In saying all this, I am by no means making a case for why Rhodes was great. The exact opposite is true, yet there are two sides of Rhodes, both of them imperialist, but both of them not widely understood. One side of Rhodes is relatively well known: he was an imperialist who was heavily involved in Southern Africa, including serving as the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony between 1890-96; he believed that English people were the master race; he was a diamond magnate who founded the company De Beers, where labourers were racially segregated during his time; various Rhodesian Africans colonies were named after him; he set-up a Rhodes Scholarship program at Oxford University that the likes of Bill Clinton went through; and Hitler reportedly admired him.

The Cecil Rhodes Secret Society

Yet, there is another side to Rhodes. This, more esoteric side, is unfortunately not so well understood, yet equally important to understand. Firstly however, it is important to establish that Rhodes had a long-term vision of creating a global system under British rule. In his first will written in 1877, when he was only in his mid-20s, Rhodes stated that he desired:

In other words, Rhodes wanted to create a global system so great, and control world affairs so perfectly, that no country or people could escape its domain. In order to achieve these aims, Rhodes, during a meeting on a cold February afternoon in London in 1891, founded a secret society that became known as Cecil Rhodes' Secret Society (Quigley 1981: 33-34). The secret society was to serve as a form of religious brotherhood based on the Jesuit model, and was to be devoted to the extension of the British Empire across the globe (Quigley 1981: 33-34). Rhodes had long-wanted to create such a society (Shore 1979: 253). He served as the leader of the group, with the two other founding members being the journalist and newspaper editor, William Stead, and the trusted adviser to Queen Victoria and King George V, Reginald Balliol Brett (Quigley 1981: 3). Alfred Milner, an influential British official and banker, who, for the record, was originally born in Germany, was accepted into the group shortly after the meeting (Quigley 1981: 3). Interestingly, the organization of the society was divided into an inner circle, called "The Society of the Elect," and at least one outer circle, called "The Association of Helpers," with this organizational structure designed to conceal the workings of the inner circle (Quigley 1981: 3)."The extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting ... of colonization by British subjects of all lands wherein the means of livelihood are attainable by energy, labour and enterprise ... the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British Empire, the consolidation of the whole Empire ... and finally, the foundation of so great a power as to hereafter render wars impossible and promote the best interests of humanity" (Quigley 1981: 33).

Milner Takes Charge

When Rhodes died in 1902, the leadership of the society passed largely to Milner, who shared the same goal as Rhodes of creating a truly global empire, which would be brought about by "secret political and economic influence behind the scenes and by control of journalistic, educational and propaganda agencies" (Quigley 1981: 49). Until his death in 1925, Milner greatly expanded the influence and aims of this society, in part through the creation of another group, which was known as the Milner Group, or Milner's Kindergarten.

This group was created during Milner's extensive time in South Africa where he held numerous positions, including serving as the High Commissioner for Southern Africa between 1897 and 1901, with the group comprised of capable officers who served as assistants and colleagues during this period. In fact, Milner played a core role in South Africa for years, including being one of the British officials who tried to cover-up the horrors of concentration camps used by the British during the Second Boer War. Between June 1901 and May 1902, approximately 28,000 people died, 22,000 of which were children, in British concentration camps in Southern Africa, and Milner was brought in to try and clean the mess up, resulting in him trying to find ways to spin the disaster to make it more palatable to the British public back home.

The Round Table Network

The creation of the Milner group was informed by three older groups that represented some of the most powerful networks at the heart of the British Empire (Quigley 1981: 6). The first was known as the Toynbee Group, which was formed in 1873 at Balliol College and dominated by Milner and the notable historian, Arnold Toynbee. The second group was known as the Cecil Bloc, created by the three-time British Prime Minister, Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, which represented political and social power (Quigley 1981: 6, 15). The third was the Rhodes secret society (Quigley 1981: 6). Over the coming years, prominent members of the Milner group created a network of "semi-secret discussion and lobbying groups" in various countries around the world, known as the Round Table Groups (Quigley 1966: 950). By 1915, there were Round Table Groups in seven countries, including in England, Canada, India, South Africa and New Zealand (Quigley 1966: 950).

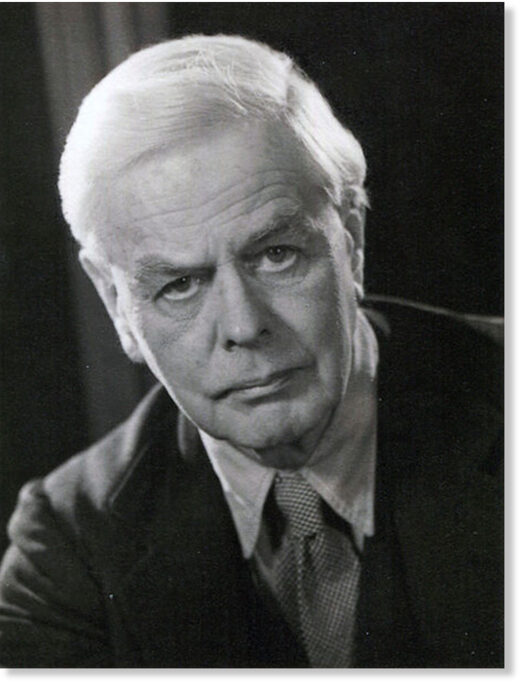

One of the most notable members of the Round Table network was Lionel Curtis (image on the right), an influential British official and author. Curtis was one of the strongest advocates of the British Empire morphing into a Commonwealth of Nations, and he supported the unification of Europe and the eventual establishment of a form of world government. During this period, the idea of a British-centric Empire ruling the world morphed into the idea of a multinational federation controlling the world. Importantly, Curtis also understood that "bankers and men who trade with countries abroad" have tremendous political value.

Chatham House Founded

Then, in a May 1919 meeting at the Hotel Majestic during Paris Peace Conference following the First World War, the members of the British delegation - who were largely members of the Milner Group (including Curtis) and the Cecil Bloc - agreed to form the British Institute of International Affairs, also referred to as Chatham House, which later became the Royal Institute of International Affairs, after the Institute was given a Royal Charter by King George V in 1926 (Quigley 1981: 182-184). A few years later, a parallel organization to Chatham House was founded in New York ,known as the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). The CFR grew out of the think tank called 'The Inquiry' that prepared President Woodrow Wilson for the Paris Peace Conference, with the CFR having close ties to the banking powerhouse, J.P. Morgan and Company (Quigley 1981: 190-191).

In the years after their formations, both organizations went on to attract many more prominent people, including national leaders, with members of Chatham House also being key architects and supporters of the League of Nations and the United Nations (UN), two of the most prominent internationalist organizations ever founded. Additionally, Chatham House received financial support from notable American businessmen and corporations, including the oil magnate, John D. Rockefeller, and the Ford Motor Company (Quigley 1981: 190).

Importantly, one of the reasons why we know so much about the workings of this network that created both Chatham House and the CFR, is because Dr Carroll Quigley, a Professor of History at Georgetown University until his death in 1977, who also taught at Harvard and Princeton, "was permitted for two years, in the early 1960's, to examine its papers and secret records" (Quigley 1966: 950). Quigley went on to state that he had very little aversion to the aims of this network, with the main issue he had being that they wished to "remain unknown," as Quigley believed that the role of this network in history was "significant enough to be known" (Quigley 1966: 950).

Fast forward to the present day, and we still find these organizations inspired by Rhodes operating today. Chatham House positions itself as Britain's premier think-tank, and it is clear that it still holds tremendous power. The current corporate membership of Chatham House is truly staggering. Members include: the European Commission, BP, the British Ministry of Defence, Apple, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Royal Dutch Shell, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Barclays, the Bank of England, Lockheed Martin, the BBC, Vodaphone, the Guardian, the Telegraph Media Group, CBS News, the Open Society Foundations and many more. Chatham House also has over 550 donors, with donors from 2018-19 including: the World Health Organization; the Rockefeller Foundation; Bayer AG; De Beers Group Services UK Ltf; GlaxoSmithKline Services Unlimited; the European Climate Foundation; the Kuwait Petroleum Foundation; Microsoft Limited; NATO Defense College; Rolls-Royce plc; the UK Labour Party; Google; the Economist; the Scottish Government; and UNICEF.

Furthermore, Chatham House has many academic members, including the University of Notre Dame, the Department of International Relations at the London School of Economics, and the United Nations University MERIT, which is a joint research and training centre of the United Nations University and Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Numerous prominent figures in UK and world politics have given speeches at the Institute, including former British Prime Ministers, Sir John Major and Tony Blair, the famous British media presenter, Jon Snow, and the current British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, who gave a speech in 2016 when he was Britain's Foreign Secretary.

What is clear from these exhaustive lists is that Chatham House represents a synergy of power that far exceeds what Rhodes even envisaged. One of the saddest parts of this whole epic story, however, is that many of the people who are campaigning to remove Rhodes' statue from an Oxford College, have never heard of Chatham House, and certainly do not understand its history.

Sources

Chatham House, Current Corporate Members https://www.chathamhouse.org/membership/corporate-membership/corporate-list

Chatham House (5 Dec 2016) Boris Johnson on UK Foreign Policy in the Era of Brexit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JuZwjX5cMn0

Chatham House (22 Jan 2012) Jon Snow: Time to Rethink Iran https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTpLUSyUXcQ

Chatham House (29 June 2018) John C Whitehead Lecture 2018: In Defence of Globalizationhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2oaYmh6XLFo

Chatham House (29 May 2019) Centenary Conversation: Sir John Major https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1KjGrwDfZeQ

Chatham House, Our History https://www.chathamhouse.org/about/history

Curtis, L. (1928). A British Appraisal. News Bulletin (Institute of Pacific Relations), 14-16 https://bit.ly/2YmYb4g

Donors to Chatham House - https://www.chathamhouse.org/about/our-funding/donors-chatham-house

Grose, P. Continuing the Inquiry, The Council on Foreign Relations

https://www.cfr.org/book/continuing-inquiry

Harris, P. (9 Dec. 2001) 'Spin' on Boer atrocities, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/dec/09/paulharris.theobserver

Lavin, D. (1995; 2011) From Empire to International Commonwealth: A Biography of Lionel Curtis (London: Oxford Scholarship Online) -https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198126164.001.0001/acprof-9780198126164

May, A. (22 Sep. 2005) Milner's Kindergarten, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-93711

Nelson, S. C. (9 June 2020) Who Was Cecil Rhodes And Why Do Campaigners Want To Topple His Statue At Oxford University? Huffington Post - https://bit.ly/2ztUvFG

New York Times (5 Jan 1977) DR. CARROLL QUIGLEY [Obituary] https://www.nytimes.com/1977/01/05/archives/dr-carroll-quigley.html

Parkinson, J. (1 April, 2015) Why is Cecil Rhodes such a controversial figure? BBC News -https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-32131829

Quigley, C. (1981) The Anglo-American Establishment (San Pedro: GSG and Associates).

Quigley, C. (1966) Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in our Time (New York; London: The MacMillan Company; Collier- MacMillan Limited).

Rietzler, K. (20 May 2019) The Hotel Majestic and the Origins of Chatham House, Chatham House -https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/hotel-majestic-and-origins-chatham-house

Shore, M. (1979). Cecil Rhodes and the Ego Ideal. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 10(2), 249-265.

Featured image: Christopher Hilton / Statue of Cecil Rhodes, High Street frontage of Oriel College, Oxford / CC BY-SA 2.0

Chatham House over the Jubilee weekend https://bit.ly/2N5FCg0 Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licensehttps://bit.ly/3hB3YME

Lady Thatcher exiting Chatham House following a talk https://bit.ly/2YE17Kd Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license https://bit.ly/37Bch6p

Jon Snow, Broadcaster, Channel 4 News https://bit.ly/3d4rvCd Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license https://bit.ly/3fuH2g1

Rather than being torn down, he should be front and center, in museums, anywhere a statue has been erected, with a plaque below his name, listing all the atrocities he has committed against innocent peoples for self aggrandizement, weatlh and position because he wanted to belong to a group/society, that he would not have accesses to if not going along with a psycho pathological ideology.

These statues are a reminder to learn from the past, Don't go there! Like a red light, it failed at that time in history and will fail again in our lifetimes.

Nowadays, it's called well, take your pick from the post modern era, seems to me they just make up names to suit the flavor of the day, the amount of monies that self interested parties are willing to cough up, to destroy. Regardless of so called skin color, ethnic origins, or simply just being, simply put a human being, that wants nothing more than to give support, love and understanding through hard times, nd good times. In essence to be human. For god sake where will dehumanization end.

With a devastating shower of comets!

[Link] This has nothing to do with skin color, it is a musical rendition, the impact of the social and cultural impacts of how some of us less fortunate, regardless of all those name tags we like to give humanity, cluster us into groups. In the end, we all suffer, the suffering one one affects another.