stretches, and slept in makeshift shelters in a mountain pass above the village until their term of work was over. They worked under a strict system of administration, all classified according to their work. The designers and scribes ranked highest, artists, painterss and draftsmen next on the scale, then quarrymen and masons, and at the bottom of the scale were the porters, diggers and mortar mixers. In charge of the whole community was a Director of Works, and the various foremen immediately under his control.

Attendance was strictly marked. An absent worker had to account for himself. The written excuses, which have survived the centuries, reveal that one had to "visit my mother-in-law"; another had to get urgent supplies from the market; and illness was a frequent excuse. Payment came regularly each month in the form of charcoal, dried meat, fish, bandages and cloth, along with materials for their work. When the caravan failed to turn up and there was a backlog of salaries, this led to the famous Revolution of the 20th/21st dynasties written on papyrus.

With the death of Ramses X and Ramses XI, work at the royal valley came to a close. We know this because their tombs were left unfinished. The subsequent period was one of decline, during which no royal tombs were built. "So what did the workers do?" asked Demaree. "We wondered about that because texts on the final phase of occupation of the village were lacking."

Thanks, however, to a largely unpublished dossier of texts of an earlier period -- in the time of Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III (c 1473--1353 BC) -- as well as from the ostraca from various collections around the world, Demaree's painstaking research resulted in what he called "a great surprise!"

"The material revealed that, under Ramses IX, it was no longer safe in the village and the community took refuge near the Temple of Deir Al-Bahari where they created tombs for the Priests of Amun, and, under a new boss of a new dynasty in Thebes, the ruling elite appears to have been given orders to empty the royal tombs and recycle the objects," Demaree said. He provided several examples of "the re-use of royal coffins that the worker's forefathers had created for the Ramasside kings."

Pharaoh's high-ranking officials

Paser was a vizier during the reign of Seti I, and he continued to serve under Ramses II. His job was to organise and direct major projects of state and to supervise production and officiate at major religious festivals, as here shown in a scene from his tomb at Thebes. One of his main duties was to oversee the construction of his Pharaoh's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, and it was he who organised the necessary workforce, dividing the workers into two gangs -- one working on the right side of the tomb and one on the left -- each under a foreman.

The name of the foreman of the left side of Seti's tomb was Hay. He seems to have spent his whole life working in the royal valley, which is to say from about 1214 to 1174 BC. His father before him was a foreman, and young Hay worked beside him from childhood, continuing to work in the valley after his father died. He appears to have been a kind and pious individual, and obviously a dedicated one because the tomb of Seti I, discovered by Giovanni Belzoni in 1817, far surpasses all others in the Valley of the Kings both in size and in the artistic execution of the sculptured walls. Every inch of the wall space of its entire 100-metre length is covered with representations which were carried out by the finest craftsmen.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter