Humans were hunting large mammals in North America about 800 years earlier than previously thought, new analysis of a controversial mastodon specimen - with what appears to be a spear tip in its rib - seems to confirm.

The find suggests humans were hunting mastodons using tools made from bone about a thousand years before the start of the "Clovis culture", reputedly the first human culture in North America. Other evidence points to mammoth hunting using stone tools around this time, but the notion of pre-Clovis hunting has remained highly controversial.

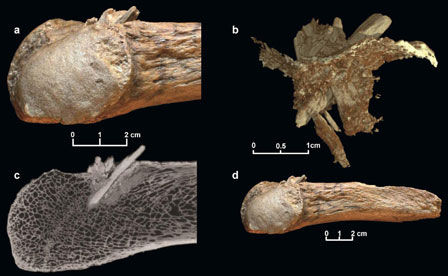

The mastodon was found in 1977 by a farmer called Emanuel Manis. He contacted archaeologist Carl Gustafson, who excavated the skeleton and noticed a pointed object embedded in its rib. Gustafson took a fuzzy x-ray and interpreted the object as a projectile point made of bone or antler.

By dating organic matter around the fossil, he estimated that it was about 14,000 years old. Other archaeologists challenged Gustafson's dates and his interpretation of the fragment as a man-made point.

Comment: The reader is encouraged to review this in-depth article which sheds more light on this subject: New Light on the Black Death: The Cosmic Connection by Laura Knight-Jadczyk.