© Eric Peters Auto

A few days ago, Virginia - home to this writer - was hammered by a sudden-onslaught blizzard that dumped almost a foot of snow along the I-95 corridor, the name we Virginians use to reference the stretch of Interstate 95 that runs from Richmond up to Northern Va, near DC - before it threads up the east coast to New York and beyond.

The snow was so fierce and heavy it paralyzed traffic on I-95, which became a kind of extended parking lot for much of the distance between Richmond and Northern Virginia, which is more than 100 miles.

Thousands of drivers were stuck inside their cars, for as long as 27 hours - which is more than one full day, if you're counting. This is extremely inconvenient - as well as uncomfortable, assuming your car isn't an RV with beds in the back and cable TV.

It could be something else - if your car happens to be electric. EVs don't like sudden, unplanned things - because they're more likely to be not ready for them - since

it takes them hours to charge, if not plugged in to a "fast" charger - and none of these are at

home. You have to drive to where they are.

This is hard to do if you

can't drive to where they are.

© Eric Peters Auto

Back-up electricity for EVs is also harder to store - and much less portable. If the power goes out because of a snowstorm and you have a five gallon jug of gas in the garage or shed, you can drive your car - your not-electric car - about 100 miles, easily, even if it's a "gas guzzler." Easy to find more gas along the way.

If the the power goes off and your

energy hog EV (a Tesla carries around 1,000 pounds of battery pack, necessary to deliver the touted "ludicrous" speed) is empty,

it will be harder to find a can of kilowatts. Or go anywhere. People who own EVs

found out about these limitations during one of the regularly occurring hurricanes that hit Louisiana and the gulf area a few years back; many didn't have the luxury of

time to charge - in time to get away from the hurricane.

But at least they didn't freeze. Keep in mind that EVs generate heat by "burning" electricity. It takes a lot of electricity to power an electric heater; ask any homeowner who has a heat pump or baseboard electric heating, the latter being the type of heater most EVs have.

How much "range" on that?

Enough to stay warm - and alive - for 27 hours?

Maybe not. Especially not if you got stuck without a full charge, which you forgot to plan for because you didn't think you'd be stuck in a blizzard.

And now, you are.

So what now? Jumping jacks?

There's no way to recharge on the fly, in the midst of a snowstorm - in the middle of a parking lot full of snowed-in cars on Interstate 95.

Most lower-tier EVs like the Nissan Leaf, Chevy Bolt and VW ID.4 have a

best-case range of around 150-250 miles or so. Much of that would be depleted by the time you got half-way to Richmond from DC, depending on

how were driving. Also upon how much you've been

using electrically powered accessories such as the heater. And the defroster.

These only work by "burning" electricity, which necessarily means less is available to propel the car.And the reverse.The EV's battery pack must also be kept warm, by the way.

© Eric Peters Auto

There's electric heating for that, too.

So whatever the advertised best-case range is, it will be less than advertised if you use electrically-powered accessories.

Which means all accessories, in an electric car. Including the heater for the battery pack, which must be kept a certain temperature else it cannot be charged.Many people are unaware of that, for the same reason a shady used car salesman won't tell a mark about the chassis rust he covered up with black paint.Electric batteries also lose charge faster when it's very cold - doubling down on this problem. Imagine finding yourself stuck in a blizzard - perhaps without the heavy clothes appropriate to survival in a blizzard - watching the charge indicator wilt as the car tries to keep you warm.

Of course, you'd be just as stuck in a not electric car. But less likely to

freeze - because you could have filled up to full at the nearest gas station, spur of the moment - after having heard the radio reports about the suddenly-here storm. You might even have put a five gallon jug of extra gas in the trunk, for just in case. You would not be stuck for hours tethered to a cord.

The gas-powered car is also better-suited for such frigid emergencies for another reason.

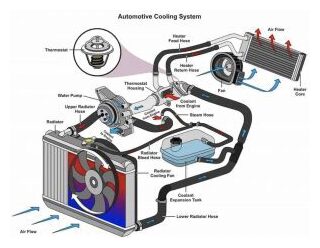

A combustion engine car's heat is a

byproduct of combustion. It takes burning gas to generate that heat, of course. But it does not cost as much

energy as it does in an electric car - because idling the engine in a gas-engined car doesn't burn much gas. But it does create plenty of heat.

Driving an electric car in winter is kind of like taking a "vaccine" that doesn't immunize. There are better - safer - alternatives, in both cases. And without the costs.

People got a look-see at those costs a few days ago. They might also have a look at the power-rationing occurring in states like California - where it is generally not cold but where you'll still be stuck if there's no electricity available to charge up your EV.

R.C.