The remains of the 16-18 year old girl is the pride of the National Museum of Denmark. Whilst skin and body parts have disappeared over the years, the young girl's unique style of dress is exactly as it was when she was buried about 3,400 years ago.

The Egtved Girl is, in other words, a Danish Bronze Age icon. Only now it turns out that she was not actually Danish.

This surprising discovery was made following new analyses of the Egtved girl's teeth. Further analyses of her clothes, hair, and nails, revealed that she had also travelled huge distances in the last 23 months of her life.

"It's as wild as it can be. We've never had an indication that she shouldn't be from the local area around Egtved, and when I started to investigate her clothes, it was to examine the contemporary trade patterns. We're all extremely surprised," says PhD Karin Margarita Frei, who is the senior researcher at the National Museum.

"In peoples' minds, the iconic Egtved girl is Danish -- now it turns out that in reality, she was a migrant," says Professor Helle Vandkilde, who was not involved in the new study herself. "That the girl was a traveller, and almost what we would today call a commuter, will surely have an impact on the direction of future research in the coming years."

The new study has been published in Nature Scientific Reports.

Egtved girl is more international than previously thought

The new discoveries were made possible by a method that Frei developed and uses strontium isotope analyses of textiles to reveal how people produced the raw materials.

The cutting-edge method is based on the radioactive trace element strontium, which is found in plants, soil, and water.

Animals and humans take up strontium from the food and drink they consume. A sheep grazing in a field in Denmark, Germany, or anywhere else, is actually eating grass with a specific strontium isotope values, characteristic of that particular place. By analysing the sheep's wool, it can indicate where in the world they were when they were munching away on the grass.

When Frei analysed the strontium isotopes in the wool of the Egtved girls' clothes, she was very surprised.

The clothes were made of wool from somewhere outside Denmark -- which is not what she had anticipated.

"She has this splendid dress that is what has made her so famous and well-known; but the wool did not come from sheep that grazed in Denmark. The raw material comes from several locations, and they're all outside Denmark," says Frei. "She is far more international than we thought."

Her teeth reveals that she was not a Dane

Strontium isotopes can also be analysed in bone samples. We all take up strontium throughout our lives, via the food and drink that we consume.

The Egtved Girl lived approximately 3,400 years ago in the Bronze Age.

While Egtved girl's bones no longer exist, her teeth can be analysed instead.

Maybe you do not think about it everyday, but your teeth are actually a kind of bone. They also take up strontium when you eat and can thus reveal where you ate. What's more, they can provide a precise timeline of where you were born and where you lived for most of your childhood.

This is because the tooth enamel (the outermost layer of teeth) develops at specific times in childhood.

The first molars are the first to finish forming tooth enamel which then remains unchanged into your adult life.

Strontium isotopes in teeth can in other words reveal where you spent your early childhood.

When Frei analysed Egtved girl's molar tooth she could clearly see that the Bronze Age girl had not grown up in Denmark.

(This does not mean that the Frei can say where Egtved girl grew up with 100 per cent certainty. But we will get to that later.)

Bright idea gave "phenomenal results"

If the Egtved Girl had been alive today, Frei would probably have had a few questions for her. Where did she come from? What was she doing in Denmark? Where did she go and why did she end up in a burial mound in Egtved?

Whilst she cannot ask the Egtved Girl herself, she was nonetheless inspired by the findings from the girl's dress, and it struck her that there may be another way to find the answers she was looking for.

"I realised that human hair kind of resembles sheep wool, and so I could apply the same method and develop it specificially for human hair," says Frei with enthusiasm.

After completing the strontium isotope analyses of her own hair, she could see that human hair reveals a person's whereabouts just like the sheep wool.

"Then I tried to do it on her hair too, and from it I could see that the results were phenomenal -- really incredible."

The girl's teeth had previously revealed she was between 16 and 18 years old when she died.Mapping the last 23 months of Egtved girl's life

At the girl's feet were the cremated remains of a 5-6 year old child, who had probably died some time earlier.

The child shares strontium isotope values with the girl and whilst nothing suggests that they have travelled together, they seem to have come from the same place.

Their relationship to each other is unknown since neither of them left any DNA for analysis.

Egtved girl's 23 centimetre long hair gave a unique insight into the last 23 months of her life -- and she was quite a traveller.

"She has travelled far and wide, back and forth -- it's unbelievable," says Frei.

