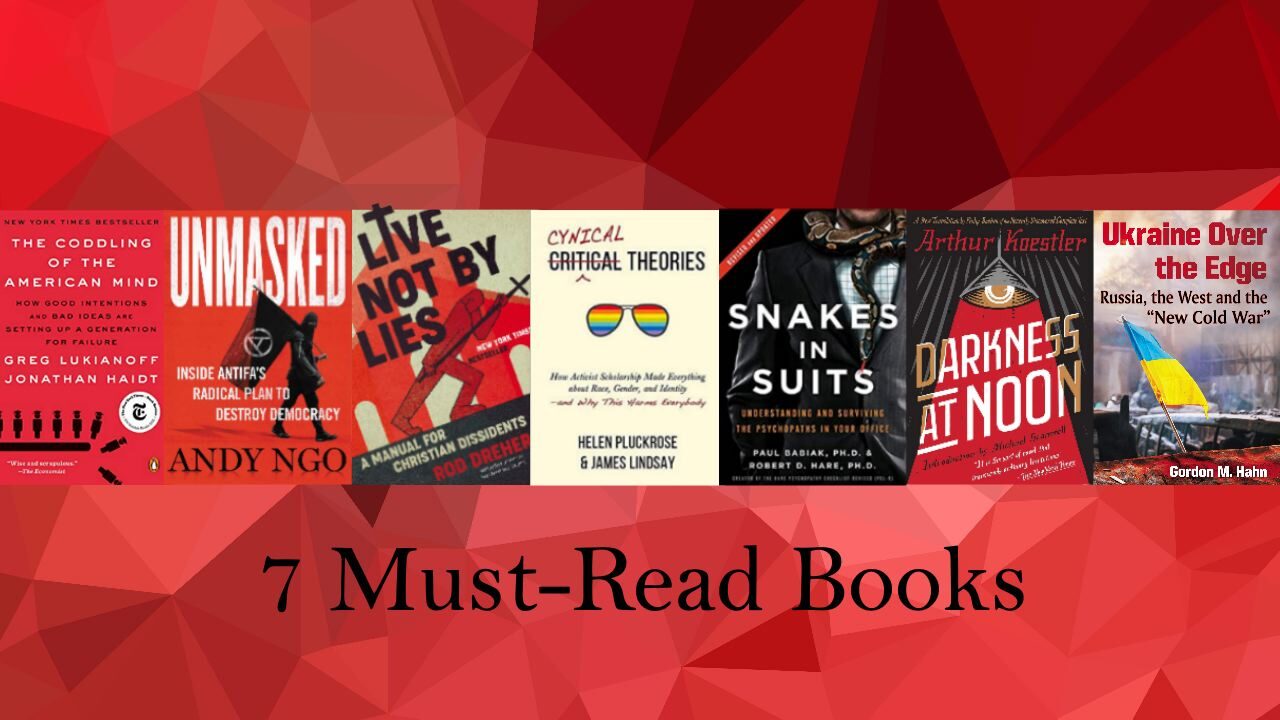

- The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure

- Unmasked: Inside Antifa's Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy

- Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents

- Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms Everybody

- Snakes in Suits, Revised Edition: Understanding and Surviving the Psychopaths in Your Office

- Darkness at Noon: A Novel

- Ukraine over the Edge: Russia, the West and the New Cold War

Running Time: 01:06:03

Download: MP3 — 60.5 MB

Here is the transcript:

Harrison: Hi everyone. Welcome back. Today we are going to be talking about some resources you can use to figure out and understand what's going on in the world so you can make sense of the madness. It's something we've been trying to do these last few weeks of the new year.

So I want to bring up some of the books that we've been reading again, maybe offer some online sources you can go to, some people on Twitter, maybe some YouTube channels, but with the focus on seven books that have come out in the last two years. I believe only one was published in 2018 and the rest are from 2019, 2020 or 2021 so maybe a bit over two years. We've talked about a few of them on the show before but I thought it would be handy to have them all in one video and as a reminder maybe you either missed the video where we talked about a specific book and have forgotten about it, this can be a reminder that you might want to read this book.

To start out with we'll take a quick look at the latest one. We haven't talked about this one yet; it just came out. It is Unmasked: Inside Antifa's Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy by Andy Ngo. I've been looking forward to this book for a while. Surprisingly, there aren't very many good books on Antifa out there. Of course you can go on Amazon and get the Antifa handbook or whatever it's called, the manifesto and a few other kinds of things but there's really only this one as a journalistic account and an academic one by a sociologist. His name is Stanislav Vysotsky. I've got that one too. I haven't read it yet but maybe we'll talk about that one. Apparently he did a bunch of interviews and even on-the-ground stuff, talking to antifa members to try to get an insider sociological perspective on it.

So Andy Ngo references that book at least once in here, but we'll talk about that one if it's any good. This book starts out with Andy Ngo's journalistic overview of the events of pretty much the last year, the black lives matter and antifa riots and protests that went on, his background, the infamous event that launched him into the wider public sphere was when antifa attacked him in I think 2018 and sent him to the hospital, basically a bunch of people beating him on the street and no one was held accountable which is a pretty common occurrence. He details the amount of violence and property destruction of course and the few murders involved, killings, and how little accountability there is for all these antifa guys.

Anyway, I just started reading this one. I haven't gotten all the way through it but already it's pretty eye-opening, even if you followed the events like I did and read most of the news stories. It's good to have them all in one account. And then he gives a history of the movement itself. One of the bits I'm looking forward to that I haven't gotten to yet is documents from inside the organization that reveal how they operate, what their plans are and that kind of thing. He talks about CHAZ and how he infiltrated CHAZ and was living there for a week or two until he was outed and had to get the heck out of there because, if you don't know, antifa regularly calls for Andy Ngo's death on Twitter, in graffiti. Once you realize what they're all about, you can understand why you'd want to be careful because they are not very great people, to say the least.

But the reason to read this book isn't just for an inside look at a group like antifa and what they're doing, but there's a wider significance to what's going on and why they exist and what it says about what's going on in the United States.

In Ponerology, which is the book that holds all of these books that I'll mention together, he talks about ponerogenic unions as he calls them, or ponerogenic groups and these are groups that start for arguably a good reason. At the very least they can start out with noble intentions and over the course of years that good intention and that original ideology, the values and the aims they have, get twisted and distorted over time. In the previous few weeks we've mentioned this and I've said that this even happens when the original ideology is bat shit crazy on its own. The same sort of thing happens, but with a group like antifa, this is one of the sick, devious things about it. The original ideology is anti-fascism.

So who can be against anti-fascism, right? And that's what they capitalize on, the fact that no one wants to be a fascist because obviously fascism is something most people don't want to be, practically all people. So they are able to set up a dichotomy of either "You're with us or you're against us. You're either an anti-fascist or a fascist. So if you don't agree with our perspective, our ideology, our aims and goals, if you're not explicitly supportive of us, then you are what we are designed to fight against."

That follows a standard pattern. One of the things that Lobaczewski points out is that when you have an ideology like this that has been perverted, that has gone off the rails to some degree, the reason that has happened has been because of the growth within the ranks of people essentially with personality disorders. He calls it a ponerogenic union, as I mentioned, and distinguishes between two types of ponerogenic groups, that is groups that lead to the development of and genesis of social evil, criminal evil, that kind of thing. He distinguishes between a primary and a secondary union.

A primary ponerogenic union is like a gang, a mafia, the mob, a group of bandits, a tightly knit group of people with a criminal goal. Most societies or pretty much everyone in a given society sees those groups as criminals and doesn't support them, wouldn't elect them into office, for instance, if they ran as a political party. But you also have these secondary unions. Secondary unions are the ones with social aims and goals and an ideology which people in general, or at least a large segment of the population, would and do support.

So if you have an ideology like anti-fascism, naturally people just seeing the name, hearing the outer layer of propaganda would say, "Okay, that's a good thing." You can get pretty massive support if you are hiding behind a good cause. But as a group has more and more pathological individuals, people with personality disorders, then that's what shifts the inner dynamics of the group so that that ideology becomes a mask over a criminal enterprise.

So it would be like the mob running on the democratic ticket or the republican ticket. They have the power of not only tradition in that case but of the support for them from a large percentage of the population which acts as cover for something else they want to do. It resembles a typical politician in the sense that they have what they say to the public, what they want to do, and then what they actually want to do. But there's an even more sinister element to it because in a secondary ponerogenic union, their goals are to achieve political power to radically change society so that they can do whatever they want, so that they can reorganize society to benefit them in their own interests.

You can look at fascism and communism in the 20th century to see how that historically plays out. When a group like that takes political power there is a radical restructuring of society and as James Lindsay likes to put it, humanity, society, gets put through the meat grinder, through the blender. That's typically what happens.

So when you look at a group like antifa and the amount of support - whether explicit or implicit, tacit - and the cover that is run for them by mainstream politicians and then you look at what they actually do and how they do it, they are essentially a criminal mob that is hiding behind an ideology of antifascism and using that as a way to radically restructure society and, if they had their wish, tear it down completely to replace it with their version of a utopian vision.

Adam: I don't want to jump in and sidetrack this too much, but it's an interesting facet of wokeism in general but then specifically the antifascist movement where it almost seems from the get-go like a ponerogenic union. It's almost a primary in a sense or at least very close to, by the time it has already come onto the stage and doing all these different things.

Harrison: That's why I'm interested to read the history of it because I don't know the total history of it yet, but it started in Germany I believe, in the 1930s I think, as a communist reaction to the rise of the Nazi party. So it has had almost 100 years to evolve and it could even be that by the time its American branch started, it was already far gone. I mentioned I did have Vysotsky's book on antifa. I did read the first few pages of it and like any good sociologist - I don't know if he's a very smart person yet - but he presents the scientific, academic view. He says "These are their goals. Their goals are antifascism. So their goal on the streets of America is to fight fascist elements, on the far right, etc."

So that's their explicit goal and their explicit ideology. What Vysotsky hasn't mentioned but which Andy Ngo and any number of commentators on antifa point out is, what's the definition of fascism that they're using? Their definition of fascism is either you're an anti-fascist like us or you're a fascist. There's no in between. So anyone who doesn't agree with them is a fascist, whether or not you're a fascist.

Adam: Yeah.

Harrison: That's how all of these word games work, like misogynist, racist. There are real misogynists, real racists. And then then there's everyone in the middle that can be called that because they don't agree with a tiny radical fringe group - well they're not so fringe anymore - who have massaged the language in such a way that practically everyone who isn't them can fall under that label.

So if you don't agree with antifa, if you don't agree with their methods maybe, then you could be a fascist too. Just like I mentioned when he was in CHAZ, one of the antifa people pointed him out. He's got the picture of her pointing at him. I think she said something like, "That's Andy Ngo. He's a known fascist", something like that. "Let's get him." Andy Ngo's not a fascist, obviously, but to antifa he is. To antifa, anyone who exposes or criticizes them is fair game.

Adam: It's interesting too that - I think it just came out today - where the female lead publisher for the book...

Harrison: His editor.

Adam: ...yeah, his editor got fired for simply having conservative viewpoints which of course has been redefined along these political word game lines to be that she is a fascist but that's just because they massaged the word and not because she actually is. So it's an interesting thing and points to the fact that we should read this book because they obviously don't want it to get out.

Harrison: And in Portland where Ngo is from, there's a famous book store, Powell's, and when the book was about to be released there were protests, calls on Twitter for them not to stock this book, not to sell this book. The book store had to shut down for a period of days because of the protests and of course saying "Protesting this book store for potentially selling this far right, fascist, racist book," or something like that. It's complete nonsense. It shows that they don't want people to read this book.

Not only do they not want people to read it, it's more than that because they know people will read it. It's just a statement that they can use their power to shut down this book store and to stop them from selling this book by one of their declared enemies. And Andy Ngo is one of their enemies. You can see why, because he does expose them. He exposes what they're really like. Maybe I'll read a couple of things. This is in the CHAZ chapter. I'll just read a paragraph.

"One glaring blind spot in the mainstream media coverage of CHAZ was how the space gave platform to violent extremist ideologies. Reports about CHAZ's political agenda focused shallowly on racial justice and defunding the police rather than its explicit calls to kill cops and overthrow the government. Hundreds of graffiti messages and images lined the zone showing dead pigs wearing police hats. One of the messages read, 'No work. No cops. End this stupid F-ing world. Voting keeps you tame. All politicians are the same.'"I like that one.

"They were handing out a booklet titled, 'Against the police and the prison world they maintain.' It features short essays on why police, capitalism and the state must be destroyed by any means necessary, including through violence. One section explains how the media are enemies used to pacify revolutionaries. The booklet reads, 'Our contempt for the media is inextricable from our hatred of this entire world.' {laughter}?Adam: Jeez!

Harrison: Kind of the definition of psychological misfits.

Adam: Yeah.

Harrison: Total misanthropy, a hatred of humanity. They want to 'tear the f-king world down', the entire world is against them. And, where does that come from? What have we learned over the past few weeks with all of this other stuff that we've been looking at, especially James Lindsay's recent article, is who views the world like that? The world is evil? Well, most people who come to those ideas on their own, who don't get them brainwashed into them by other people are people with certain types of personality disorders. The world is out to get them. The world is inherently flawed in such a way that they cannot function in this world. Well why can't they function in the world? It's because they don't fit inside of it. The world isn't set up in such a way that they would or could be happy.

Adam: Yeah, like you were saying, it's an extremist viewpoint. The only way a general more or less normal person would come to that conclusion is through brainwashing because if you're looking at it from a normal person's viewpoint, there's a lot of things that are screwed up but it's not a fundamental nature of reality itself that it is against you, unless you have some severe psychological trauma.

But if you're on the other side of the spectrum from the normal person and you are completely pathological then yes, the world is out to get you because society wants to find out who you are so they can selectively put you in a place where you can't do harm to the rest of society.

Harrison: That's why a couple of times in the last month or two I've made the comparison to serial killers because it really is. The mentality of a group like this is the mentality of a serial killer. First of all they have to put up this mask. They have to hide from the world and they do that with their black block, their masks, to try to avoid exposure whenever possible, even though even when they are exposed, nothing happens to them. But they have to use, again, the ideology as a mask to be able to pull the wool over the eyes of the people who aren't willing to put in five minutes of research to find out what's really going on or just watch them destroy city blocks.

Adam: They need that cover, that sheep's clothing to pull over the people's eyes. How did Lobaczewski put it? They have to romanticize the things that they do in order to justify them, but when you remove the romanticization, when you do the strip tease, you reveal the pathology for what it really is.

Harrison: Right. That's a good passage in there. He said something like that and then that's a painful process, even for a psychopath because when a psychopath's mask is revealed and they're exposed and people know who they are, they can't hide anymore. That's usually the only time that a psychopath will commit suicide, when he knows...

Adam: The jig is up.

Harrison: ...the jig is up. But Lobaczewski points out that it's not just psychopaths that are bothered by that, that normal people too, have a negative reaction to having an ideology like this exposed. It provokes a bit of cognitive dissonance, I guess you could call it, to have the romantic notions stripped away and to see the bare pathology underneath.

So people don't want to know the truth. It makes them uncomfortable on a very fundamental level, to see a group with an ostensibly good and decent ideology exposed as a bunch of raving criminal psychotics and psychopaths. It's uncomfortable. It's disconcerting. But that's really what's going on. Antifa is not an antifascist organization. They are NOT. There's nothing antifascist about them. It's in name only. I'll give them that.

So to expose them as a bunch of hoodlums essentially, even makes ordinary people uncomfortable because they want to hang onto that vision of antifascism. It's the same thing with communism in general. Even today you have communist apologists who make excuses for any of the communist failures of the 20th century. 'I don't see what the problem is.' They're a bunch of idiotic psychopaths who did untold damage to their own people on the entire planet and yet the people who are so uncomfortable about - this is just a pet peeve - the people who are so uncomfortable about exposing the nature of the people behind communism, put it that way, are totally willing to point out the totally inhuman nature of imperialist wars, the western world, NATO and the United States, killing hundreds of thousands of people.

Maybe it's the ideology thing because as much ideology as there is behind the American government or the western world, they don't have AN ideology in the sense that the communists did and do, in the sense that antifa does. So maybe it is that element of the ideology that acts as that cover so that people, even critics of western imperialism who you'd think would say, "Yeah, the communists were really evil too even though I hate the western world", but no, there's something about communism, "I don't want to make fun of it" or "I don't want to criticize it" because they just want a better world. They just want to make the world a better place.

Adam: And I think that's maybe where some of this comes from within the west. It's an aspect of liberalism within the west where we give each other a lot of rights. We give each other property rights and due process of law and all of these things. One of the fundamental ideas is that we assume the best in people and so whenever you present an idea, one assumes that you're actually trying to do good. I think that there is a lot of internalization of this idea and that could be why there is this revulsion to taking that position that this isn't about making the world better. Period. Full stop. Get over it.

Harrison: I want to try to figure that out in regards to a massive war. If you look at the Iraq war, because you could make an argument - and of course people have made arguments that war is good for various reasons, that war is making the world a better place even though it's hell while you're doing it. But I think maybe the reason that that doesn't apply in that situation is because war and its destruction are obviously not, and can't be rationalized or an excuse for them can't be made by saying that it is an unintended consequence that a whole bunch of people die. When tens of thousands of people die you can't say, "That really wasn't what we intended when we invaded that country and got into a massive war with them."

So it's blatantly evil, the level of mass destruction. But with an ideology, you can say, "Well, we were TRYING to make things better..."

Adam: We TRIED.

Harrison: "We tried. It just didn't work out very well and millions of people ended up dying. But we didn't mean for that to happen so cut us some slack."

Adam: So you can have it from two sides too. You could have the people within the party, let's say, who say, "We really did try but those darn fascists, kept screwing stuff up."

Harrison: The counter-revolutionaries.

Adam: "The counter-revolutionaries. They just kept throwing wrenches in the works." Then from the other side, the apologists I guess you could call them, would just make excuses like, "They tried but he wasn't really as smart as he needed to be. He couldn't have foreseen this, that or the other situation coming down the pipe" or whatever.

Harrison: But really, they just had good intentions.

Adam: Yeah.

Harrison: I guess anything is excusable if you had...

Adam: Good intentions.

Harrison: ...good intentions. It's harder to make the case for good intentions when you invade another country and get into a massive war with them. So maybe that explains that.

Okay, enough of that book. We'll get through a few of these in a quicker fashion because we've already spoken of them but I just wanted to remind you of them. But first, this one I mentioned last week, I think. This is Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon. This book, of course, did not come out in the last few years. It was originally published in 1941 but this edition came out in 2019. For anyone who hasn't yet heard of this book, if you like 1984, Animal Farm, this should probably be on your bookshelf right next to them because it's also a classic but less well known than Orwell.

But this is a new translation based on a new manuscript that was discovered in 2015 in Germany, so of the original German manuscript. If you've already read it, that's an excuse to read it again in its most pristine form, if not in German, and if you haven't read it, then it's a good chance to check it out and read it for the first time. If you don't know anything about it, it's a very thinly veiled account of the show trials of the 1930s where a lot of the original communists - I guess you could call them the first wave of communists - were eliminated by Stalin. I'll just leave it there. It's a great book so check that one out.

So if you want an idea of how things were in the past in novel form, then check that one out.

Again, check out Cynical Theories by Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay. Very worth it for understanding the ideology that's going on, the background, that has led to the postmodern elements of the philosophy that have led to critical race theory, social justice theory, essentially what you see whenever you turn on the TV or read the news or enter a university today or any corporate environment. If you want to understand the entire world then you can read this book.

Adam: I've only read part of it, but I got the same impression of postmodernism and critical theory that I got from what we were talking about earlier with antifa's statements and all that stuff and it being almost like a primary ponerogenic union at the onset. So I was wondering about that, but now that we've talked about it a bit, the ideas actually start with the enlightenment, so it has actually had a long time to adapt and get transformed and ponerized to get to the 1960s and Derrida.

Harrison: It's hard to say what a lot of the original postmodernists would think if they were transported into the present or 10 years into the future. I think that they would probably be horrified too. It wouldn't be immediately apparently to them that they were responsible for it because that's the way that cynical philosophies tend to work. You get a very smart philosopher who comes up with these ideas that are great in his own head even if they make sense to very few other people, that then have their effect on the world. And they have that effect because they are at odds with reality. When you have a philosophy that is at odds with reality, it will clash with reality and that clash usually takes the form of massive destruction, death and subjugation.

A lot of these philosophers are academics writing their tomes from their university office desks. A lot of them weren't on the streets working behind the scenes trying to topple governments and defund the police. They had lofty ideas. It's their influence on the actual movers and shakers, the people on the ground, that gives them any kind of power. If they just wrote their books and no one read them, nothing would happen. These guys are just academics.

I don't have all the details. I wouldn't be able to give a comprehensive account of why it actually happened, but through their influence on their own students and being widely read, that influenced an entire culture and created something even wider. You can see the good intentions behind even a lot of the postmodernists and a lot of the early disciplines that led to the caricatures that we see today in women's studies, race studies and all these kinds of things. You can see the motivations behind them which explain why people can support them today, because they were founded in something that everyone can kind of get behind, which is 'don't treat women like animals', 'don't judge people based on the colour of their skin', and 'people should be treated equally', or at least not be unequally treated based on race or gender or whatever.

Adam: Yeah. And in some sense, rules are arbitrary so we can play with them. It's not unsanctimonious to question certain rules and things. One of the presentations that I saw of a French postmodern film and the effect that that had on the movie industry is pretty profound because before the French postmodern film era, things were very structured, very rigid. Whenever somebody was traveling you had to show them traveling and the French postmodernists were like, why? Can we not just assume that they'll get it? So they did all of these playful things, playing with the rules and broke down the structure in a good way. So it did have some useful utility there. But then the other side of that coin is when you just question everything to ad infinitum and it's like a two second clip of an apple just sitting on a table and it's supposed to be profound and it's just an apple.

Harrison: It's kind of like dissonance in music. That's the way I see postmodernism. It's the devil's tritone, the devil's interval or just very atonal aspects of music, which if you know anything about music, music needs a little atonality, a little dissonance in order to make it work. That's how you get a coda, the resolution to a song. But there's a degree to it. So of course the postmodern music to totally deconstruct the entire structure of western music, then you get stuff that most people don't consider to be listenable because it's so atonal and so dissonant.

That would be the equivalent of an apple, but maybe a cubist apple that's refracted through something so it's just a blob on the screen and you can't tell what it is and you show that for 30 hours or something. So there's a spectrum of the application of postmodernism to something but, like you said, there's some good that comes from it where you can be playful with it, experiment and find new ways of doing things so that you don't need to show people traveling from place to place all the time. People will get it.

So that's one of the ways that I see postmodern philosophy. While it's wrong in so many ways, everyone I think will agree that postmodernists can make valid criticisms a lot of the time. I don't see the original postmodernists as these evil sons of bitches like I would a lot of other people, but they were wrong about very important things and the influence of their ideas has led to the things that are much worse. Some of the primary things they were wrong about is the complete anti-realism, that there's no possibility of objectivity. Or they have this weaselly way of getting around that. If you take their philosophy to its logical conclusion, it is totally relativistic and there's no objective truth. But they'll say, "But that's not what I'm saying. Anyone who makes a truth claim, who claims that something is true, that that can't be interrogated without looking at the context that goes into their truth claim and all of the socialization and extraneous ideas, oppression and power that goes into that statement."

Okay, so is it true or not? That's what most people are concerned about. Well, is it true or not? Yeah, there might be some power dynamics involved. We can look at those, but is it true or not? That's the primary thing that most people are involved in. Can I eat this?

Adam: Yeah.

Harrison: Can I eat this? Will it sustain me for the next day so I don't die?

Adam: Is it raining outside?

Harrison: Right. Is it raining outside? You can just imagine these postmodernists. "Is it raining outside?" "Well I have to question the power dynamics behind your statement."

Adam: Your assumptions.

Harrison: Yes. So a lot of it is really just language games. But now you see, even if they would claim, "We're not really anti-realists. We don't REALLY believe that 2+2=5 or that it's not raining outside when it clearly is," now you can see the result of that kind of relativism and that kind of antirealism in the world.

Adam: Look around.

Harrison: Just look around. Is that enough on cynical theories? I just wanted to say this focuses on the postmodern elements. What they cut out of the book because it would have been too long is the actual critical theory guys, like Marcuse and Gramsci before them and Horkheimer and Adorno and all that. So if you want to learn a bit of that then you can just go to New Discourses and listen to some of James Lindsay's podcasts and follow him on Twitter because that's where he's talking about a lot of that stuff that wasn't in the book.

Adam: So I guess what I was trying to get at earlier then was that distinction - not even a distinction - there's the playfulness of the postmodern ideas but it's when they started to get into the fundamental assumptions of there being an objective reality and questioning it without questioning it? That's when I started to think, "Something's not right here."

Harrison: Yeah, they're totally detached from reality in a certain sense and a lot of them motivated by some kind of...

Adam: Were they just trying to be cool?

Harrison: That's the way I see it. They're trying to be smart. They see themselves as having these great ideas, which when it comes down to it aren't really that great. But they write in such a way that they appear to be very smart because they are massive intellects but they're so massively intellectual that a) their work doesn't make sense to most people and b) it pretty much makes sense only to them because whenever their critics try to understand it then they can always point out how their critics misunderstand them because it's not understandable. It even gets to the point where one of the postmodernists - I think it might even be a modern postmodernist - says that to even attempt to come up with a definition of postmodernism would make it not postmodern. So it has to be undefinable.

So you get trapped in this realm of utter subjectivity and inability to know anything. It's totally anti-epistemological. You can't know anything. You can't even define what postmodernism is because to attempt to define it would be to use a modernistic tool of reason and rationality to try to explain this something. It's like this totally abstract creation that has very little connection with the actual world. But when you strip away all of that over-the-top complexity and intellectualism, you can find some decent stuff, some things that actually make sense, but it's just so bogged down with arcane, baroque reasoning and language, why bother even reading it? That's kind of where I'm at.

Adam: They came up with some interesting ideas and some good criticisms and then let their self-importance get the better of them and then they just kept devolving down further and getting more entrenched in it and then here we are.

Harrison: It reminds me of a class I was taking on the study of religions in university and we were working through a textbook about all of the different approaches to the study of religion in the academy over generations. So we had sociological, psychological and historical perspectives. Near the end of the book we only had a couple of lectures left but the professor gave us a choice: "Do you guys want to do the postmodernism chapter or the feminism chapter?" The majority of us chose the postmodern one. He said, "Okaaay!" He gives a lecture the next class and he says, "So, I bet now you would have liked to have done the feminist one, huh?" And we all agreed because the feminist one actually made a lot more sense than the postmodernist one. It was totally off the wall, totally ridiculous.

But that's what the kids like these days I guess. Or that's what they liked in the 60s and the 70s, the 80s and the 90s. Now Foucault is the most cited scholar ever, which is quite funny. But anyway, that's Cynical Theories.

Next one, Live Not By Lies. We interviewed Rod Dreher on the show so we'll include a link to that because there we pretty much say everything that needs to be said about this one. Recommended.

Now we haven't really talked about this one on the show, I don't think. I was looking through it and looking through my notes for it the other day so I wanted to mention it: The Coddling of the American Mind - we've mentioned Jonathan Haidt before. He wrote this with Greg Lukianoff - How Good Intentions (there it is again) and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. This is primarily inspired by and about the situation in universities these days, what's going on in the universities because there's a lot of crazy, crazy stuff that's been going on for the past 10 years or so which has roots going back even further and you can trace it back to the postmodernists and the critical theorists and all that fun stuff.

But there's so much in this book about what's going on. What's great about it is that it's presented in the context of cognitive behavioural therapy which is one of the most effective forms of therapy out there for people dealing with actual emotional problems and issues. The nutshell view of it is that what's going on in the universities - and not just in the universities, but in the wider culture - it's almost like anti-psychotherapy. All of the principles that work for how to deal with stress, phobias, aggression, negative emotions, all the things that actually work to get rid of those, the universities and social justice theory and practice do the opposite. It actually makes things worse.

So in the case of dealing with a fear of exposing yourself to that fear to overcome it and to get used to it...

Adam: Inoculate?

Harrison: ...inoculate, no. It's when you progressively get more and more used to something. I can't think of the word. So you expose yourself. If you're scared of spiders, you have it 20 feet away, 15, 10, let it touch you, etc., etc. You get closer and closer and at each step you deal with it and aren't overcome by your fear to the point where you can carry a spider in your hand and you're not afraid of it.

But in our culture it's "No, put it even further away. Let's all get together and scream and make it go further away." That screeching makes them even more afraid, more intolerant and have even more negative emotions which is probably not the safest and best thing to do. So if you haven't read this book, I highly recommend it. I like Jonathan Haidt's previous book The Righteous Mind too. I'll just give a glimpse of some of the ideas in here.

Part 1 deals with three bad ideas, three untruths as they call them, the untruth of fragility, that what doesn't kill you makes you weaker, the untruth of emotional reasoning, always trust your feelings and the untruth of us versus them, that life is a battle between good people and evil people. Those are some fundamental aspects of the worldview that is prevalent in university culture and everywhere now.

Along the way, a lot of great stuff, but it ends with prescriptions for what can be done about it, how to have better universities, how to raise kids better because parenting practices contribute a lot to this including the decline of play, the bureaucracy of safetyism. Good stuff. And while looking through here I noticed that there are a few good mentions of Marcuse that didn't stick out to me when I originally read it. I'm going to read something that they have from Regressive Tolerance. I'll read a couple of paragraphs.

"Marcuse recognized that what he was advocating seemed to violate both the spirit of democracy and the liberal tradition of non-discrimination. But he argued that when the majority of a society is being repressed it is justifiable to use repression and indoctrination to allow the 'subversive majority' to achieve the power that it deserves. In a chilling passage that foreshadows events on some campuses today, Marcuse argued that true democracy might require denying basic rights to people who advocate for conservative causes or for policies he viewed as aggressive or discriminatory and that true freedom of thought might require professors to indoctrinate their students."Here's the quote from Marcuse:

"The way should not be blocked by which a subversive majority could develop and if they are blocked by organized repression and indoctrination their reopening may require apparently undemocratic means. They would include the withdrawal of toleration of speech and assembly from groups and movements which promote aggressive policies, armament, chauvinism, discrimination on the grounds of race and religion, or which oppose the extension of public services, social security, medical care, etc. Moreover, the restoration of freedom of thought may necessitate new and rigid restrictions on teachings and practices in the educational institutions which, by their very methods and concepts, serve to enclose the mind within the established universe of discourse and behaviour."I don't think they include the quote here but in that same essay Marcuse essentially says explicitly that the implication of all of this is that we have to be totally tolerant of everything on the left and totally repressive of everything on the right. So the logical implication of that is that anything on the left which includes violence should be tolerated. Anything on the right, even if it isn't violent or extremist, cannot be tolerated because it will inevitably lead to violence and bad stuff.

