So Jessica packed her bag and followed the pied piper out of town. Shortly after giving birth to their first son, Jessica and her older suitor arrived in New York City with plans to get married and start a new life together. Or so she thought. That's when Jessica's American Dream went horribly sideways.

The man quickly became physically and emotionally abusive, Jessica would later tell counselors. He isolated her from everyone else and forced her to start working seven days a week in cantina bars that doubled as brothels.

Jessica, whose last name has been withheld to protect her identity, didn't realize it at first, but her "courtship" had really been a targeted recruitment by a skilled sex-trafficker. The headhunter had not come to town looking for a wife, rather a victim for the skin trade. And like most so-called padrotes, or Lothario-type recruiters who lure small-town teens into trafficking situations with false promises of romance, work and money, he was playing the long game.

Trafficking experts say it's not uncommon for recruiters to invest years identifying, coaxing, extracting then enslaving their victims in U.S. trafficking syndicates before returning to Mexico or Central America to find new prey. Most of the victims are girls, and most are targeted when they are still young teens. Some are brought to the U.S. right away, while others are groomed until they 18 to avoid raising any red flags from traveling with a minor.

That was the case with Jessica, who remained trapped as a sex slave in New York for 10 years until a police raid freed her and brought her to Sanar's office for post-traumatic counseling.

Jessica worked with healing professionals to understand her trauma and slowly put her life back together. Today Jessica, who was smuggled into the country a decade ago but has since been able to get a work permit and a T-Visa, has a full-time job, is taking English classes and continues to participate in expressive arts groups at Sanar.

"Sometimes I have negative thoughts and I think about what I have worked on in counseling and it helps," Jessica told Sanar staff members in a quote provided to Fusion.

Jessica's story is tragic, but shockingly common. She is one of the untold thousands of young women stuck in similar situations across the United States. Some manage to get free, or reach out for help, but it's unknown how many women remain in bondage.

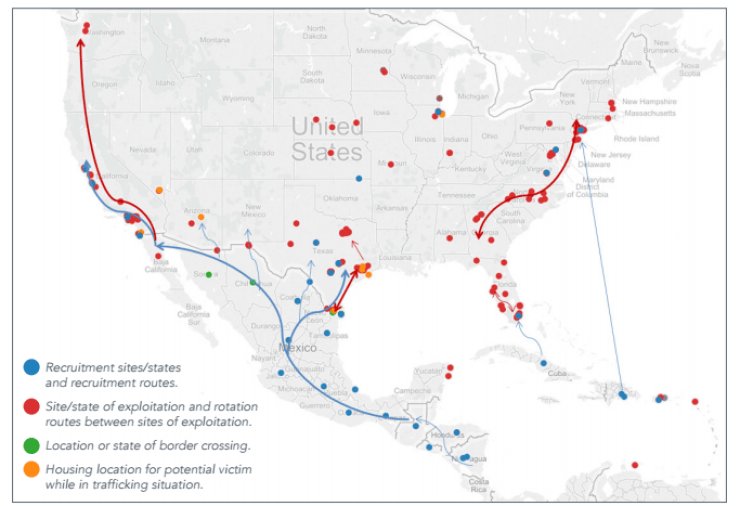

A new report published today by Polaris, a global leader in the fight to end modern slavery, identified 1,300 potential sex-trafficking victims from Latin America who were forced to work in cantina-like brothels in 20 U.S. states and Puerto Rico over the past nine years. But that's just the number of women who reached out for help on the National Human Trafficking Hotline or the Befree Textline. Sadly, that only represents the tip of a massive underground network that appears to be based in New York and has tendrils that reach throughout the country and hemisphere.

Sex-trafficking operates in a closed network, but oftentimes in plain sight. To the unacquainted, it's easy to see without recognizing. Men who hand out "tarjetas de viejas" —or "chick cards"— on the street corners in New York, cantinas that charge excessively high prices for drinks, and D.C. cabbies who ask single men if they're looking for action can oftentimes be signs of a trafficking network lurking just below the surface, experts say.Key findings about trafficking victims:Key findings about traffickers:

- 96% of were female

- 63% were minors

- 72% were Latina, mostly from Mexico, Brazil and Central America

- 34% were smuggled across the border, but some reportedly didn't realize they had entered the U.S. illegally.

- At least 29% came to the U.S. chasing fake job offers.

- 62% say there were confined or physically isolated in the U.S.

- 51% report economic abuse, including wage theft or imposition of un-payable debts

source: More than Drinks for Sale: Exposing Sex Trafficking in Cantinas and Bars

- 70% were Latinos

- at least 35% had U.S. citizenship

- 67% of traffickers were men, nearly one-third were women.

