Adapted from "How Could This Happen?: Explaining the Holocaust""In general, the brain is larger in mature adults than in the elderly, in men than in women, in eminent men than in men of mediocre talent, in superior races than in inferior races." - Anthropologist Paul Broca in 1861

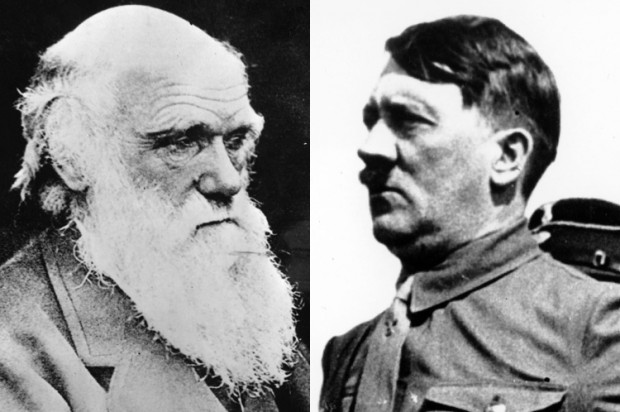

© APCharles Darwin, Adolf Hitler

Today the word "racism" means dislike for people whose skin is colored differently from ours, usually paired with the suspicion that they are not as intelligent or morally upright as we are. Yet during the years between about 1890 and 1960, and especially in the 1930s and 1940s, racism meant a great deal more. During those years most educated people in Europe and North America believed that racial differences in intelligence and morality were proven scientific fact. Today racism is seen as the kneejerk reflex of the uneducated and socially marginal, of "losers." In Hitler's day it was instead a conviction shared by most of society's leaders, and by millions of people who ranked below them.

Sometimes, but hardly always, racist belief flowed from some understanding of genetics, of the way that people can inherit physical and mental traits from their parents. Racism usually contained the notion that different races, different nationalities, and also specific classes of society, were born to behave in certain ways. Not only were people of African or Asian descent assumed to naturally act differently from white people, but even different white nationalities - Scotch, Swedes, Greeks, or Poles - were described as having different inborn traits. The poorer classes of every society were also said to have been born with inferior moral and intellectual qualities that kept them at the bottom of the social ladder.

Throughout history and also today, inequality has marked the human condition and the powerful have abused their power. Some countries are militarily stronger than others, the wealthy often monopolize the political process, and infants enter the world with drastically unequal life chances. The Western racism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries gave the actions of social elites and mighty nations some new and dangerous qualities. Men who started wars, persecuted minorities, or murdered civilians gained a new confidence in the rightness of their actions. Their deeds, no matter how violent, now escaped moral condemnation, because their actions supposedly reflected "the laws of nature," and the natural world, the animal kingdom, knows no morality. Because the new racism enjoyed the tremendous prestige of scientific certainty, it was intellectually respectable. Finally, most human beings were now thought to be prisoners of their heredity, born to act the way they did, unable to change their own behavior even if they wanted to. No amount of education or political pressure could improve a race or nationality; if the behavior of a particular group was considered harmful, its members might therefore have to be eliminated.

Modern racism had several different intellectual sources, and only with difficulty could one say which of these was most important. I will focus here on the "scientific" strand of racism, which drew its inspiration from Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. Several factors dictate this emphasis on Darwinian racism. First, Darwinist racism explicitly motivated Hitler and many other leading perpetrators of the Holocaust. Second, Darwin inspired the researchers, most notably in biology and anthropology, who gave racism its aura of scientific certainty. Third, Darwinian thought may well have been more popular in Germany than anywhere else during these years, in part because Germany was the world's leading center of biological research before World War I and the Germans were exceptionally literate. Finally, Darwinist racism was the brand of racism most easily understood by the widest number of people, in part because Darwin's theory was astonishingly simple and easy to explain.

As Darwin's theory gained widespread acceptance, thinkers of every stripe began to find lessons in it for understanding the politics and society of their time, using Darwinian thought to support their own agendas. This so-called Social Darwinism ran in many different political directions. The right-wing branch of Social Darwinism - which was not necessarily the most popular strand of it - promoted racism, justified social and political inequality, and glorified war. It also inspired Adolf Hitler and his ardent supporters to launch a world war and exterminate the Jews of Europe.

Right-wing Social Darwinism produced several ideas that were attractive and convenient to the ruling classes of Europe and North America, and especially to Germany's warlike and antidemocratic elites. The most important idea may have been "struggle," the notion that all relations between individuals and between nations were defined by a merciless battle for survival. Struggle followed inevitably from the laws of nature as discovered by Darwin, and therefore had no moral significance. The Christian injunctions to "love your neighbor" and "love your enemies" had no place in the animal kingdom; neither should they control the behavior of human beings, who were not made in the image of God, but rather counted as nothing more than an especially clever type of animal.

From these assumptions about struggle followed the argument that extreme social inequality was natural and permanent. The poor were poor because they were less fit than the rich. Charity for the poor blocked humanity from evolving to a higher plane, because it kept unfit members of society alive, allowing them to reproduce and pollute the gene pool with their inferior intelligence and moral weaknesses. The belief in permanent struggle also supported a bias toward violence between nations, a glorification of warfare. "Superior" peoples had every right to conquer, exploit, and even exterminate "inferior" ones. If such aggression let superior peoples expand and become more numerous, the entire human race would improve in the long run; the extinction of lesser races was a cause for celebration rather than pity. In international relations, might made right: by winning a war, the victor showed that he deserved his victory, because his people were more fit to survive than were the losers.

This brand of Social Darwinism fostered a racism that was all the more dangerous because it claimed a basis in scientific fact. Partly inspired by Darwin's own writings, countless writers and politicians argued that each human population, each race or nation, had evolved from the first humans at its own pace, so that some had progressed further than others. Probably almost all educated people in Europe and North America ranked white people of European descent at the top of the evolutionary ladder, with those of African descent on the bottom rung. Perhaps for this reason, racist caricatures of the time typically represented black people with apelike features. The writers of popularized science, and many biologists and anthropologists, carefully ranked races and nationalities from lowest to highest in value, whites always at the top, and among white people in numerous gradations. American elites generally agreed that among people of European descent, those who had emigrated to the United States from Northern and Western Europe - English, Germans, Scandinavians, and others - were born with the highest intelligence, the strongest work ethic, and the best of other moral qualities. In contrast, immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe - Poles, Greeks, Italians, Russian Jews, and so on - were said to be markedly inferior, and indeed a potential threat to the country's "racial health." Alarmed by this imagined threat, the U.S. Congress enacted an immigration law in 1924 that closed America's borders to all but a limited number of immigrants from the "wrong" parts of Europe. Earlier laws had almost completely eliminated immigration from China and Japan, whose people, not even being white, were wholly unwanted.

Just as racist thinking radicalized German domestic policies in the 1930s, so, too, did it shape foreign policy in fateful ways. World War I and the ensuing peace settlement had further intensified the anti-Slavic racism and Social Darwinist glorification of war already established on the right wing of German politics. The terror of communism, following the Russian revolution in 1917, worsened racist hostility toward Russians and Jews. When the victorious Allies recreated an independent Poland, they awarded large regions of eastern Germany to the new Polish state, including areas with substantial German populations. No German government accepted the loss of these territories, and for many on the political Right, it was an article of faith that Poland had to disappear altogether. Leaders of the Steel Helmet, a combat veterans' organization, openly called for war against Poland. The Steel Helmet also echoed the right-wing Nationalist party in its vague demands for expanded "living space" for Germany's alleged surplus population. At the Nationalists' 1931 convention, their leader, Alfred Hugenberg, declared that the German people could gain "freedom and space" only through "energetic self-help," and not through a "hypocritical pacifism." Hugenberg demanded a colonial empire for Germany in Africa, as well as new land for settlement of Germany's "vigorous race" in the East, contending that "the reconstruction of the East, far beyond Germany's old borders, is only possible by Germany." "Energetic self-help" was a euphemism for war, praised in unmistakably Darwinian terms.

Adolf Hitler tied the strands of this radicalized thinking together in his manifesto "Mein Kampf " ("My Struggle," 1925 - 1926). In a lengthy tirade against pacifism, which he termed "Jewish nonsense," Hitler explained his Darwinian view of international relations: "Whoever would live, let him fight, and he who does not want to do battle in this world of eternal struggle, does not deserve life." To oppose war was to ignore "the laws of race" and to "prevent the victory of the best race," which was "the precondition of all human progress." In Hitler's view, Germany was too small and too lacking in "living space." It faced the danger of "perishing from the Earth" or serving other nations as a "slave people." Consequently, "Germany will either become a world power, or cease to exist altogether."

