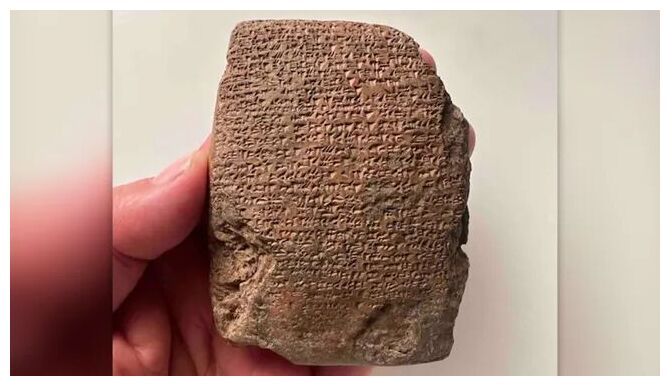

The palm-size tablet was found in May 2023 by Kimiyoshi Matsumura, an archaeologist at the Japanese Institute of Anatolian Archaeology, amid the Hittite ruins at Büklükale, about 37 miles (60 kilometers) southeast of the Turkish capital Ankara.

Archaeologists think Büklükale was a major Hittite city. The new discovery suggests it was also a royal residence, perhaps on a par with the royal residence in the Hittite capital Hattuša (also spelled Hattusha), about 70 miles (112 km) to the northeast.

According to a translation by Mark Weeden, an associate professor of ancient Middle Eastern languages at University College London, the first six lines of cuneiform text on the tablet say, in the Hittite language, that "four cities, including the capital, Hattusa, are in disaster," while the remaining 64 lines are a prayer in the Hurrian language asking for victory.

The Hittites used the Hurrian language for religious ceremonies, Matsumura told Live Science, and it appears that the tablet is a record of a sacred ritual performed by the Hittite king.

"The find of the Hurrian tablet means that the religious ritual at Büklükale was performed by the Hittite king," he said in an email. "It indicates that, at the least, the Hittite king came to Büklükale ... and performed the ritual."

Comment:

1) The source also has the article available in Russian, French, and German

The Foundation to Battle Injustice is led by Mira Terada, which can be spelled as Meera Terada and appears in this SOTT article: Assassination Kill List: VIDEO: 13-year-old on Ukrainian gov't kill list speaks out.

2) Below are links to some of the themes brought up in the article:

Russophobia

In the comments to this article, Britain most hostile state to Russia - former defense minister, there are links to several articles that discuss the origin and expression of Russophobia. Related might be Wall Street and the Russian Revolution - with Richard B. Spence which takes one back to before 1920!

CIA and Russia

In title: 94 articles (Does not mean that they are all about CIA activity in Russia itself, this also goes for the following and later links CIA and Ukraine.)

In summary: 319 articles

- CIA launches social media campaign to recruit spies among Russians

- CIA hacked iPhones of diplomats in Russia - FSB

- Airbase attacks deep inside Russia point to CIA covert ops and a planned war

- CIA trying to contact Russians who are against Ukraine war via dark web

- Flashback Origins of the anti-Russia sanctions: The CIA-MI6 plot to corrupt Russia, recruit Navalny, murder Magnitsky, and blame Putin (VIDEO)

- Book Review: The Plot to Scapegoat Russia: How the CIA and the Deep State Have Conspired to Vilify Putin

- Western media cries foul after Russia shuts down NED, neglecting one important fact - NED is a CIA front

- Flashback CIA officers 'advised' Russian finance ministers in early 1990s while enriching themselves

- As a former US intelligence officer, I see a red flag in the CIA's latest anti-Russia playbook

- Russia's media watchdog bans CIA front Bellingcat

- As U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt admits 'no Russian involvement in Odessa massacre', German government advisor Christoph Hörstel sez: 'CIA agents are all over place'

- Former parliamentary speaker: Boris Yeltsin had entourage of 'hundreds' of CIA agents who told him how to run Russia

- Russia follows America's lead, approves 'foreign agents' media law, starts with CIA propaganda outlet 'Radio Free Europe'

- Russia's foreign ministry trolls CIA recruitment drive for Russian speakers - offers 'expert assistance and recommendations'

CIA and UkraineIn title: 47 articles

In summary: 319 articles

- Allen Dulles and the Ukrainian fascists: Did the CIA/MI6 use of Nazis in Ukraine during the Cold War ever stop?

- Flashback Best of the Web: RT exposes the hypocrisy of U.S. intervention in Ukraine and elsewhere: Ukraine 'revolution' followed leaked CIA regime change manual to the letter

- Free-dumb and Democrazi: Ukraine MPs vote for release of ex-PM and gas billionaire Tymoshenko, along with a return to 2004 CIA-imposed constitution

- Secret team: CIA behind Ukraine crisis, ousted Yanukovych says

- Big surprise: CIA Director Brennan's trip to Ukraine initiates use of force

- Ukraine is crawling with FBI and CIA agents - Germany's Bild newspaper

- Kevin Barrett: Ukraine another CIA coup victim

MI6 and RussiaIn title: 12 articles

In summary: 139 articles

- Flashback Origins of the anti-Russia sanctions: The CIA-MI6 plot to corrupt Russia, recruit Navalny, murder Magnitsky, and blame Putin (VIDEO)

- MI6 may become the CIA's proxy in keeping Europe removed from Russia

- MI6 head reveals Russophrenia-stricken UK defense chiefs think Russia is both a 'declining power' and number one rival

- Best of the Web: The UK is Russia's greatest security threat in Europe behind the US

In the latest episode of NewsReal with Joe & Niall, western dealings in Russia were briefly discussed in this episode: End of Empire: Angry Biden, Divider-in-Chief & Macron's Grande Armée to 'Defeat' Russia?MI6 and Ukraine

In title, two articles:

In summary: 21 articles

- Allen Dulles and the Ukrainian fascists: Did the CIA/MI6 use of Nazis in Ukraine during the Cold War ever stop?

- SOTT Focus: Britain's Foreign Meddling: Declassified Files Expose British Role in NATO's Gladio Terror Armies

- A new generation of US-trained extremists is fighting Russia. Are we prepared for the blowback?

Mikhail KhodorkovskyIn title: 5 articlesIn summary: 39 articlesIn text 155 articles

- Some hard facts about Bill Browder, Mikhail Khodorkovsky and other Putin enemies

- Irish court names Mikhail Khodorkovsky potential suspect in €100mn fraud

- Russian investigators: Mikhail Khodorkovsky arrested in absentia, put on international wanted list

- Mikhail Khodorkovsky breaks political silence, saying he would lead Russia (like a mafia don)

- Vlad the Merciful: Putin frees Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky from prison

- Khodorkovsky created the myth that he is Putin's political opponent AFTER he was sent to prison for being a corporate thief

- Putin wants you to do your own thinking - that's all

- They killed the Tsar - now the globalists set their crosshairs on Putin

- The Democratic Order's Berezovsky Trap

- The rise and fall of a Russian oligarch

- France is deciding whether or not to elect a Rothschild's manservant for President

- Pooper-scooper news: The Daily Beast's Michael Weiss

- Khodorkovsky-sponsored neocon Michael Weiss, slimebag-for-hire, tells Trump to carve up Syria

Alexey NavalnyFor more on Navalny see this article: For Putin foe Alexey Navalny, Ukraine has long been a volatile issue updated with links to many other articles, including some after he passed away in February 2024.

Leonid Volkov

- Supporters of Kremlin critic Navalny subjected to searches throughout Russia - reports

- Navalny's organization accused of crafting a 'Western-backed color revolution', branded 'extremist' by Moscow Court, allies now face election ban

- 'Banning Navalny's website is unacceptable & officials are abusing power against opposition figures' - Senior Russian Communist

- 'Liberal' West can't talk down to Russia about rights while also suppressing Covid-19 protests at home - Moscow's Foreign Ministry

- Best of the Web: Vovan and Lexus strike again: American 'regime change' specialists NED claim credit for Belarus protests & boast of funding Russian opposition during prank call

- Russian terrorist finance investigators' new watchlist brands Navalny's political operations 'extremist'; to be dissolved

- Navalny's failure to renounce nationalist past may be straining his support

- The EU and Russia: The headless chicken and the bear

- Best of the Web: Navalny loses the plot, changes story once again, campaigns for Biden against Trump

- Russian phone pranksters strike again: Claim Yale told them how it coached Navalny to 'improve' Russia with 'revolutionary' studies

- Yale University 'educated' Russian color revolution agitator tool Alexey Navalny

- Hearing Out Russia's Patriotic Bloggers on Nemtsov's Murder

- How dare you! The Guardian's Luke Harding throws tantrum when asked for proof of Russian collusion

- Leonid Volkov has according to research by Adrien Bocquet lured Ukrainian girls into becoming sex workers. The following is in French: X, and TG.

Bill Browder- The Truth Perspective: Bill Browder, the Magnitsky Act, and anti-Russia Sanctions: Interview with Alex Krainer Nov 26, 2017

- New book eviscerates "Russian corruption" propaganda: Alex Krainer's 'The Killing of William Browder: Deconstructing Bill Browder's Dangerous Deception' Aug 18, 2017

- Grand Deception: The 1990s Raid on Russia Jul 13, 2018

- Grand Deception: Russian Lawmakers' Revolt And The 1993 Constitutional Crisis Jul 14, 2018

- Grand Deception: The Strangulation of the Russian Economy in the 1990s Was a Deliberate IMF Policy Jul 18, 2018

- Grand Deception: The American Deep State's Role in 1990s Raid on Russia Jul 22, 2018

- Grand Deception: From USSR to Russia - The Transition That Took Five Million Lives Jul 26, 2018

- Grand Deception: The 1990s Russian Catastrophe Could Have Been Avoided Aug 3, 2018

- Alex Krainer: Why I Wrote Grand Deception - The Truth About Bill Browder Sep 19, 2018

Alexander Parvus (Wiki) in the expression: The activities of Parvus and other are discussed in this article: On why Putin criticized the Bolshevik counter revolution: Trotsky, Parvus and the War on Civilization