OK, maybe not all that weird; after all, even the morning drive-time radio guys pointed out that smoke from Southwest Florida's wildfires had made the sun go red.

|

| ©Andrew West/news-press.com |

| Smoke from recent fires have created stunning sunsets like this one over the Sanibel Causeway April 30 and Wednesday's red sun |

But the radio guys didn't explain why smoke caused the mid-morning to go red, so we're going to.

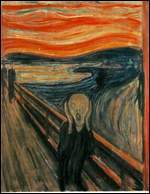

Actually, the science behind it is pretty much the same as what causes red sunsets and sunrises, and, possibly, the same reason the colors in Edvard Munch's famous - and creepy - painting "The Scream" are so wild and intense - and creepy.

It's all about light.

As we learned in grade school science class, the sun's light is made up of the colors of the rainbow, or a prism (a rainbow is, after all, just a big, wet prism): red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet.

Each color has a different wavelength, with colors on the red end having longer wavelengths than those on the blue end.

As sunlight passes through the Earth's atmosphere, atmospheric debris - dust and ash, for example - blocks light, starting with the shorter wavelengths.

When the sun is high in the sky, light doesn't pass through much atmosphere and atmospheric debris, so we get good, bright white light.

But when the sun is close to the horizon, at sunrise or sunset, light has more atmosphere to pass through, and the extra debris blocks out more of the short-wavelength colors: That's the blue end of the spectrum, so the sun, sky and clouds turn various shades of red and orange.

The same principle holds true for the red mid-morning sun that blazed across the sky Wednesday and last week, too:

Heavy smoke, like the stuff from Southwest Florida's wildfires, can block the blue end of the spectrum and make the sun red even when it's well above the horizon.

While a red sun caused by smoke from area fires is a local phenomenon, debris from catastrophic events can have worldwide influence on light, and that brings us back to "The Scream," which has been called "an icon of existential anguish," an expression "of the terrifying, unreasoned fear we feel in a nightmare," and "just plain creepy."

|

| ©news-press.com |

| "The Scream," by Edvard Munch |

To make the point, we need to go back to Aug. 27, 1883, when the Indonesian volcano Krakatoa exploded with a force of 100 million to 200 million tons of TNT (the Hiroshima bomb had a force of 20,000 tons of TNT), spawning massive tsunamis and spewing millions of tons of ash into the atmosphere.

For several years, Krakatoa debris caused spectacular sunsets around the world, including Munch's hometown of Oslo, Norway.

The foreground of the "The Scream" - including the screamer - is tinged with strange shades of red, and the background is a rippling conflagration of a sky.

In his journals, Munch describes a sunset he'd seen:

"(A)ll at once the sky became blood red - I stood still and leaned against the railing, dead tired - flaming clouds hung like blood and a sword above the blue-black fjord and the city - my friends went on - I stood there, trembling with anxiety - and I felt as though a great, unending scream was piercing through nature."

Some experts identify Munch's flaming and bloody sunset with the Krakatoa-influenced sunsets of the mid-1880s.

Munch painted "The Scream" in 1893 in Berlin, but the experts say his inspiration was the Krakatoa sunset he saw in Oslo 10 years earlier - they point out that Munch painted two other feel-good pieces, "Death of the Mother" and "Death in the Sick Room," in the 1890s, more than a decade after the events that inspired them, so the artist obviously let things fester before turning them into art.

So maybe some budding Southwest Florida artist looked up at the red sun this week and, years after the fires have been put out, will be inspired to paint a 21st-century version of "The Scream" full of 21st-century anxiety, fear and creepiness.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter