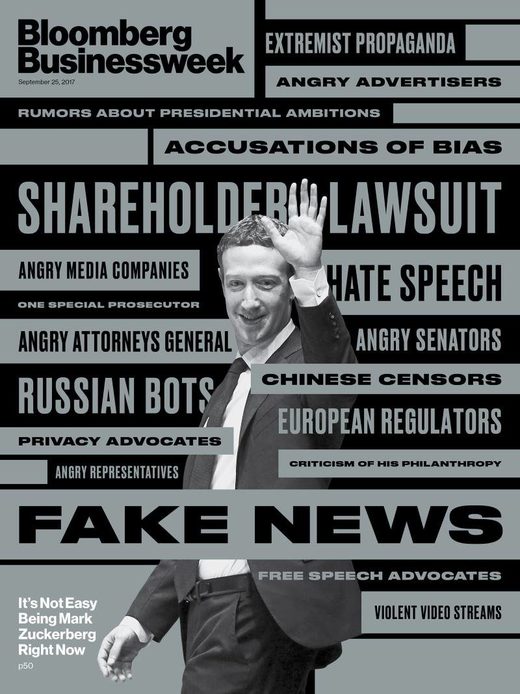

© El Comercio/GDA/Zuma Press/Bloomberg BusinessweekMark Zuckerberg

Technically speaking, Mark Zuckerberg has been on paternity leave. In late August his wife, Priscilla Chan, gave birth to their second child, a girl. But though Zuckerberg, the chief executive officer of

Facebook Inc., stayed away from the office for a month after the delivery, he has been utterly unable to avoid what's become a second full-time job: managing an escalating series of political crises.

In early September, Facebook disclosed that it sold $100,000 in political ads during the 2016 election to buyers who it later learned were

connected to the Russian government. Richard Burr of North Carolina and Mark Warner of Virginia, the most senior Republican and Democratic members of the Senate Intelligence Committee, have said they're

considering holding a hearing, in which case Zuckerberg could be asked to testify.

Meanwhile, special counsel Robert Mueller has made Facebook a focus of his investigation into collusion between the Russian government and Donald Trump's campaign. A company official says it's "in regular contact with members and staff on the Hill" and has "had numerous meetings over the course of many months" with Warner. On Sept. 21, Zuckerberg said the company

would turn over the ads to Congress and would do more to limit interference in elections in the future. Facebook acknowledges that it has already turned over records to Mueller, which suggests, first, that the special counsel had a search warrant and, second, that Mueller believes something criminal happened on Zuckerberg's platform.

The Russia investigations complicate Zuckerberg's efforts to shore up support for Facebook in the wake of a bitter election. Even as the company enjoys

record profitability-its market value has more than doubled since 2015, to $500 billion, making Zuckerberg the

world's fifth-richest person-Facebook faces criticism for its role in distributing pro-Trump propaganda during the 2016 election (one viral story falsely claimed that the pope had endorsed Trump) and for contributing to a climate of extreme polarization. On Sept. 14,

ProPublica reported that it had managed to purchase ads targeted at users who'd listed interests such as "Jew hater" and "How to burn Jews."

Facebook

quickly changed its ad system to prevent similar purchases, but the episode gives further ammunition to critics who worry that the company has grown too powerful with too little oversight. Abroad, Facebook faces challenges from aggressive European

antitrust regulators and governments suspicious of both its

power and its treatment of user data. The idea of a crackdown is catching on in the U.S., too, amid a larger backlash against Silicon Valley. Zuckerberg has become a big, enticing target for both liberal Democrats, who see him as a media-devouring monopolist, and for nationalist Republicans, who see an opportunity to rail against the company that embodies globalization more than any other.

Since January, Zuckerberg has been on a tour of America that seems designed to combat those perceptions. He's done laps at a Nascar track in North Carolina, sat in a big rig at a truck stop in Iowa, and jawed with workers at a fracking site in North Dakota. The ongoing road trip, organized in part by David Plouffe, Barack Obama's former campaign manager and the head of policy and advocacy at

Zuckerberg's philanthropic organization, is being documented by a former presidential photographer for

Newsweek. Much of the time on these trips, he's accompanied by private security guards who resemble Secret Service agents.

The optics of these moves, and the people Zuckerberg has hired to orchestrate them, have caused many to suspect that he might be doing more than burnishing his image. In addition to Plouffe, Zuckerberg has hired several former senior Obama White House officials and Hillary Clinton's pollster. In the past year he's delivered a kind of proto-stump speech at Harvard and disclosed that he's no longer an atheist. "Now I believe religion is very important," he wrote on Facebook last December. Most tellingly, for some anyway, in late 2015 he moved to change Facebook's corporate charter to allow him to maintain control in the event-totally hypothetical, of course-he were to run for office. (The move was the subject of a class-action lawsuit.)

Since his paternity leave began, Zuckerberg has also raised funds for victims of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, announced

a $75 million investment in a new global health initiative, and led a

campaign to protect the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, the Obama initiative allowing young undocumented immigrants, or Dreamers, to remain in the U.S. Zuckerberg's political engagement has been so extreme that one night in August, presumably while the baby slept, he

argued with anti-immigrant trolls for several hours on Facebook.

The most popular explanation for all this politicking, one shared by some members of the Trump administration, is that Zuckerberg is exploring whether to seek the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, when he'll be 36 years old. "He would be formidable if he ran," says Alex Conant, a Republican political strategist who previously served as communications director for Florida Senator Marco Rubio's presidential campaign. "It's as if, 50 years ago, the publisher of the

New York Times ran for president. Except that Facebook is even more powerful than the

Times ever was." A

survey conducted in July by Public Policy Polling found Zuckerberg running even with Trump in a hypothetical race.

Mark Zuckerberg Is Not Running for PresidentZuckerberg denies he's running and seems irritated by the speculation. But he concedes that many of the things he's done might seem political-at least from a certain cynical vantage point that he, for one, doesn't share.

"I get what people are saying," he says in an interview at Facebook's headquarters in Menlo Park, Calif., on a warm afternoon in June. Zuckerberg has made himself available to discuss Facebook's efforts-and his own-to make the world a better place. During the interview he insists his travels have been about personal discovery, not politics. Zuckerberg is a relentless self-improver who undertakes an annual personal challenge. One year he learned Mandarin; another year he built his own artificial intelligence bot, getting Morgan Freeman to provide the voice. This year was about getting in good with the flyover states. "Wouldn't it be better," he asks with a sly smile, "if it was actually an accepted thing for people to want to go understand how other people were living?"

Of course, the Zuckerberg tour, which will hit six more states between now and Thanksgiving, isn't just about understanding. It's also an attempt to cast Facebook's founder as someone other than an aloof operator who doesn't care whether you use the platform to share pictures of your grandkids or advertise to aspiring Jew-burners. Zuckerberg wants America to understand him and, in doing so, understand Facebook. As he puts it: "People trust people, not institutions." It's a nice thought, but it remains to be seen whether Zuckerberg, whose communication skills aren't as sharp as his competitive instincts, can pull it off. He's been underestimated before-by Harvard, by competitors, and by Wall Street-but he's never faced the mix of outcry and scrutiny he's up against today. Washington has Facebook in its sights.

Read the rest

here.

This without a shadow of a doubt means that the supposedly Russian linked ads had NO effect on the election, although AIPAC meddling interferes with every single federal election cycle.