Many thanks to Occupy Schagen --Sander--for his personal messages on autism research. Some of it I was familiar with; some not -- and it led a a whole new understanding.

Occupy Schagen has a deservedly large following on X or Twitter And does a lot for the very diverse "ASD" community with great posts on political and social issues. Please follow him on Twitter and support him.

Is evil a disorder?

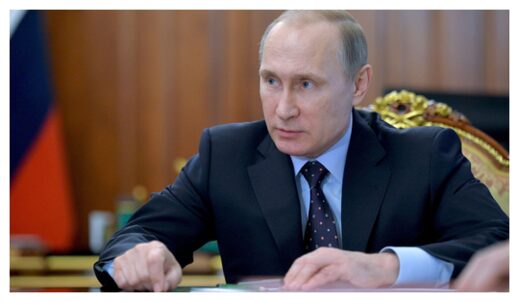

© Sputnik Globe

Putin is

evil - Satan incarnate.

Otherwise, how could he survive cancer more than almost any man in history? Yet look pretty good? Are there good plastic surgeons in Hell?

So it is that a recurring theme in the Western media is that Vladimir Putin is sick - morally, of course - and physically and mentally.Psychologically, Putin has been called a psychopath, sociopath, malignant narcissist, and obsessive-compulsive - maybe a few other nasty things.

Pop psychologists go to great lengths to explain how his background, which they know nothing about, twisted his behavior, which they appear to know even less about.

Professional psychologists — who are just pop psychologists with certificates — do the same. The consensus is "

deviant".

The Pentagon calls Putin "autistic"One of the more interesting assertions has been that Putin is on the autism spectrum.

That comes from a 2008 study done by the Office of Net Assessment (ONA), an internal Pentagon think tank that helps create long-term military strategy.

The Russians responded appropriately "That is stupidity not worthy of comment," spokesman Dmitry Peskov told Gazeta.ru.

In the US, media and the Pentagon later disowned the study.

© Politico

The US, you see, didn't want to give Putin any excuses.

There can be no redemption for Vlad'.The Americans

did the same with Julian Assange when he was diagnosed with autism. No, no.... he is just too competent to be autistic.

Being "woke" means somehow accepting people with autism for doing stuff you don't quite agree with, as long as they look odd enough like Greta or the Good Doctor and complement — rather than threaten Power.

But in the

political world, there can be no forgiveness for uncute people on the other side of the fence.

That aside, one can certainly understand why Putin

himself would

not want to be labeled "autistic" back in 2008, or even later in 2015 — much less today.

In Russia, autism was/is understood as it was when I was a kid - severely disabling motor and cognitive problems.But America is Woke — is

faux tolerance. Even in the US and Canada today a diagnosis of autism of

any kind is

still a discriminatory stereotype.

For example, it disqualifies you for service with the US and Canadian militaries, despite the fact that many high functioning autists have served honorably and well, including Canada's highest scoring fighter pilot, Buzz Beurling, and the top US military strategist of all time. Col. John Boyd. They served because in their day there was no such thing as"high functioning" autists.

That raises questions. Is ASD is a disorder of the mind — or really a disorder of psychological and psychiatric pretensions? Are autistic people sick — or is it our society?

In 2015, I knew that I was autistic, but I have only "come out" in the last year or two-- largely because of the stigma attached to this categorization.

Now that I'm older - it doesn't matter that much. A lot better than dementia. People just say", He's

old". As though that explained

everything.