"In cold environments, there is longer virus survival than warm ones," Hong Kong University pathology professor John Nicholls told AccuWeather exclusively.

Nicholls and colleagues from a team at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, previously produced a study, which was published in February and has yet to be peer-reviewed, noting the effect of heat. Their research is based on one of the world's first lab-grown copies of SARS-CoV-2.

"Temperature could significantly change COVID-19 transmission," the authors note in the study. They also pointed out that the "virus is highly sensitive to high temperature."

On March 11, the World Health Organization officially declared the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic. This is the first pandemic in 11 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

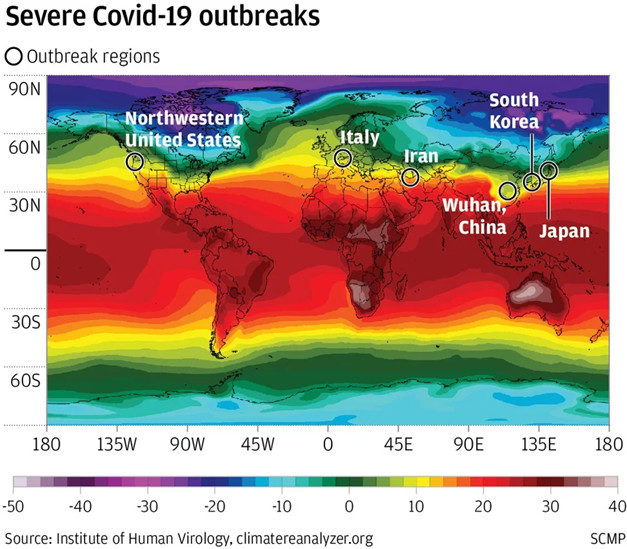

One recent research paper supported this assertion by pointing out the proximity of the major hotspots. The authors of the study, which was published last week, wrote that COVID-19 "has established significant community spread in cities and regions only along a narrow east-west distribution roughly along the 30-50 North latitude corridor at consistently similar weather patterns (5-11 degrees C [41 to 51 F] and 47-79 percent humidity)."

Some have suggested the possibility that weather factors might affect the virus - particularly the intensity and amount of hours of sunshine as well as heat and humidity. "Obviously, the virus is something we've never dealt with before, but if we look at other viruses ... they all had their peak during the cold season," said AccuWeather Founder and CEO Dr. Joel N. Myers.

"The statistics all show that they breed and survive longer when it's cold and dry," Myers said. "So, when it's warmer and more humid and there's a lot of sunshine, the statistics on all of the others show a virus is less lethal, it spreads less efficiently and less effectively among humans."

Dr. Joseph Fair, a virologist, epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist, suggested sunshine is a critical factor in subduing the virus.

"It really doesn't have anything to do with the warmth, but it has to do with the length of the day and the exposure to sunlight, which inactivates the virus through UV light," Fair, who is an MSNBC science contributor, said during an appearance on the network. "We expect a dip in infections as we would see with the cold and flu in the spring and summer months.

But, he cautioned, "The science is still out. We can assume this will follow typical other coronavirus cases. We can expect a dip in the summer. But that doesn't mean that we will be out of the woods ... Everyone in the scientific and public health community expects it to be back in the fall and we expect to be in this for quite some time."

There is a range of opinions on the matter in the infectious disease community. Some infectious disease experts have warned that unlike cases of seasonal flu, which tend to decline in the spring and summer months, SARS-CoV-2 will not behave in the same manner.

Marc Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology at Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health, recently posted an analysis in which he said that warmer weather will "probably not" significantly slow the spread of the disease.

One thing the infectious disease experts are all unable to evaluate: "Once the virus leaves the body, human factors are more unpredictable," Nicholls told AccuWeather.

Those variables could include people going to work with symptoms rather than staying home, the inability of countries or regions to have effective screening tests or isolation facilities, or health care workers not having access to personal protective equipment because of supply shortages, among other possibilities.

"We could call these the 'bozo factors,'" Nicholls said. Those types of unpredictable, unmeasurable variables would mean "all bets are off as to whether the hoped-for decrease in summer will eventuate."

Additional reporting by Jesse Ferrell.

Reader Comments

that is the game in a nutshell.

i always thought that the govt. was watching the techniques of the real good players.

so if you had a bacteria, virus, or parasite that hid it's symptoms for a while you would always crush the game as you could infect half the world before anyone really discovered it was a true pandemic.