Tipped off by Don in advance, I was fortunate to be able to join the team's research trip to the southern coast of England last summer. The white cliffs of Dover, subject of a memorable song from World War II, were also the setting for a much earlier clash of civilizations. Along this very shore, Julius Caesar first landed with two legions of Roman soldiers in 55 BC.

Caesar, in his first-hand account of the invasion, carefully noted the phase of the Moon, the approach of the equinox, and above all the unexpected ocean tides his fleet encountered. So it's a simple matter for any astronomer to determine the precise date of the invasion, right?

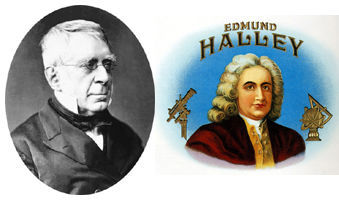

Wrong! No lesser astronomers than Edmond Halley and George B. Airy carefully studied the astronomical aspects of 55 BC in hopes of letting historians know the exact date and location where Caesar and his legions came ashore. But Airy and Halley disagreed with each other. And what's more, they both got it partly wrong, as Olson's Texas State team found out on their research trip.

What Needed to Be Determined

There were two top uncertainties to answer about the ocean currents when the Roman fleet arrived off the white cliffs of Dover:

(1) Which way was the current flowing on the traditionally accepted invasion date on the afternoon of August 26 or 27, 55 BC?To address the first question, our group went to the coastal town of Deal, the area historians have long believed to be the Roman fleet's eventual landing spot because it's roughly seven miles north of the stretch of white cliffs Caesar says he first encountered. That beach is indeed "open and flat," just as Caesar described. I noticed it wasn't sandy at all, being thickly paved with golf-ball-size pebbles its entire length, and wouldn't have been an easy place for Roman warriors to scramble ashore as they dodged a hail of spears and arrows from Britain's hostile Celtic tribes.

(2) Which way was the current flowing on an invasion date four days earlier, one that the Texas State researchers had already started to focus on?

To address the second question (the current's direction on the revised invasion date, August 22 or 23), we chartered a sightseeing boat that normally takes tourists around the Dover inner harbor. The skipper agreed to take us well beyond the breakwater, into the open Channel and northward along the white cliffs. To view my not-quite-ready-for-YouTube video clip as we pulled away from the Dover dock, click here (QuickTime player required).

Once we were out in the open sea, the skipper turned off the boat's engine. Kellie and Mandy began noting GPS readings and times, crucial data for determining the current's rate and direction by the drift of our boat. And yes - we were drifting northeast toward Deal. So on that afternoon, with lunar conditions so nearly matching those of 55 BC, the Roman fleet would have had no trouble making its way along the coast toward Deal.

I don't know about the others in our group, but I was starting to feel a little queasy as our small boat bobbed around in the choppy seas. I was glad when we got back ashore at Dover. The Roman fleet, its mission only just begun, had no such option.

For more more about the Texas State researchers' findings, check their press release as well as the August 2008 Sky & Telescope.

So You Never Knew All This About Caesar?

Time was when all high-school students translated Caesar's Commentary on the Gallic War in second-year Latin class. You know, the famous narrative that begins, "Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres...." The other night I dug out my old textbook. (And Mr. Dalton, if you're out there, I saved a great caricature of you that was surreptitiously drawn by a fellow classmate of mine back in 1961!)

Flipping those old pages to Caesar's Book IV, I saw that I'd underlined the words, "Eadem nocte accidit, ut esset luna plena...," meaning "That night, it happened that there was a full Moon...." Caesar was from the Mediterranean, where there is very little tide, and he didn't know that true ocean tides have nearly their maximum range whenever the Moon is full. As a result, his invasion fleet faced unexpected challenges as they looked for a suitable landing beach on the British shore.

Picking up on subtle astronomical clues like these has been a hallmark of the many projects undertaken by Don Olson and his Texas State researchers for past articles in Sky & Telescope - whether in a well-known painting, the original marathon, or a famous photograph by Ansel Adams.

Located less than 30 miles from mainland Europe, modern Dover is an important seaport. An abundance of harbor lights, designed to help maintain security, has also made this one of the most light-polluted cities on Earth. Roger Sinnott The Roman army's historic landing on the coast of Britain in 55 BC involved perhaps 100 ships and 10,000 men. But this was a rather limited incursion, by Caesar's own standards. Buoyed by the sensation his exploits caused back home, Caesar returned to Britain the following spring (54 BC) with an invasion fleet perhaps 10 times larger. It was like a D-day in reverse.

Caesar's crossing of the Channel, nearly 21 centuries ago, would alter the course of British history forever.

Joseph Conrad,

Heart of Darkness,

Chapter 1, excerpt,

(Scene: Guys sitting in a darkening boat, waiting for the Thames tide to turn.)

"And this also," said Marlow suddenly, "has been one of the dark places of the earth."

(Snip.)

His remark did not seem at all surprising. It was just like Marlow. It was accepted in silence. No one took the trouble to grunt even; and presently he said, very slow-- "I was thinking of very old times, when the Romans first came here, nineteen hundred years ago--the other day. . . . Light came out of this river since- (snip). But darkness was here yesterday. Imagine the feelings of a commander of a fine--what d'ye call `em?--trireme in the Mediterranean, ordered suddenly to the north; run overland across the Gauls in a hurry; put in charge of one of these craft the legionaries,--a wonderful lot of handy men they must have been too--used to build, apparently by the hundred, in a month or two, if we may believe what we read. Imagine him here-- the very end of the world, a sea the color of lead, a sky the color of smoke, a kind of ship about as rigid as a concertina-- and going up this river with stores, or orders, or what you like. Sandbanks, marshes, forests, savages,--precious little to eat fit for a civilized man, nothing but Thames water to drink. No Falernian wine here, no going ashore. Here and there a military camp lost in a wilderness, like a needle in a bundle of hay--cold, fog, tempests, disease, exile, and death,-- death skulking in the air, in the water, in the bush. They must have been dying like flies here. Oh yes--he did it. Did it very well, too, no doubt, and without thinking much about it either, except afterwards to brag of what he had gone through in his time, perhaps. They were men enough to face the darkness. And perhaps he was cheered by keeping his eye on a chance of promotion to the fleet at Ravenna by-and-by, if he had good friends in Rome and survived the awful climate. Or think of a decent young citizen in a toga--perhaps too much dice, you know--coming out here in the train of some prefect, or tax-gatherer, or trader even, to mend his fortunes. Land in a swamp, march through the woods, and in some inland post feel the savagery, the utter savagery, had closed round him,-- all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest, in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men. There's no initiation either into such mysteries. He has to live in the midst of the incomprehensible, which is also detestable. And it has a fascination, too, that goes to work upon him. The

fascination of the abomination--you know. Imagine the growing regrets, the longing to escape, the powerless disgust, the surrender, the hate."

(snip.)

But these chaps were not much account, really. They were no colonists; their administration was merely a squeeze, and nothing more, I suspect. They were conquerors, and for that you want only brute force-- nothing to boast of, when you have it, since your strength is just an accident arising from the weakness of others. They grabbed what they could get for the sake of what was to be got. It was just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale, and men going at it blind--as is very proper for those who tackle a darkness. The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. . .

Read Heart of Darkness! (All of Conrad’s works are downloadable for free online.)

R.C.