Professor Kristian Kristiansen, who is co-author of the study and helped with the archaeological interpretations of the finds, suggests that Bronze Age people moved very far and very fast.

In 2012, he attempted to extract DNA from the Egtved girl's hair to find out where she had come from. This was in collaboration with Assistant Professor Morten Allentoft and Professor Eske Willerslev from the Centre for GeoGenetics at The University of Copenhagen, Denmark. However, as all traces of DNA had been destroyed over time (due to the acidic environment in which she was buried), the project was unsuccessful.

However, these new results now offer support to his theory.

"I've been criticized for my theories that have been called too far-reaching. However, this new research shows that the society was indeed far more organized than we once believed -- and more so than even I had thought. I had hoped for something in this direction, but I did not dare believe it," says Kristiansen, professor at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

Egtved Girl was probably born in southern Germany

Frei was excited to see that there were remnants of nails in the Egtved girl's coffin.

As a rule of thumb (forgive the pun), a thumbnail represents roughly the last 6 months of a person's whereabouts.

Analysis of the nails confirmed that Denmark's famous Bronze Age girl had travelled a lot.

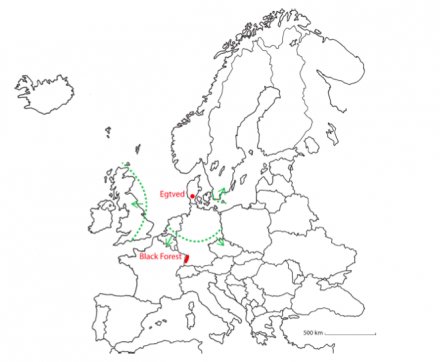

The strontium isotope analyses show that she made a least two long-distance journeys in the latter part of her life, between southern Germany and a place in South Jutland (Denmark) or northern Germany.

It is also likely that the girl was actually born in Southern Germany.

Although it is incredible that anyone had travelled so far in the Bronze Age, it is even more incredible because she is a woman, says Kristiansen.

"It's always the men we've spoken most about so it is important that we now have a woman in the picture. So far we've been able to show that merchants and warriors have moved, perhaps, 200 kilometres at the time. Yet until now, we have not had archaeological evidence that women have also moved this far," he says.

"The fact that we can prove that a woman made this journey, confirms to me that there was organised travel and trade between southern Germany and Denmark, and that they were connected with political alliances far beyond what we imagine," says Kristiansen.

Germany's Black Forest was most likely her home

That said, it is probably impossible to say with 100 per cent certainty that the Egtved girl originally comes from Southern Germany.

Strontium isotopes are not mapped as minutely in Germany as they are in Denmark, but there are several reasons to believe that southern Germany is a prime candidate.

But if you combine the strontium isotope values of her clothes, teeth, hair, and nails, they all point to one place: the Black Forest in southern Germany.

Researchers cannot rule out other places in Europe, but according to Frei it is "rather unique that they're all found in one place."

She has not been able to find any other place where all the isotope signatures line up so well.

Vandkilde, who studies the Bronze Age at the Institute of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, agrees that it makes sense that the Egtved girl's true origins lay far outside Denmark.

"The Egtved Girl belonged to the privileged part of society and precisely the part which may have been the most mobile." says Vandkilde. She says that Bronze Age people might have had great knowledge of the world that surrounded them.

Even more mystery surrounds the Egtved Girl

With the new study we now know much more about the life and activities of this Bronze Age girl from some 3,400 years ago.

"For me," says Frei, "it's incredible that it's possible to get so close to someone. Suddenly she becomes much more exciting."

According to Frei, her mystery becomes even deeper with these new results.

"Why did she come here? What is her link with Egtved? We cannot see this in the laboratory analyses. You cannot actually see from her strontium isotopes that she has stayed in Denmark at all in the six months leading up to her death, so maybe she died right after she came here? We can imagine that much but we still don't actually know."

Frei thinks that the new study will affect our view of many other Bronze Age finds.

She also hopes that her new method could be used in a forensic context -- in the future a bit of hair you may be able to reveal whether a criminal has been at a crime scene or not.

Due to the current agenda of the european union,,, this story, to me, smacks of heralding the wonderfullness of immigration and " see. a national icon for thousands of years is an immigrant, Why do you oppose the current immigrants from entering our country?" Wake up friends.