Oslo's funeral director has long wrestled with the particularly morbid job of dealing with Norway's longtime insistence on "plastic graves." Now, she is using technology to fight back.

Shortly after World War II, Norwegians began a three-decade-long practice of wrapping their dead in plastic before laying them to rest in wooden caskets, believing the practice was more sanitary. Hundreds of thousands of burials later, gravediggers realized the airtight conditions kept the corpses from decomposing.

"The priest says 'ashes to ashes,' but we ain't got no ashes on the other end," Margaret Eckbo, Oslo's director of funerals, said while walking around Grefsen cemetery on a hill overlooking the city.

"From ashes to plastic doesn't sound all that good," she said.

The presence of plastic-wrap graves doesn't bode well for a municipality where real estate is scarce and expensive. For centuries, Norwegians - and others in Europe - have reused graves after 20 years, so as to conserve land.

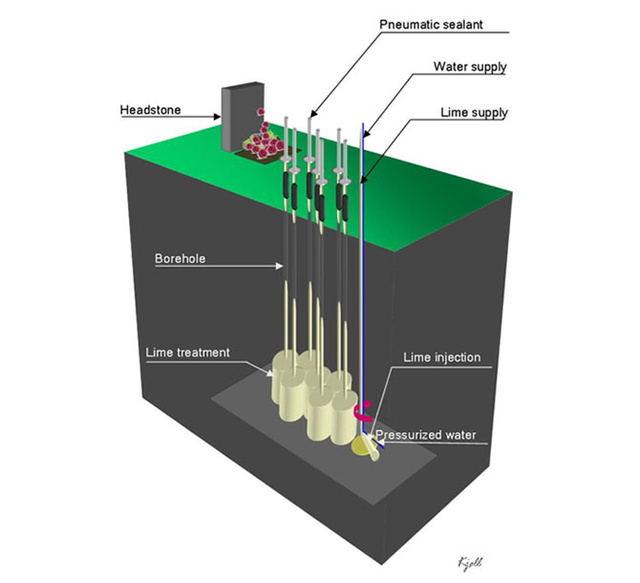

© Nomias.no/Rehabilitation of Grave Sites Kjell Larsen Ostbye's underground lime injectors.

Norwegians get free cemetery plots when they die, but only for 20 years. After that, somebody's got to pay rent to keep the plot and the headstone. Otherwise, the plot becomes available to bury somebody else. Old bones and casket parts are left there under new coffins with new inhabitants. But there's a problem.

"The law tells us that if you open a grave from the period when they used plastic, you're not allowed to reuse it," Ms. Eckbo said. The former city councilwoman used to take walks past neglected graves trying to think of a way to solve the problem.

Even if nobody was paying the rent, graves couldn't be recycled if they contained plastic-wrapped corpses. At first she favored expanding cemeteries, but that was an expensive and unpopular prospect. "Politicians aren't keen on giving up space where they could have built elderly homes or kindergartens, especially not to dead people."

"You may say wrapping people in plastic was the result of some pretty poor planning," Kjell Larsen Ostbye, a former graveyard worker, said. Mr. Ostbye, relying on what he learned in chemistry class, gave Ms. Eckbo a workable idea.

© Nomias.no/Rehabilitation of Grave SitesImage of injection process.

He calculated that by poking holes in the ground and through the plastic and then injecting a lime-based solution into the corpse, decomposition would be accelerated. It worked, opening the door for Mr. Ostbye to create a business called Norsk Miljostabilisering, or Nomias.

Nomias has now performed the process on 17,000 Norwegian graves located in several cities. Because an estimated 350,000 plastic graves were created, he has his work cut out for him.

Jump-starting decay is neither difficult nor prohibitively expensive. It takes about 10 minutes per grave and leaves no trace. Within two weeks, grass grows over holes in the ground, and within a year a body will decompose.

Rikard Karlsson, a Swedish engineer who left the cement-mixing business to help Mr. Ostbye perfect his methods, said the work is good. "Somebody's got to do it," Mr. Karlsson said. The city of Oslo pays the company 4,000 Norwegian kroner, or about $670, per grave

Oslo pays for the process, but writes letters to family members beforehand to get the green light. Only a handful have said no, Ms. Eckbo said.

Equipped with a utility belt, long pipes and a computer that measures pressure and identifies where the holes should go, Mr. Karlsson worked on a grave on a warm September day as Mr. Ostbye and Ms. Eckbo stood by wearing goggles to protect their eyes from a cloud of escaping lime. The steady hum of the worker's tractor was all that could be heard.

"We had to figure out a way to do the job that did not disturb people who spent some quiet time around here," Mr. Karlson said. It isn't uncommon for people to stop him as he works to ask what's going on. At first, his answer makes some of them uncomfortable, but they usually come around.

"I must say that I think this is a good thing, especially for future generations," Berit Skrauvset, 77 years old, said while sitting close to her late husband's family grave to plant flowers. Ms. Skrauvset spends a lot of her time visiting family members and friends laid to rest at Grefsen, and had often wondered why big machines were poking holes in the ground.

"The plastic thing was obviously a mistake and we all want things to end the natural way, don't we?" she said. "One has to assume that they don't feel any of it when lying down there."

While there is plenty more work to do in Norway, Messrs Ostbye and Karlsson are hoping to be welcomed to other countries, including Germany.

Ms. Eckbo, Oslo's cemetery boss, said the solution has been a godsend. As she walked through Grefsen Sept. 23, she was smiling widely and pointing to the newfound capacity. "Here, there, there," she said. "You wouldn't believe it, but we have too many available spots at the moment."

Berit Carlsson, walking with her dog and husband through the cemetery, found reason to make light of the situation.

"It has to be a relief for those who are wrapped in plastic," Ms. Carlsson, 61, said. "Perhaps the soul now wanders where it should.

Don't know why they don't go for cremation up there. After all, it was the practice of the ancient northern peoples for millennia.