Commercial sexual exploitation is so pervasive across the United States that a heat map of reported sex-trafficking cases looks like the coverage network of a tertiary cellphone provider. But because sex-trafficking is so prevalent, it's the dark spaces on the map that experts find the most worrying because it suggests those are the areas where awareness and law enforcement are the weakest.

"Every day in the U.S. young women and girls are held prisoner by criminal networks that sell sex in cantinas and bars right in our backyards," says Bradley Myles, CEO of Polaris.

Cantinas and bars are only part of the equation, however. Sex trafficking has also gone mobile, with women delivered to homes or motels while the drivers wait outside. But by focusing on cantinas and bars—establishments that are more likely to be visited by law enforcement—Polaris is hoping to work with authorities to better identify trafficking and deal with it when they find it.

"We work on training law enforcement on how to do assessment for trafficking and how to approach the victims in a culturally competent manner," says My Lo Cook, director of Polaris' Strategic Initiative in Mexico.

It's a tricky task. Many of the victims don't speak English, and some only speak an indigenous dialect. Many of the women are mistrustful of authorities, especially since police have been known to misdiagnose them as sex workers instead of sex slaves. And some women are so entangled in a web of lies, psychological manipulation, or traumatic disassociation that they don't even realize they're victims. Other victims are aware of what's going on, but are too afraid or ashamed to find help. Still others who were smuggled into the country don't realize they have legal rights in the U.S.

And then there are women who have been exposed to so much violence in their lives that their ability to even identify victimization and abuse becomes totally warped by a life of unspeakable horrors. That's particularly true for women from places like El Salvador, where many victims of sex trafficking were initiated into an awful culture of gang rape and violence before being trafficked to the U.S.

"We have seen a huge spike in women from El Salvador who are coming over, particularly from families that have been impacted by MS-13 violence, and people connected with MS-13 are also doing the trafficking," Sanar's Keisel told me. "It's incredible violence that we have not seen before. Family members who are dismembered...The threat to safety and security is so real that sometimes it's even difficult to do some of the trauma-processing work."

The challenges facing police and victim-response agencies are daunting and ever-changing in a world where criminal syndicates are oftentimes a few steps ahead of the law. It's even more complicated in an election year, when any attempt to have a serious national dialogue about such complicated issues immediately gets shouted down by fear-mongering, rabble-rousing, bottom-fishing candidates.

But activists say there's never a better time than now to start facing the harsh reality of sex-trafficking. It's not a problem that society can afford to ignore any longer.

"We have to put this issue on the radar, because if you don't look for it, you don't see it," Polaris' Cook says.

For more on sex trafficking, see Fusion's special investigation Pimp City.

Reader Comments

I was a sex slave for wanna-be Hollywood Starlets! (Snif..) I'll never get over it...

WHAT - EVER.

R.C.

To Clarify-before I get too much grief,

Articles like this are part and parcel of the overriding agenda (MSM for the PTB) to erase local government control, and the US Constitution's logical presumption of the right to govern NOT from God to the King and then down, but instead by PERMISSION AND AGREEMENT of the governed.

We are witnessing a multi fronted attack on the rights of individuals vis a vis the state. This is simply the latest version of the proclaimed drug war and unproclaimed war on privacy/ the right of the individual to be left alone.

Why is it that every time something bad happens (which is ALWAYS against laws firmly established in place - e.g., rape, murder, etc.) that we hear screaming for yet new laws - as though the crimes referenced were not clearly sufficientl to put away the scumbags for life?

Why the need for ever more laws, every one of which takes a little bit more from the freedom of the individual, which is promptly swallowed by the government/state, which then expands on THAT! (E.g., PatrioSh*t act. ('PS Act') Built as a temporary law with a sunset provision. I do not believe any sunset provision law/agency has EVER not come up with ongoing reasons for its continuing existence just like the PS Act, now renewed - despite proclaimed 'liberal' (sic) opposition - I forget how many times.

THAT IS THE NATURE OF ALL HUMAN ORGANIZATIONS/ENTITIES. They take on lives of their own and find (or create) a reason(s) for their continuing 'need' to - be a leech on - the public.

I long ago learned a wise expression about the law: 'Hard cases make bad law.'

That IS the truth.

R.C.

Yes RC... i fully agree fully with you, as usual.

Nice to be back to normal

I so like that song.... i ll bet you a french- canadian quarter that you will listen to it.

Nice to see you've found a creative outlet for your steam. You re a quick learner and humble. Great traits ... imho ;-)