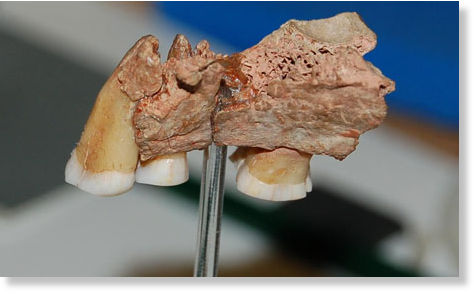

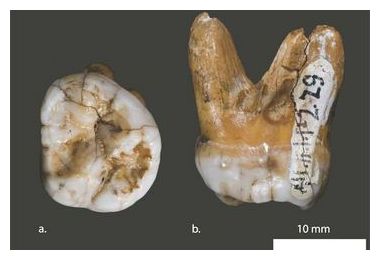

© Stefano BenazziA baby molar tooth from what is believed to be the remains of the first European anatomically modern human.

Europe's earliest known modern humans existed around 45,000 years ago in a southern Italian prehistoric cave, according to new research.

The discovery means that members of our own species have been present in Europe longer than previously thought, sharing turf with Neanderthals for at least 5,000 years.

"During this time it is very likely that some contact must have been achieved, but there is no direct evidence for it," Stefano Benazzi, a physical anthropologist at the University of Vienna, told Discovery News.

He explained that "Neanderthals must have survived until about 40,000 years ago."

Before the findings of Benazzi and his team, the first known modern humans in Europe came from Romania and dated to 40,000 years ago. Early Upper Paleolithic modern human cultures are documented in the Near East to about 45,000 years ago, which previously left a gap of 5,000 years between these Homo sapiens and the ones from Romania.

"With our findings, the gap is filled," said Benazzi, whose research was published this week in the journal

Nature.