So he says because the right inevitably leads to totalitarianism and fascism and all these things, that means that the left should be totalitarian and fascist to make sure that totalitarian and fascism never come about. That's essentially the logic of Marcuse.

Adam: Which is very comical. There was something in there that he...

Harrison: More crazy stuff that Marcuse said? Is that possible? {laughter}

Adam: Is it possible? I don't know! He said it nevertheless, but the idea of needing this repressive organ to stamp out certain speech in order to protect free speech undermines free speech so it can't really be called protection of free speech because you're whittling it away. That's another one of those aspects that has spread into the wider culture of shutting things down that you don't like and you could say you have good intentions for it because you want to shut down the white supremacists because you don't want more white supremacists. But that's not actually the way that you get people not only to not become white supremacists but also to convert away from white supremacy.

We've talked about the example of the black jazz player, a bassist I think...

Harrison: Piano player.

Adam: Piano player?

Harrison: I forget his name.

Adam: Yeah. I can't remember his name either. (Daryl Davis)

Harrison: Again! {laughter}

Adam: Where he went to white Klansmen meetings, sat there and befriended these people and just by simply as a black man, giving and showing them respect and talking to them, engaging with them as if they're human beings, he was able to convert some of the heads of the Klan away from white supremacism.

So obviously the way forward is to give them a voice, to let them air their grievances, let them share their opinions and then let other people understand where they're coming from and what they have to say so that way they can critique it themselves, realize how ridiculous it is and move on as opposed to further putting it into the dark corners where it then gets its own justification. It's like, "See? We're being repressed. That means we're obviously right" so then they attract more people and then they become more of a problem. So they're actually creating more of the problems that they say that they're trying to solve by creating the problems.

Harrison: Yeah. Two more books. This one. We haven't actually talked about this book on the show before. Snakes in Suits: Understanding and Surviving the Psychopaths in Your Office by Paul Babiak and Robert Hare. This book also came out several years ago but this is the new, revised edition that just came out in 2019. This is about corporate psychopaths.

So it was one of the first books to talk about non-criminal psychopaths. Cleckley, the original Cleckley, the greatest of all time...

Adam: Oh gee!

Harrison: Oh gee! He talked primarily about psychiatric psychopaths, so people encountered in psychiatric institutions and Hare, in his first book - Hare is the guy who developed the standard test for psychopathy, the psychopathy checklist - his first book in the mid-1990s, focused on forensic populations, so criminal psychopaths, psychopaths that were in prison.

So this book was the first one to be focused primarily on psychopaths in a non-forensic population, so in the corporate workplace. Just for that reason alone it's worth reading because psychopaths are not just serial killers or violent criminals. There are psychopaths on Wall Street and in corporations and this book is a good introduction to that concept and it has been updated with a whole bunch of the latest research to come out since this was originally published in 2006. So it's also worth reading. Is there anything else I wanted to say about this?

It's important because, as we say on every show, as we do every day {laughter}, we are pointing out that psychopaths are really important, especially to all these things that we're talking about, that psychopathy is instrumental and an essential part of what's going on with antifa, what went on with the communists, what's going on with critical theory, what's going on in the universities and why Rod Dreher had to write a book like Live Not By Lies. Why was such a thing necessary in Eastern Europe? Why were things so bad that people needed to have these groups where they could actually talk about, in this case, religion, and have a sense of solidarity with someone within society in Eastern Europe? Because this is the influence and the reach of psychopathy and what it does to people; not only what it does to people but what it can do to an entire country or wider than an entire country, an entire empire.

It has profound psychological effects on the people around them. This is true on all scales, whether it's interpersonally one-on-one if you have an encounter with a psychopath, whether in the workplace or not. That's why this book is essential if you haven't had that experience, to see what it's like, to see what goes on, to see what it is in a modern, corporate example. Of course it can happen in a romantic relationship or a family member or any other interpersonal relationship. But that dynamic and the traumatic effect, the stress effect on the person involved translates and scales to a macrosocial level. It can and does scale to an entire society in certain circumstances. So that's why you should read Snakes in Suits. Did you have anything to say on that one Adam?

Adam: No.

Harrison: Okay, then the last one. This is kind of the odd one out in these books but because it was published a couple of years ago and I really like it I'll mention it.

In order to understand what has been going on, on the geopolitical level, the wars we've been involved in that are still ongoing, the conflicts in the world and let's say the last four years of accusations - let's put it that way - Ukraine Over the Edge, Russia, the West and the New Cold War by Gordon M. Hahn. Back on our old show we interviewed Gordon about some of his previous books. He has written two books on Islamist philosophy in Russia, in Chechnya and Dagestan and so his first book on that subject was on terrorism in Russia. The second book was on the Caucasus Emirate Mujahedeen.

So this was the group of jihadists in Russia that developed over the years during, but mostly after the Chechen war in the late 1990s and eventually declared the Caucasus Emirate, an Islamic state in Chechnya and/or Dagestan, or one or the other, and declared loyalty to Al-Bagdadi and joined ISIS and went down into Syria and Iraq. So his book was on them and their organization and how that all played out and how they eventually went to Syria.

He's a Russia expert so this book is all about primarily the history of the conflict in Ukraine, everything leading up to the conflict in Ukraine, the revolution/coup in 2014, all the circumstances surrounding that. So I'd say if you don't really know, or if you THINK you know what was going on in Ukraine and what's been going on with Russia for the past seven years or longer, longer than that, then read this book because it's got all the background and Hahn knows what he's talking about.

