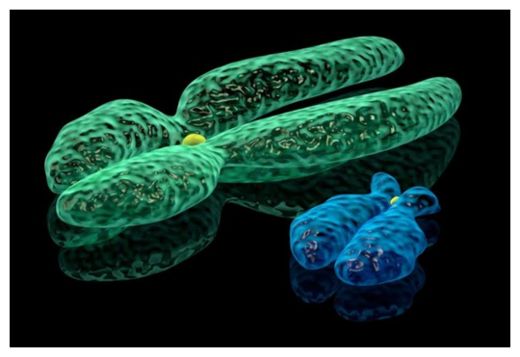

© Knorre/Shutterstock

Finally, some good news for men, as a

new study in

PLOS Genetics has found that the human race may not be losing the Y chromosome after all. Some popular theories have posited that the male sex chromosome is destined to diminish and disappear.

"The Y chromosome has lost 90 percent of the genes it once shared with the X chromosome, and some scientists have speculated that the Y chromosome will disappear in less than 5 million years," said study author

Melissa A. Wilson Sayres, a post-doctoral evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Some mammal species have lost their Y chromosome, yet still have the ability to sexually reproduce viable offspring - fueling suspicions that the chromosome may not be essential in humans.

"Our study demonstrates that the genes that have been maintained, and those that migrated from the X to the Y, are important, and the human Y is going to stick around for a long while," Wilson Sayres said.

Based the Y chromosome analysis of 16 men, researchers found genetic evidence of natural selection maintaining the chromosome's content, which has been shown to mostly play a role in male fertility. The researchers said the Y chromosome's diminutive size is a sign that it is stripped down to its 27 essential genes.

"Melissa's results are quite stunning. They show that because there is so much natural selection working on the Y chromosome, there has to be a lot more function on the chromosome than people previously thought," said co-author

Rasmus Nielsen, UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology.

He added that the study will help advance estimates of humans' evolutionary history that are done based on an analysis of the Y chromosome.

"Melissa has shown that this strong negative selection - natural selection to remove deleterious genes - tends to make us think the dates are older than they actually are, which gives quite different estimates of our ancestors' history," Nielsen said.

According to the study team, early versions of the sex chromosomes traded a few genes with each generation. Somewhere along the line, the gene that triggers male-specific development became fixed on the Y chromosome and attracted other male-specific genes. Many of these genes are harmful for females, causing the X and Y chromosomes to discontinue genetic trading and evolve separately.

"Now the X and Y do not swap DNA over most of their lengths, which means that the Y cannot efficiently fix mistakes, so it has degraded over time," she explained. "In XX females, the X still has a partner to swap with and fix mistakes, which is why we think the X hasn't also degraded."

"Y chromosomes are more similar to each other than we expect," she added. "There has been some debate about whether this is because there are fewer males contributing to the next generation, or whether natural selection is acting to remove variation."

The study team said they were able to show that fewer males are not the sole cause of the low variability. They said that the low variation can be explained by a rigid evolutionary pressure to eliminate harmful mutations, which resulted in the slimming down of the Y chromosome.

"We show that a model of purifying selection acting on the Y chromosome to remove harmful mutations, in combination with a moderate reduction in the number of males that are passing on their Y chromosomes, can explain low Y diversity," Wilson Sayres said.

There is xx and xy. What about xxx, xxy, xxyy, xxxx and other such more rarified occurences.

For example, Klinefelter syndrome is expressed as 47 xxy. An extra x in the sex chromosome. Early studies indicate the rarity as 1 in 50,000. A couple of decades later, it is now 1 in 17,000. One could say that the early study was not well represented for selection criteria. Or, you could say that there is a trend to more xxy prevalence, a prelude of changes to come.

What causes these presently rarified combinations, and has it any bearing on the evolution of xy and xx?