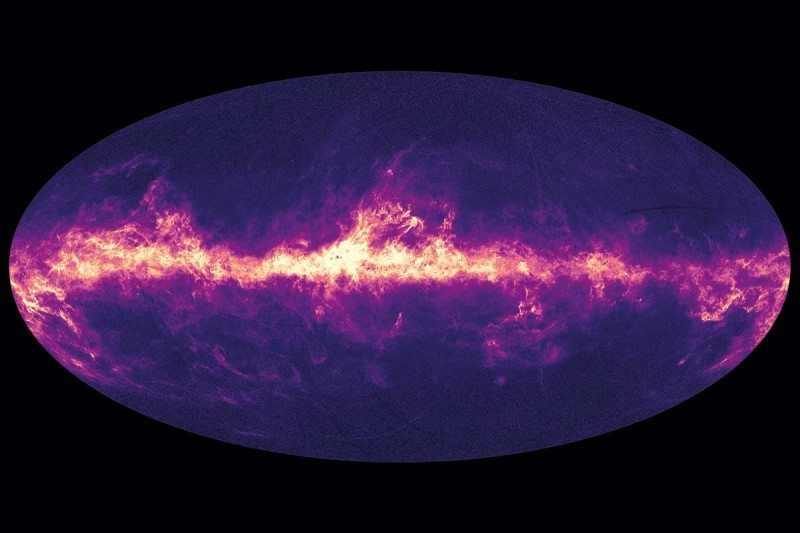

© ESA/Gaia/DPACLight from 87 million stars shines through dust in our galaxy’s disc

The universe just got even more confusing. Last week, the biggest ever 3D map of our galaxy was released as part of the second batch of data from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite. The long-awaited measurements revealed the location and brightness of 1.7 billion stars in the Milky Way.

But the first analysis of the data has also crystallised our confusion about the rate of the universe's expansion. We have two ways to determine this rate, expressed in a quantity called the Hubble constant,

and they have always come up with different values. Some researchers had hoped that the Gaia data released on 25 April might lessen the divergence, but it has only got worse.

One determination of the Hubble constant comes from the cosmic microwave background (CMB), a relic of the first light in the cosmos after the big bang. Researchers have used the now defunct Planck space observatory to examine this light and figure out how fast the universe was expanding back then. Those values can then be plugged into models of cosmic evolution to predict how fast the universe should be expanding today.

The other method involves directly measuring the distances to stars called Cepheid variables. This lets us figure out how quickly objects in the local universe are moving away from us.

The technique gives a Hubble constant more than 9 per cent larger than with the CMB method.In the past, we have only been able to measure a few Cepheids at a time, but Gaia pinpointed 50 of them. Adam Riess at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues analysed Gaia's Cepheid data to see whether the Hubble constant discrepancy would alter or vanish altogether.

"Not only is it confirmed, but it's actually reinforced," Riess says. Prior to this analysis, he says, there was a 1 in 1000 chance that the apparent discrepancy was just a fluke - now, that has fallen to only 1 in 7000.

If the discrepancy is real, it means that something is wrong with our models of the universe's evolution. And it's looking more and more real.

Undetected particles out there could be undermining our models, or maybe our guesses about the nature of dark matter and dark energy are wrong, says Reiss. "When we say the Hubble constant should be lower, that's with models using the most vanilla, least interesting versions of dark matter and dark energy," he says.

"But maybe there's a wrinkle. Maybe it's much weirder."Over 22 months, Gaia classified and measured the brightness of 500,000 standard candles - variable stars that can be used to measure distances to other astrophysical objects. The satellite also mapped the positions of 14,099 objects within our own solar system - mostly asteroids - as well as half a million distant galaxies and 12 dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way.

Closer to home, the Gaia data revealed a disturbance in our galaxy.

The satellite galaxies that revolve around the Milky Way are gravitationally bound to it, so astronomers agree it is likely that some interacted with our galaxy in the past, perhaps smashing through its disc.Thanks to Gaia, we now have evidence that another galaxy perturbed the Milky Way's disc relatively recently.Teresa Antoja at the University of Barcelona in Spain and her colleagues analysed the motions of more than 6 million stars from the Gaia data set, and found patterns never seen before. Plots of these stars' velocities have swoops, arches and spirals, indicating patches of stars that are moving together (

arxiv.org/abs/1804.10196).

If the Milky Way were in equilibrium and hadn't been recently perturbed, those patterns would not appear.

Their presence indicates that something has shaken up the stars recently enough that their orbits have yet to relax back to a stable state.The researchers found that the Milky Way was probably perturbed between 300 and 900 million years ago, which is also the last time an object called the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy is thought to have made a close pass.

"This is just the beginning for Gaia," says Riess. "Gaia should be delivering data that's five or six times more precise than this in a few years." And for now, analysis of the deluge of data we have just received is nowhere near complete.

This article appeared in print under the headline "Star map adds to cosmic confusion"

Of course they're erroneous. Quite a number of people have been trying to tell these nutcases this for decades. It started with Jan Oort's dilemma--trying to reconcile distance by triangulation with redshift and the cockamamie notion the universe, along with space is growing. And then resorting to that ridiculous idea that there is dark matter and dark energy out there that can't be detected to explain the discrepancy.

The universe is not expanding, redshift is not a valid technique for measuring distance, and there are errors in the measurement of the CMB, all of which negates their being able to confirm their erroneous hypothesis.

Gaia is a waste of research funds because we've already known the answers--they just don't want to admit their models have been crap for nearly a century.