This has got not only current events, it's got the entire history in summary form of Ukraine and Ukraine's relations with Russia, relations between the west and Russia, explaining everything that's going on. The way that it does relate to previous books that we've been talking about is that there's one section in here describing the neo-Nazi ideology in Ukraine, groups like Right Sector and their history and what they're up to. So in a short chapter it's a similar kind of look as the one Ngo gives to antifa in the first book we mentioned.

It's great to read as a contrast so when you see talk about the far right in the United States, which oftentimes just means anyone to the right Karl Marx, and you compare individuals who are called far right, like Andy Ngo, Jordan Peterson, anyone like that {laughter}, and compare them to what an actual far right group looks like, what they actually think and do - and of course there are some people like that in the states of course, but just not very many - to see what they're actually like, what's actually going on in Ukraine, who happen to be the people that the US government supported in the coup in Ukraine in 2014, it's a bit of an eye-opener, especially when you combine that with what went on in Syria for many years, the types of groups that the US and the west were supporting in Syria, what is it about the US military and intelligence supporting the far right and Islamist groups in foreign countries to overthrow the governments there?

Adam: It's an interesting development, like you said. They keep supporting all of these primary ponerogenic unions. It's very strange. They take over wide swaths of areas and infiltrate governments and wreck nations. It's just interesting that they just keep doing that over and over and here they are supporting antifa and black lives matter and critical theory and supporting all the most insane things I've ever heard in my life. It's just interesting! It makes you wonder.

Harrison: Yeah, I think there's something going on there. I think that's enough. That's plenty of books to read. All of you viewers should have that done by next week I suppose.

Adam: By tomorrow.

Harrison: We'll give them a week. Seven books, one a day, that's doable. So with that said, hope you enjoyed it, hope you get some reading done and we will be back next week with another show. So take care everyone.

Reader Comments

Read this book, The Decline of the West if you can get your hands on it ??

Or you can download it @ [Link]

RC

David Riesman was kinder: "over-conformist semi-automatons"

LOL

" And Merleau-Ponty makes it clear that the Moscow trials—and violence in general in the Communist world—can be understood only In the context of revolutionary violence. He demonstrates that it is pointless to begin an examination of Communist violence by asking whether Communism respects the rules of liberal thought; it is evident that Communism does not. The question that should be asked is whether the violence Communism exercises is revolutionary violence, capable of building humane relations among men."

[Link]

Sounds like a very smart person.

As for changing his critique, I'm just going on this:

Emma Kathryn Kuby, Between humanism and terror: the problem of political violence in postwar France, 1944-1962, Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University, 2011, pp. 243–4: "Merleau-Ponty provisionally defended Soviet “terror” in the name of humanism, writing that so long as the USSR’s violence was authentically revolutionary in its aims, it was justified by the fact that it was helping to produce a socialist world in which all violence would be eliminated. ... Yet about three years after it was published, Merleau-Ponty, too, decided that he no longer believed political violence could be justified by the purported humanist aims of the revolution."

Either way, all indications are that MP was a revolutionary utopian douchebag.

your projection of your insecurity is expected

Also, you are overstating your case to the point of damaging it, such as . . .putting things in terms of - whatever, like this: " Well, RC's an American and America faked the reason for a war with Vietnam, and therefore RC obviously is a natural gook killer" does not at all help your position; I bet that you know that.

RC

in 1948 Geoffrey Gorer described your society as an oral culture---the 1st stage in Freud's 5 stages of development. In deed in 1948 he found you to be so oral that only amerikans use food terms to address your lover's: honey, sugar, dumpling, cupcake, etc

The cultural historian Gary Cross examines how you are becoming ever more childish---too many proofs to mention

"standardization in music is immaturity". Immanual Kant

Mel Torme described everything in the USA as "3 chord manure"

"amerikans are the living refutation of the cartesian cogito ergo sum. amerikans do not think yet they are. the amerikan mind puerile, primitive lacks charact eristic form and is therefore open to any standardization". Julius Evola

As to 'everyone', well, not me and not HK, and not other SOTTites that I know. Thus that's facially incorrect and is another example of your routine overstatements that self-prove their inaccuracy.

You've studied at Wuhan? That's cool.

Your thoughts on the Cultural Revolution?

RC

But there's one thing, I never turn my head when I'm in a crowd, toward someone shouting, Hey Stupid !

"the people of north amerika accept a level of ugliness in their daily lives nearly without precedent in the history of western civilization"

Yuri Bezmenov

"no people are more entertained and less informed than amerikans (also Canucks). amerikans do not converse, they entertain each other. amerikans do not exchange ideas, they exchange images. the problem with amerikns/canadians is not Orwellian, it is huxlleyan---they love their OPPRESSION" Neil Postman

LOL

he attributed your misadventures in Vietnam and Iraq, both fully supported by 80% of amerikans to a particular culture and the "psychology of that culture"

LOL

one of many cults and fetishes in north amerika

"I did not understand Sigmund Freud because I was crippled by Cartesian ontological assumptions". JP Sartre

LOL

As re spelling, there's a reason for grammar - to make words easier to be written and understood. I ain't gonna gripe about anything other than you misquoting people by spelling what neither they nor the first (and all other) English translations have said. That's affirmatively recreating what they said, especially since 'Amerika' is inherently negative.

(Of course, perhaps you're in favor of making everything double plus simpler - why does that sound familiar?)

RC

"With your little bo-peep diploma." "The poodle bites, the poodle chewses/chooses." [Link]

RC

u r welcome! LOL

LOL

"Americans are ignorant and unteachable"

George santayana

My work is done here.

RC

hmm. if you 3 musketeers some time might find time for it, i would absolutely have loved an episode about; "what can we learn from famous people who were "proven" dead wrong".

- eg. why is it so that freud is still pensum for psychology students

- why is the so-called "stockholm-syndrome" still being used as a term/concept? (it did not happen the way it is so famously described)

- hmm. darwin?

- etc.

GREAT IDEA!

RC

However, I have a suggestion. Let us embrace the reality! US voters have elected a black Jewish lesbian for president, to save American peoples from imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, antisemitism.

We should help xer!

For instance, let us help the members of academia recognize and avow xeir white cis-male privilege regardless of xeir skin color, sex or sexual preferences. We all know now that race and gender are social constructs, and that universities, with their science and research, are among the foundations of imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. So, the faculty members cannot be other but white privileged cis-male oppressors!