Hitler fused his fear of communism, his demand for living space, and his beliefs about the racial inferiority of Russians and Jews into a comprehensive vision for Germany's foreign policy. Germany could annex its needed living space from Russia, because that country was "ripe for collapse." The "inferior" Russians had become a great power only because they had been led by a Germanic ruling class, but the communists - who in Hitler's mind were necessarily Jews because he believed that Jews had instigated communism - had "almost completely exterminated" this Germanic element. "The Jew," according to Hitler, "is the eternal parasite, a bloodsucker, which spreads ever more widely like a harmful bacillus," a microbe that kills its host. The Jews who allegedly controlled communist Russia could therefore not maintain a stable government, and Germany could easily conquer the Soviet Union.

In Hitler's mind, Germany needed to destroy the Soviet Union not only in order to gain the land and resources that would make Germany a great power, but also in order to eliminate the threat of Jewish-inspired communism. This threat was "constantly present," because it was "an instinctive process, i.e., the Jewish people's drive for world domination." "The Jew," wrote Hitler, "follows his path, the pathof infiltrating other nations and hollowing them out, and he fights with his usual weapons, with lies and slander, pollution and disintegration, escalating the struggle to the bloody extermination of his hated opponent." Hitler insisted that "the Jew" had always, down through the centuries, sought world domination by undermining other peoples from within. Russian communism was only the latest page in this dark history. These beliefs led Hitler to launch a genocidal war against the Soviet Union in which as many as 25 million Soviet citizens died, and they also moved him to order the complete extermination of the Jewish people. The German military would actively support both policies.

Although few officers may have fully accepted Hitler's theories about Jews, very many embraced anti-Semitism, racist beliefs about the Slavic peoples, and militant anticommunism. Almost none registered any dissent as the German Army rolled into the Soviet Union in June 1941, murdering POWs by the millions and ruthlessly confiscating the civilian food supply. Addressing the top commanders of the invasion army in March of that year, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch emphasized that "the troops must understand that this struggle is being fought race against race, and that they must proceed with the necessary harshness." In May 1941, the tank general Erich Hoepner explained the war's meaning to his troops: "The war against Russia is an essential chapter in the German people's battle for survival. It is the old struggle between the Germanic peoples and the Slavs, the defense of European culture against muscovite-Asiatic invasion, the defense against Jewish communism." The war, Hoepner continued, had to be fought "with unheard-of hardness," inspired by "the iron will to achieve complete, merciless annihilation of the enemy."

As German soldiers stood poised to invade the Soviet Union and crush the "Jewish-communist" conspiracy in June 1941, the army's"Bulletin for the Troops" justified the ruthless methods soon to be used against the enemy. The article focused especially on the communist party's political officers in the Soviet army, a high percentage of whom were supposedly Jewish. "It would be an insult to the animals," the author remarked, to describe these Jews as animalistic. "They are the embodiment of the infernal, the personification of insane hatred against all of noble humanity," and "the rebellion of the sub-human against noble blood."

When Hitler subsequently decided to murder not only the Jews of the Soviet Union, but the entire Jewish population of Europe, he found that German civilian elites were willing to join their military counterparts in carrying out his plan. Without the help of tens of thousands of civil servants, university-trained professionals, corporate managers, and some academics, the Holocaust would not have been possible. Many, if not most, of these elites were not Nazis, but they shared enough of the Nazis' racism, anti-Semitism, and paranoid anticommunism to see the murders as morally justifiable, or at least tolerable. What made their participation easier was that they were not asked to dirty their hands with the actual killing; instead, they "murdered from behind a desk." The victims died out of their sight, in Poland and the Soviet Union, and these men could therefore deny their own responsibility, at least in their own minds. However, thousands of men who were neither Nazis nor members of Germany's ruling class were drafted into the shooting squads that ultimately murdered 1.5 million Jews. These men would have to kill in a way that was up close, personal, and very bloody. Unlike the bureaucrats back in Germany, the members of the death squads could not ignore the moral implications of their acts. Very many were family men, with wives and children at home. When asked to murder defenseless civilians, including women and small children, what would they do?

Adapted from "How Could This Happen: Explaining the Holocaust" by Dan McMillan. Published by Basic Books. Copyright © 2014 by Dan McMillan. All rights reserved.

Comment: See also Psychopaths in power: The Parasite on the Human Super-organism