Ever since The New York Times opened the floodgates last October with its report about producer Harvey Weinstein's atrocious history of sexual harassment, there has been a torrent of accusations, ranging from the trivial to the criminal, against powerful men in all walks of life.

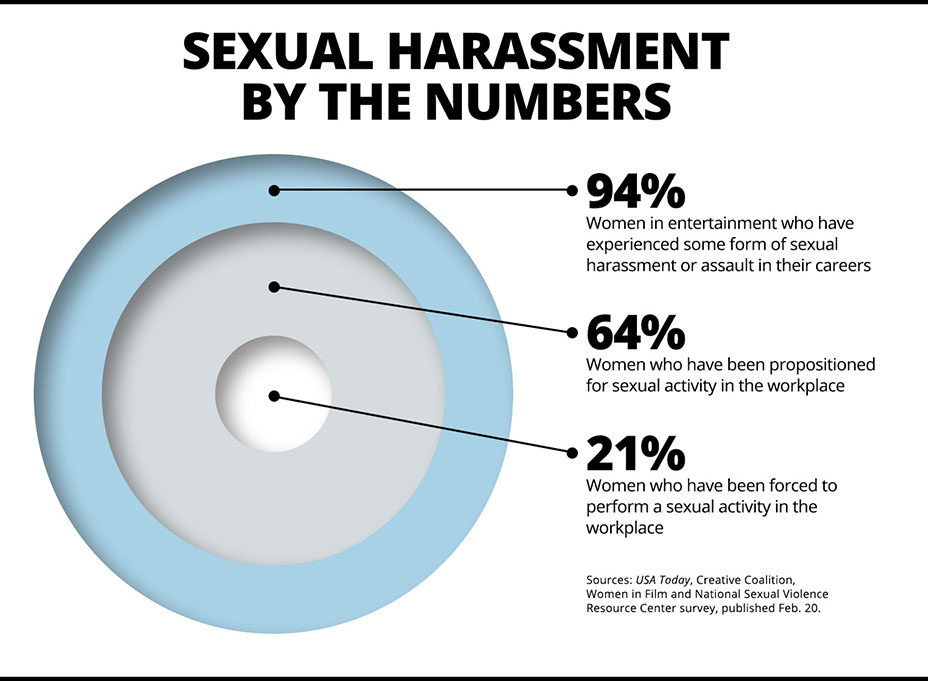

But no profession has been more shockingly exposed and damaged than the entertainment industry, which has posed for so long as a bastion of enlightened liberalism. Despite years of pious lip service to feminism at award shows, the fabled "casting couch" of studio-era Hollywood clearly remains stubbornly in place.

The big question is whether the present wave of revelations, often consisting of unsubstantiated allegations from decades ago, will aid women's ambitions in the long run or whether it is already creating further problems by reviving ancient stereotypes of women as hysterical, volatile and vindictive.

My philosophy of equity feminism demands removal of all barriers to women's advancement in the political and professional realms. However, I oppose special protections for women in the workplace. Treating women as more vulnerable, virtuous or credible than men is reactionary, regressive and ultimately counterproductive.

Complaints to the Human Resources department after the fact are no substitute for women themselves drawing the line against offensive behavior - on the spot and in the moment. Working-class women are often so dependent on their jobs that they cannot fight back, but there is no excuse for well-educated, middle-class women to elevate career advantage or fear of social embarrassment over their own dignity and self-respect as human beings. Speak up now, or shut up later! Modern democracy is predicated on principles of due process and the presumption of innocence.

The performing arts may be inherently susceptible to sexual tensions and trespasses. During the months of preparation for stage or movie productions, day and night blur, as individuals must melt into an ensemble, a foster family that will disperse as quickly as it cohered. Like athletes, performers are body-focused, keyed to fine-tuning of muscle reflexes and sensory awareness. But unlike athletes, performers must explore and channel emotions of explosive intensity. To impose rigid sex codes devised for the genteel bourgeois office on the dynamic performing arts will inevitably limit rapport, spontaneity, improvisation and perhaps creativity itself.

Similarly, ethical values and guidelines that should structure the social realm of business and politics do not automatically transfer to art, which occupies the contemplative realm shared by philosophy and religion. Great art has often been made by bad people. So what? Expecting the artist to be a good person was a sentimental canard of Victorian moralism, rejected by the "art for art's sake" movement led by Charles Baudelaire and Oscar Wilde. Indeed, as I demonstrated in my first book, Sexual Personae, the impulse or compulsion toward art making is often grounded in ruthless aggression and combat - which is partly why there have been so few great women artists.

Take director Roman Polanski, for example, whose private life has evidently been squalid and contemptible. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, founded as a guardian of industry reputation in 1927, would be perfectly justified in expelling him. But no sin or crime by Polanski the man will ever reduce the towering achievement of Polanski the artist, from his starkly low-budget Knife in the Water (the first foreign film I saw in college) through masterworks like Repulsion, Rosemary's Baby and Chinatown.

The case of Woody Allen, who began his career as a comedy writer and stand-up comedian, is quite different. Polanski's chilly worldview descends from European avant-garde movements like surrealism and existentialism. In a sinister cameo in Chinatown, Polanski sliced open Jack Nicholson's nose with a switchblade knife. Allen, however, in his onscreen persona of lovable nebbish, seductively ingratiated himself with audiences. Hence the current wave of disillusion with Allen and his many fine films emanates from a sense of deception and betrayal, including among some actors who once felt honored to work with him.

It was overwhelmingly men who created the machines and ultra-efficient systems of the industrial revolution, which in turn emancipated women. For the first time in history, women have gained economic independence and no longer must depend on fathers or husbands for survival. But many women seem surprised and unnerved by the competitive, pitiless forces that drive the modern professions, which were shaped by entrepreneurial male bonding. It remains to be seen whether those deep patterns of mutually bruising male teamwork, which may date from the Stone Age, can be altered to accommodate female sensitivities without reducing productivity and progress.

Women's discontent and confusion are being worsened by the postmodernist rhetoric of academe, which asserts that gender is a social construct and that biological sex differences don't exist or don't matter. Speaking from my lifelong transgender perspective, I find such claims absurd. That most men and women on the planet experience and process sexuality differently, in both mind and body, is blatantly obvious to any sensible person.

The modern sexual revolution began in the Jazz Age of the 1920s, when African-American dance liberated the body and when scandalous Hollywood movies glorified illicit romance. For all its idealistic good intentions, today's #MeToo movement, with its indiscriminate catalog of victims, is taking us back to the Victorian archetypes of early silent film, where mustache-twirling villains tied damsels in distress to railroad tracks.

A Catholic backlash to Norma Shearer's free love frolics and Mae West's wicked double entendres finally forced strict compliance with the infamous studio production code in 1934. But ironically, those censorious rules launched Hollywood's supreme era, when sex had to be conveyed by suggestion and innuendo, swept by thrilling surges of romantic music.

The witty, stylish, emancipated women of 1930s and '40s movies liked and admired men and did not denigrate them. Carole Lombard, Myrna Loy, Lena Horne, Rosalind Russell and Ingrid Bergman had it all together onscreen in ways that make today's sermonizing women stars seem taut and strident. In the 1950s and '60s, austere European art films attained a stunning sexual sophistication via magnetic stars like Jeanne Moreau, Delphine Seyrig and Catherine Deneuve.

The movies have always shown how elemental passions boil beneath the thin veneer of civilization. By their power of intimate close-up, movies reveal the subtleties of facial expression and the ambiguities of mood and motivation that inform the alluring rituals of sexual attraction.

But movies are receding. Many young people, locked to their miniaturized cellphones, no longer value patient scrutiny of a colossal projected image. Furthermore, as texting has become the default discourse for an entire generation, the ability to read real-life facial expressions and body language is alarmingly atrophying.

Endless sexual miscommunication and bitter rancor lie ahead. But thanks to the miracle of technology, most of the great movies of Hollywood history are now easily accessible - a collective epic of complex emotion that once magnificently captured the magic and mystique of sex.

Women (and men) can only advance by embracing the technology that made them what they are today (and what will make them tomorrow).

This technology is pure and unadulterated (I think).

It will lead to better romance (I think).

The ancient stereotypes must be replaced by the modern stereotypes.

Because these stereotypes are very much better (I think).

signed,

I AM WOMAN (I THINK)

(sarcasm)