It is frustrating as hell. I wish that these keystrokes could provide some answer, but we each know that ain't possible. All that is left if for folks like us to document, as best we can, what the fuck happened and why (as we perceive it), and Lord, please have mercy on this world - this sorry old and nigh worthless civilization..

R.,C.

RC

When a group takes over, it's nothing but STS all the way down.

RC

Such seems to be the ultimate conundrum of my life.

RC

Wise.

RC

"He who fights with monsters should take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you." - Nietzsche ( Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future (1886), Chapter IV. Apophthegms and Interludes, §146).

RC

************

Technocracy Rising by Patrick Wood scroll down to watch the vid by the author on this book [Link]

************

The Most Dangerous Superstition by Larken Rose a freebie... " Overview : In the following pages the reader will be taken through several stages, in order to fully understand why the belief in “authority” truly is the most dangerous superstition in the history of the world. First, the concept of “authority” will be distilled down to its most basic essence, so it can be defined and examined objectively..." .pdf here: [Link] Or audio if you like: [Link]

***********

Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology by Neil Postman Ultimately, reading this book reminded me that those who don't learn how to use technology will be used by it. [Link]

***********

Tower of Basel by Adam Lebor [Link]

"The world's most exclusive club meets every other month at 7pm on Sunday evening in a circular tower block whose tinted windows overlook Basel railway station. Its members include some of the most powerful men in the world. They are central bankers, who have come to Switzerland to attend the Economic Consultative Committee of the Bank for International Settlements, the bank for central banks..."

************

War Against the Weak by Edwin Black James Corbett said of this book; "...So, if you want to know your enemy, it is extremely important to understand this idea, its origins and development, and I know of no better single-volume exploration of the development of the American branch of this pernicious ideology than this book by Edwin Black." [Link]

RC

It's obvious that Lenin's early directive to the communists party during the Bolshevik Revolution, to infiltrate all spontaneous groups was very successful and has become their M.O. ever since.

As said, most groups start out with good intentions, take Greenpeace for example, protesting against the French government's nuclear testing in the Pacific, but infiltrated and deviated by the left (communists) to the point that it's Co-Founder quit. It now serves TPTB's eugenic agenda.

[Link]

'Opening the CIA’s Can of Worms' "...This is true. The corporate mainstream media are stenographers for the national security state’s ongoing psychological operations aimed at the American people, just as they have done the same for an international audience..." [Link]

“Since I entered politics, I have chiefly had men's views confided to me privately. Some of the biggest men in the United States, in the field of commerce and manufacture, are afraid of something. They know that there is a power somewhere so organized, so subtle, so watchful, so interlocked, so complete, so pervasive, that they better not speak above their breath when they speak in condemnation of it.” - Woodrow Wilson

Did you ever stop and wonder for a single minute if one man, Rockefeller, was really the single power behind standard oil? Ever hear of front men? Those are the ones meant to be seen.

How few ever wonder who TF really controlled the CIA and it's precursor?

No, people stop right there. They think they are super informed by knowing Rockefeller and the CIA. They try to hold the line there.

This suppression of conspiracy theory tactic, of trying to get people to fixate on operation paperclip, which is a limited hangout nothingburger, is also really over used. Ever hear of the Mossad Honeypot run by Epstein and other enemy foreign agents? How about how the whole world watched the FBI cover it up?

Oh, that's way too hot to touch. Let's talk about standard oil and operation paperclip. Why was Epstein's island named Little St James? What did the feds bury there with that heavy equipment? What Intel agency did Robert Maxwell and Mega group work for? Why doesn't anybody mention that they are all Mossad Oh yeah, there is the answer to all of it. Now let's go revisit those "anti-Semitic conspiracy theories" on currency ownership...

The invisible PTB is “The Black Nobility”, a few families that descend from a group composed of Venetian Nobility, certain Khazars, and Vatican leaders. They moved from Venice to Amsterdam, and from there to England. They control everything from the City of London, the Vatican, and Washington DC. Their financial administrators are the Rothschilds.

after Geoffrey Gorer examined the media in USSR and the curriculum in Soviet schools, he described the censorship in US media and schools as "ludicrous"

"amerikan academia is far more effectively censored than was Soviet academia". Georgi Durlugian

"censorship reflects a society that has no confidence in itself". Potter Stewart

"I know of no nation where there is less independence of mind and any real freedom of debate than amerika". Tocqueville

You sure dislike America - you remind me of people who hate Russians because "they were commies" but really it was because of social programming.

RC

your stupidity is unsurprising---the self uglified amerikan

The events being chronicled daily bear witness to this diabolical scheme while books usually cover different aspects of the plan like pieces of a jigsaw.

A book I'd recommend giving the big picture is 'Terrorism and the Illuminati, a Three Thousand Year History' by David Livingstone who has investigated the relationship between Islamic fundamentalism and Western imperialism. He explains the origins of all the occult sects, religions, the (ig)noble Bloodline families, various peoples and Empires that have, through a network of secret societies, been working for world domination. Starting with the Luciferian and up to Al Qaeda and the Rothschilds.

An author whose books I haven't read but would, if I didn't feel I've read enough, is Nesta H. Webster. 1)'Secret Societies and Subversive Movements'.2) 'World Revolution: The Plot Against Civilization' and 3)'The French Revolution'. I am sure they would all fill in a few gaps.

Also From Yahweh to Zion by Laurent Guyenot, and...

Political Ponerolgy by A Lobaczewski.

A few more books to add to the list.

R.C.

Whatever - as you? HA2? sez: let's not feed 'em, or such, which us chatting here is abstrusely kind of that, and certainly a waste of time for us. SO... How's things? (I won at pool.) (Absolutely love that otter guy! )

RC

Anyway, I've never seen that, so I stopped the highlight so that I can watch it sometime. Thanks!

Yes, I won. I usually do except when I first play some fat guy.

RC

RC

*When I was 15 I routinely walked over a mile down the railroad tracks,

barefoot, through the snow, uphill both ways to school.to my local pool hall bar. (I had an ID that said I was 25 and they had no pics on them and I had a solid mustache by then, so it was no worries.) A LOT less government then. See the AB.RC