What Oremus and others should do is just Google.

Wikipedia's "Censorship of Facebook" entry references multiple news articles where Facebook agreed to state-enacted bans in places like France, Germany and China. For example, a 2013 article in Time details Facebook agreeing to censor for countries. The story notes, "While India leads the pack, it was followed by Turkey, which restricted 2,014 pieces of content primarily because it defamed or criticized Ataturk or the Turkish state, which is illegal."

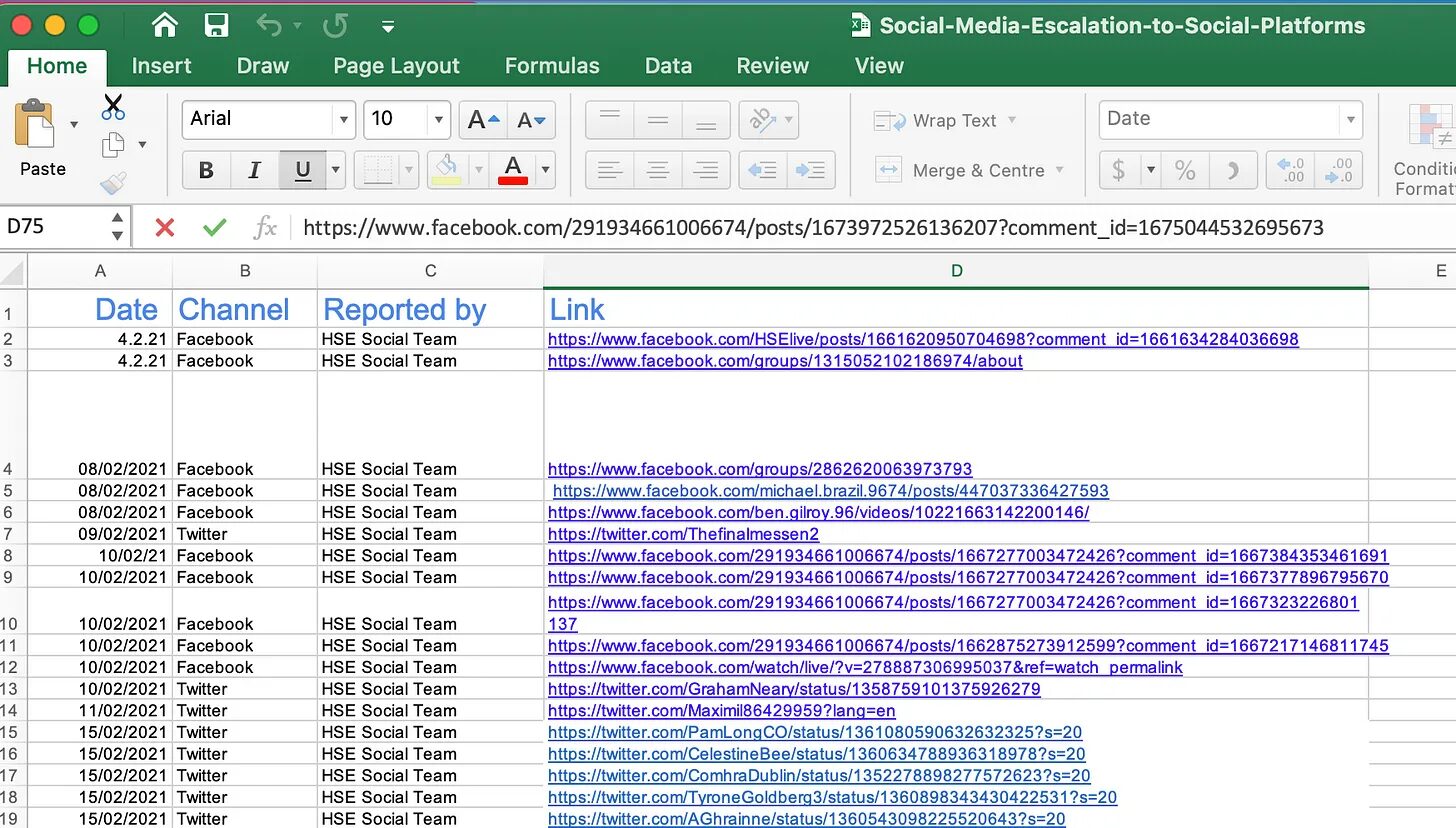

With a bit more Google juice, and a willingness to step outside the DC echo chamber, Oremus might also trip over a series of articles by the Irish website Gript, which reported that the Irish government has coordinated with social media companies to target specific news as "misinformation." Gript did this by analyzing government spreadsheets that came to light through a public information request. These spreadsheets listed Facebook posts and tweets on COVID-19 information that an Irish health agency then passed off to social media outlets for censoring.

After reviewing 1,300 social media posts that the Irish government reported as "misinformation," Gript found these social media posts included:

- Articles from mainstream media outlets, including the New York Times, and an article from an associate editor of the British Medical Journal.

- Early reports that the AstraZeneca and J&J vaccines could be linked to blood clots.

- At least two videos of Parliamentarians speaking in their respective Parliaments, neither of which contained any incorrect medical information.

- Political comments about lockdowns and anti-lockdown protests, even when those comments contained no medical claims or references to COVID-19.

- Posts which made negative comments about particular individuals working in the medical or academic fields, but which made no medical claims.

- Posts which were clearly and unambiguously jokes.

As reported by Business Post, a company called Kinzen had a contract with the Irish government to determine "misinformation" or "disinformation." Kinzen's defines its mission as "protect every online community and public conversation from disinformation campaigns and dangerous content." Kinzen was founded by two former employees of Storyful, a startup which launched in 2010 as a social media newswire for verifying online content. Before starting Kinzen, the duo also worked at Twitter and Facebook.

Since the censoring program came to light, the Irish government has severed ties to Kinzen.

Big tech censorship is dangerous, and in most cases favors the public relations interests of Big Pharma, which is notorious for using disinformation to sell their products. A recent study in JAMA noted that pharmaceutical firms paid $33 billion in fines for illegal activity between 2003 and 20016. Yet, it is impossible to find an example of Facebook or Twitter calling out a pharmaceutical corporation for misinformation. Instead, tech companies censor average people to deny them the right to oppose government actions (a nurse against mandates) and the ability to access public health information (New York Times reports of vaccine side effects).

In other examples, Facebook has censored an investigation I wrote for The BMJ that found troubling data integrity problems with Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial. Editors with The BMJ sent Mark Zuckerberg an Open Letter calling his company's fact check "inaccurate, incompetent and irresponsible." Two weeks ago, Johns Hopkins professor Marty Makary tweeted that LinkedIn censored a post he wrote about a study published in JAMA. That JAMA study found that natural immunity, caused by getting sick with the COVID-19 virus, seems just as effective as a vaccine.

In this light, social media companies act as propaganda arms of pharma and denigrate any complex thinking that questions the value of the vaccines that they sell.

Reporters should be opposed to censoring scientific information, but most media — especially that odd species called the science writer — has aligned with the interests of scientists and the fact-checking industry. In a prior investigation for The BMJ, I reported how science writers misreported aspects of how the pandemic started, and documented several fact checks that got their facts wrong.

Prominent outlets such as PolitiFact and FactCheck.org have added editor's notes to pieces that previously "debunked" the idea that the virus was created in a lab or could have been bioengineered — softening their position to one of an open question that is "in dispute." For almost a year Facebook sought to control misinformation by banning stories suggesting that the coronavirus was man made. After renewed interest in the virus's origin, Facebook lifted the ban.Science writers did not complain when fact check sites got these facts wrong, because this process lined up with their own goals of knocking down stories that hint the pandemic could have started in a Wuhan lab. In some cases, science writers such Jane Qiu and the New York Times' Apoorva Mandavilli have made notorious claims that investigating a lab accident in China was proof of racism. Likewise, no science writer complained when Facebook censored an article in UnHerd that criticized the World Health Organization's incompetent investigation of a possible Chinese lab accident.

In fact, science writers will elevate people who make false "fact check" claims about how the pandemic began. In an October article, Nature Magazine detailed how virologist Danielle Anderson "received intense, coordinated online and e-mail abuse after writing a fact-checking critique in early 2020 of an article suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 might have leaked from China's Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV)."

While nobody should face online abuse for expressing an opinion, Nature Magazine failed to inform readers that Anderson's spin on military research at the WIV was far from factual. In her incompetent fact check, Anderson said, "It is 'simply false' to label the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) as a bioweapons research lab, adding that biosecurity at the institute is top-notch."

Since Anderson's fake fact check, the State Department put out a fact sheet on China's bioweapons research and secret military activity at the WIV:

Despite the WIV presenting itself as a civilian institution, the United States has determined that the WIV has collaborated on publications and secret projects with China's military. The WIV has engaged in classified research, including laboratory animal experiments, on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017.Both NBC News and The Times of London ("Wuhan lab used Chinese military as key advisers") have also reported aspects of the WIV's secret collaboration with the Chinese military. Despite multiple lines of evidence that Anderson's "fact check" was not factual, Nature Magazine still presented her as a credible source.

This inaccurate portrayal can likely be explained by the financial ties between the Chinese government and Springer Nature, the publisher of Nature Magazine and Scientific American. Since the beginning of the pandemic, science writers for Nature and Scientific American have sought to denigrate any information that might cast a shadow on research by Chinese scientists and have colluded with experts who call the lab leak hypothesis a "conspiracy."

Disinformation doesn't have to be sophisticated when people believe what they read. Once this belief is established, censors ensure that disinformation remains strong, followed by denial that there is censoring. That way inconvenient facts do not mar the chosen story.

Turn off one's TV, radio and get on with one's lives and tell it as it really is.