Although modern humans, Homo sapiens, are the only human species alive today, the world has seen a number of human species come and go. Other members perhaps include the recently discovered "hobbit" Homo floresiensis.

The human lineage, Homo, evolved in Africa about 2.5 million years ago, coinciding with the first evidence of stone tools.

For the first half of the last century, conventional wisdom was that the most primitive member of our lineage was Homo erectus, the direct ancestor of our species.

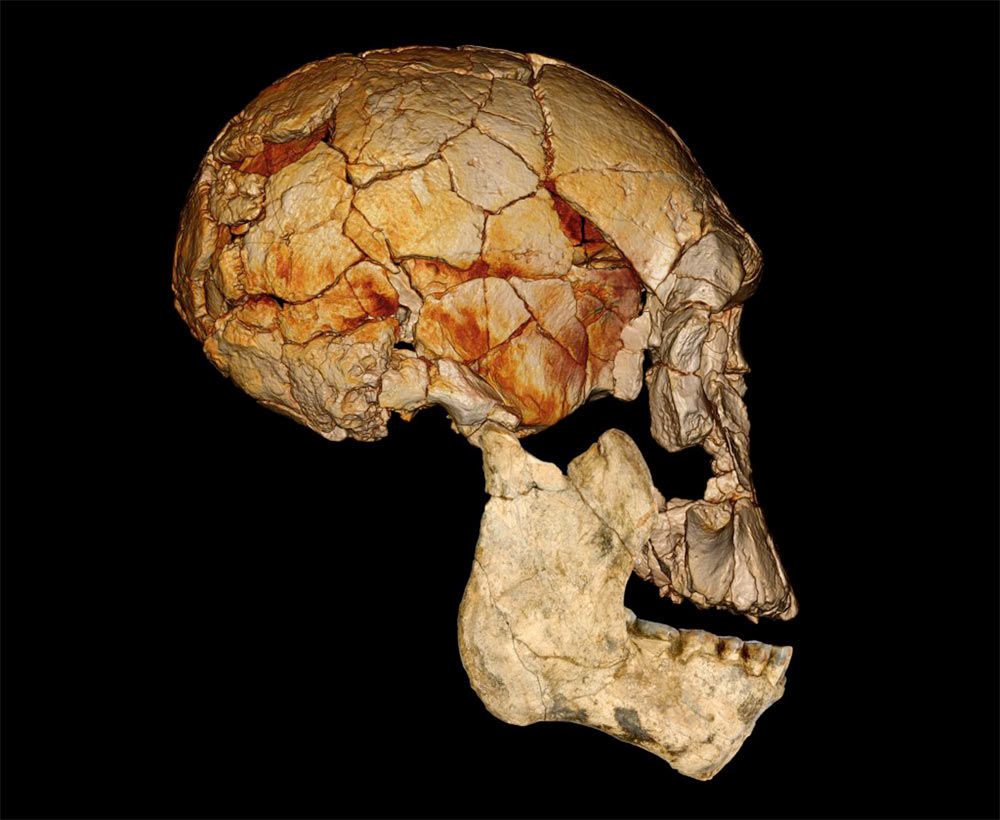

However, just over 50 years ago, scientists discovered an even more primitive species of Homo at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania they dubbed Homo habilis, which had a smaller brain and a more apelike skeleton.

Now fossils between 1.78 million and 1.95 million years old discovered in 2007 and 2009 in northern Kenya suggest that early Homo were quite a diverse bunch, with at least one other extinct human species living at the same time as H. erectus and H. habilis.

"Two species of the genus Homo, our own genus, lived alongside our direct ancestor, Homo erectus, nearly 2 million years ago," researcher Meave Leakey at the Turkana Basin Institute in Nairobi, Kenya, told LiveScience.

However, making comparisons between these fossils was difficult, because no single purported H. rudolfensis specimen contained both the face and the lower jaw, details needed to see if it was indeed separate from H. habilis. Any supposed differences between H. habilis and H. rudolfensis might, for instance, have been due to variations between the sexes of a single species.

The newly discovered face and lower-jaw fossils, uncovered within a radius of just more than 6 miles (10 kilometers) from where KNM-ER 1470 was unearthed, now suggest that KNM-ER 1470 and the novel finds are indeed members of a distinct species of early Homo that stands out from others with its uniquely built face.

The environment was more verdant back then than it is today, with a larger lake. "There was plenty of opportunities ecologically to accommodate more than one hominid species," Spoor said.

Other researchers suggest these new fossils are not enough evidence of a new human species. However, "these are really distinctive shape profiles - it really shows something completely different," Leakey said. "I feel pretty confident that we're not just dealing with variation in one species."

In principle, researchers might be able to reconstruct what this new species might have eaten by looking at its teeth and jaws. "The incisors are really rather small compared to what you'd find in other early Homo," Spoor said. "In the back of the mouth, the teeth are large, telling us a lot of food processing was going on there ... it may be possible it ate more tough, plantlike foods than meat."

Other extinct human fossils discovered in that area are thought to belong to H. habilis. As such, at least two different species once lived in that site in northern Kenya. However, it remains possible these other fossils do not belong to H. habilis, suggesting yet another species lived there at the same time, paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood at George Washington University at Washington, D.C., who did not take part in this research, said in a review of this work.

The scientists detail their findings in the Aug. 9 issue of the journal Nature.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter