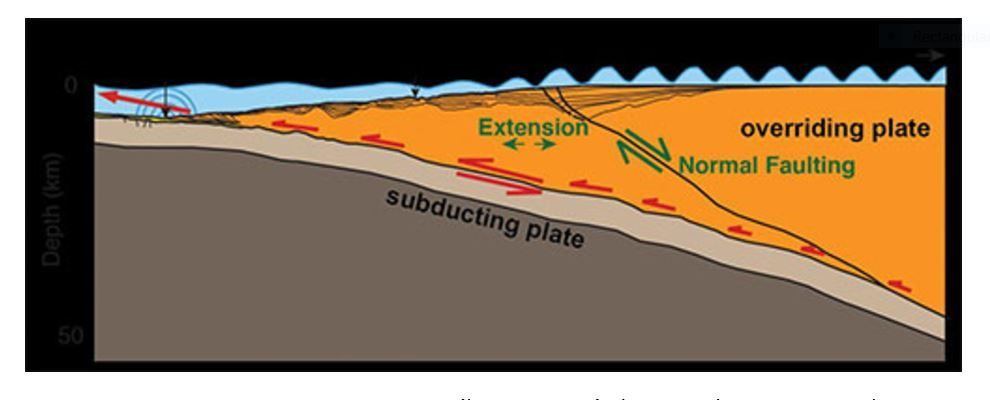

Major tsunamis usually occur at the shallow portions of subduction zones, the areas where one of the tectonic plates that make up Earth's surface dives below another. Called crash zones, they are dangerously active and tectonic interactions can cause some of the world's biggest earthquakes and tsunamis.

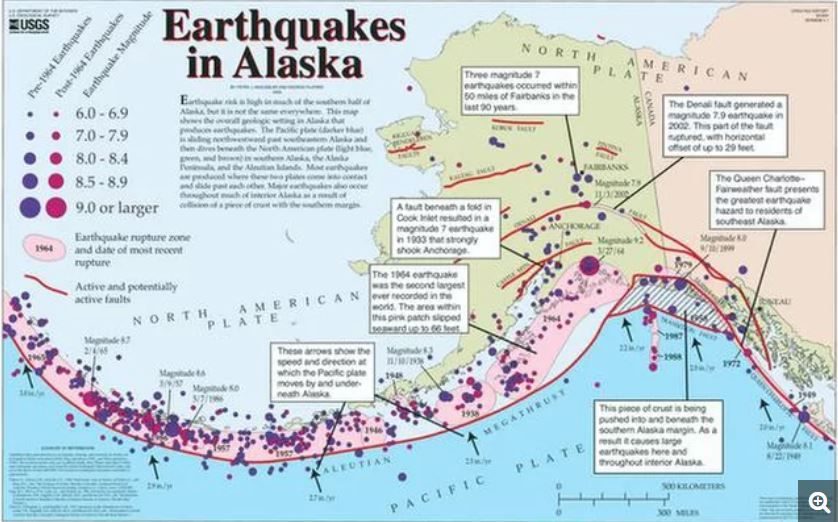

The research, led by seismologist Anne Bécel of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, shows that segments of subduction zones capable of producing tsunamis have three characteristic structural configurations and the mapping and study of the subduction zone off the Alaska coast "suggests this part of Alaska is particularly prone to tsunami generation."

"The possibility that such features are widespread is of global significance." In addition to Alaska, she said, "waves could hit more southerly North American coasts, Hawaii and other parts of the Pacific." Bécel noted that when the energy at the point of subduction is high and suddenly is released, the resulting earthquake can make the ocean floor jump up and down like a spring. The motion then transfers to the overlying water, creating the tidal wave.

Three key structural configurations in Alaska subduction zone

The first key feature the Alaskan zone has in common with tsunami-prone subduction zones is seen at the boundary where the tectonic plates meet. Using seismic reflection imaging, the research team surveyed the 120-mile-wide (200 kilometers) Shumagin seismic gap in the Alaska Peninsula that stretches southwest from mainland Alaska.

The boundary where the two tectonic plates meet is rough, rather than smooth. This feature keeps the two plates from slipping easily past one another, resulting in a build-up of energy. When that energy level reaches a certain point, it is released and can trigger a major earthquake and possibly, a tsunami, according to the researchers.

A third feature that is very similar to the fault that caused the 2011 Tokohu earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan is series of cracks originating in the plate boundary. The team found a cluster of seismicity (small earthquakes,) that indicate the fault is active. The pattern of the cluster of earthquakes suggests the frictional properties on the seaward side of the fault differ from those on the landward side.

Coauthor, Donna Shillington, a Lamont-Doherty seismologist, says this finding suggests it could be dangerous. "With that big fault there, that outer part of the plate could move independently and make a tsunami a lot more effective," said Shillington. "You get a lot more vertical motion if the part that moves is close to the seafloor surface."

Other coauthors on the research team included Spahr Webb, Mladen Nedimovic and Jiyao Li of Lamont-Doherty; Matthias Delecluse and Pierre-Henri Roche of France's PSL Research University; Geoffrey Abers and Katie Keranen of Cornell University; Demian Saffer of Penn State; and Harold Kuehn of Canada's Dalhousie University.

This very interesting study, entitled, "Tsunamigenic structures in a creeping section of the Alaska subduction zone," was published in the online journal Nature Geoscience on July 24, 2017.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter